A Lost Son of Texas

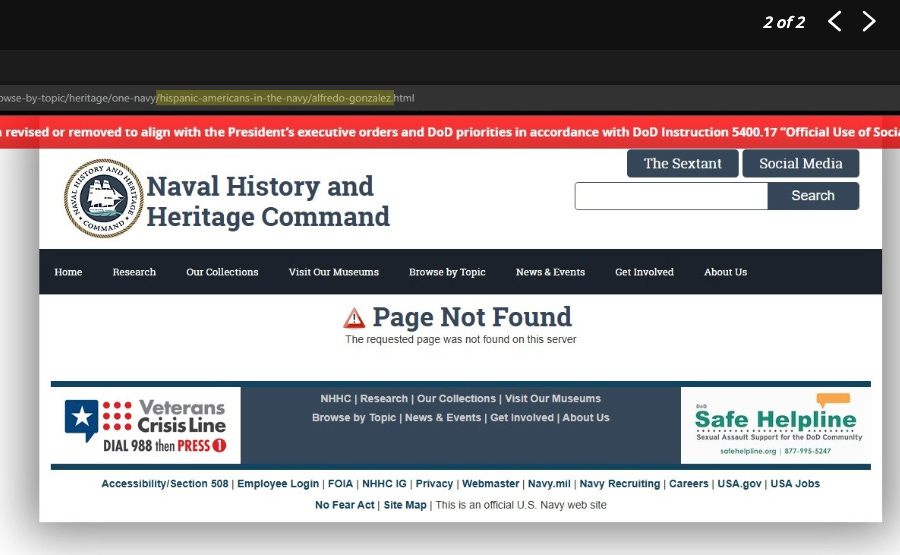

Freddy’s mother died last August at the age of 94. Were she still with us, she’d have another battle on her hands because The Medal of Honor recipient’s name, photo, and story have been taken down from Pentagon and Department of Defense and the Naval History and Heritage Command web sites.

“Some people wonder all their lives if they’ve made a difference. The Marines don’t have that problem.” — President Ronald Reagan

You have probably never heard his story, and if the present occupant of the White House gets his wish, you likely never will know about Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Gonzalez. But you need to read about the young man from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and the greatness, valor, and sacrifice that a disturbed president is trying to erase from U.S. history. Our collective shame ought to force a reckoning of remembrance and demand a correction of historical wrongs.

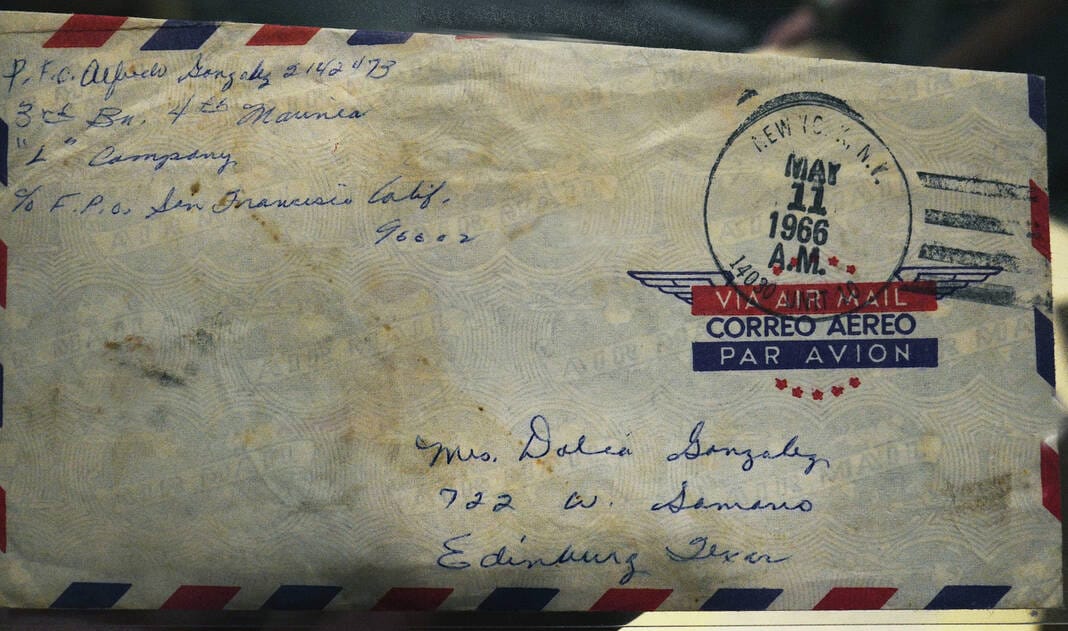

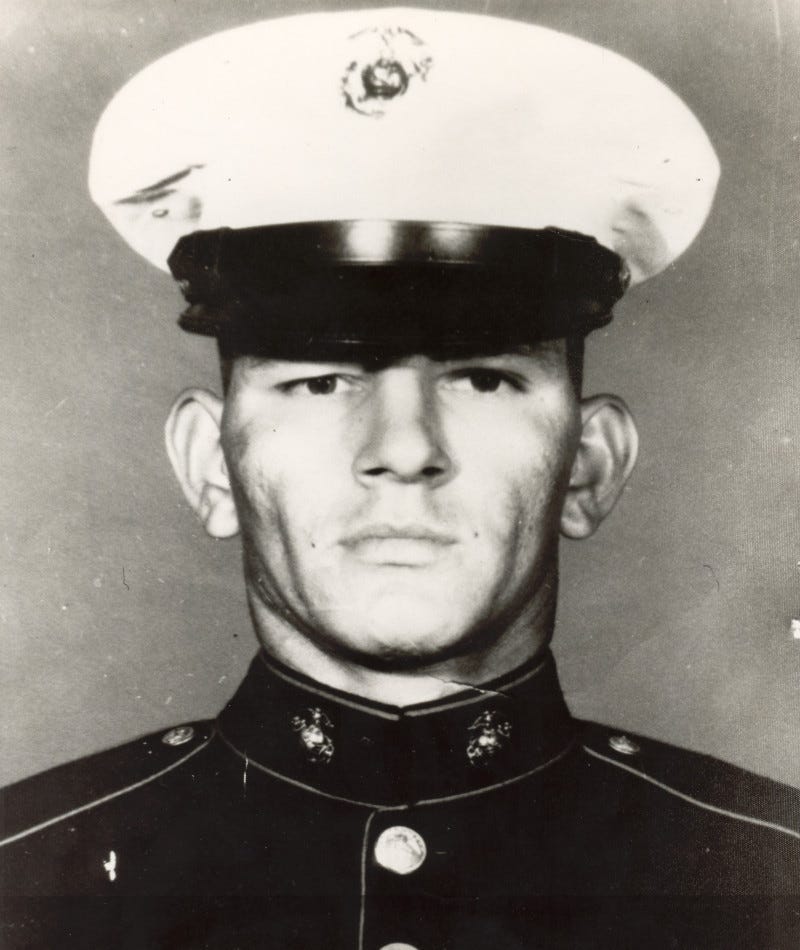

Freddy was raised by a single mother, Maria Dolia Gonzalez, after her husband, Andres Cantu, left his wife and only child. She worked the farm fields picking and hoeing crops, and as a waitress in a short order restaurant, to provide for her son. The financial hardships Dolia endured are probably what gave her diminutive son his values of perseverance and self-reliance. Regardless of the fact that he stood just 5’4” inches tall and weighed 135 pounds, Freddy became an All-District football player at Edinburg High School while also holding down after-school and summertime jobs to help supplement his mother’s modest income. The only time friends can remember him disobeying his mother’s wishes was when he decided to join the U.S. Marine Corps after finishing high school in 1965.

Freddy Gonzalez had endless reasons to surrender to anger. His community was influenced by systemic racism that was controlled by a predominantly white leadership and economic influence. Opportunities were limited for Hispanics on the border, regardless of how hard they worked or their level of education and intelligence. Freddy may have spent his entire life trying to prove himself an equal and to overcome the assumptions about him based upon his stature. Dolia had told an interviewer that she was watching a John Wayne movie with her son and he had leaned over and whispered into her ear, “Some day I’m going to be a Marine just like that.” Perhaps, his determination was just a form of overcompensation for his size.

Nobody knows what motivated Freddy Gonzalez, but he enlisted and went to Vietnam. Marines are, of course, always first in and last out of any conflict, which, his friends insisted, was a part of the intrigue for the Texan. While his mother spent parts of ‘66 and ‘67 at home, fretting, her son became a leader of men under fire, and returned to Edinburg unharmed after a tour of duty in the war zone. Freddy was not, however, ready to move onto the next part of his life, whatever that might be. He had just served his country honorably, the same nation back home that was discriminating against him and his mother because of their Mexican heritage. There were abundant reasons for him to take off his uniform and be done with military service. His reaction, instead, was the exact obverse of what might have been reasonably expected.

According to his close friend and fellow Marine J.J. Avila, Freddy was compelled to return to combat with a motivation to help. “He was on leave,” Avila told an interviewer in 2006, “And I remember he called me over to his house and said he had a serious dilemma. He had just gotten word that a platoon of men he had served with in Vietnam had been blown away in an ambush.” In Avila’s recall of his conversation with Gonzalez, he said Freddy was convinced that he could have kept those men alive had he been at the scene. “He had reason to be so confident. He saved many men through his coolness under fire, a calculating, rapid-fire courage, and a big-brother’s concern for his men. I told Freddy, do not go back. You’ve done your duty. He said he did not want to go back. He’d seen enough of the war, and he wanted to be close to home to take care of his mother. But the ambush really hit him hard. Finally, I knew it was no use. He’d made his mind up, and there was no changing it.

Unsurprisingly, Freddy volunteered for a second tour in Vietnam. When the Viet Cong launched their massive assault known as the Tet Offensive, he was 21-years-old and had been given command of the 3rd Platoon, Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, after its previous officer had been wounded and evacuated. The morning of February 4, 1968, Freddy and his men were approaching Hue, the old imperial capital of Vietnam. The VC and the North Vietnamese Army had five days earlier taken control of the city. Gonzalez and his men began to move toward the St. Jeanne d’ Arc School and Church, which was only about 100 yards distant and had been serving as a kind of fortress for the enemy. When one of his men was taken down by sniper fire, the sergeant ran out from behind a tank to rescue the fallen Marine private from a deadly position of exposure on the roadbed.

Gonzalez worked his way through the heavy tropical foliage of a ditch as his men raked a machine gunners’ nest with covering fire. When he approached the downed Marine, Freddy tossed two grenades into the VC position and stopped the attack before running onto the road, picking up his 170-pound comrade, throwing him over his shoulder, and racing back to safety. Gonzalez was also wounded and bleeding badly and the medic told him to get on a dust off helicopter for treatment. He refused, and continued to lead his men toward the VC that were protected by the bulwark of the church. Freddy saw that the building was heavily occupied and included an open courtyard, and that another platoon of Marines was advancing to get inside the structure. While the VC laid down withering fire, Gonzalez and his Marines took up positions to improve their chances of defeating the enemy. In the battle, a fellow officer described the Texan as a “one man army.”

The fighting inside the convent became room-to-room and Marines had to blast holes in the wall with explosives to make progress. Gonzalez, still suffering and bleeding from earlier wounds, got his hands on a few light anti-tank weapons known as M-72s, positioned himself on a second floor balcony, and began firing at enemy locations as he moved from window to window. According to a rifleman only a few feet from his sergeant, Freddy had taken out several enemy positions when a rocket launched in his direction hit him in the chest. Already credited with saving dozens of American Marines’ and soldiers’ lives, Gonzalez’ wounds were mortal. He survived the initial impact of the rocket, but the rifleman, Larry Lewis of Chattanooga, Tennessee, said his commanding officer’s heart stopped beating within minutes.

There were no bugles and drums for Sgt. Freddy Gonzalez when his body was returned to his hometown of Edinburg in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. In fact, the racial antipathy was still strong enough that attempts to publicly honor him were resisted with the power of prejudice from certain segments of the community. Dolia Gonzalez, however, was as determined as the son she had raised to manhood. She spoke constantly in public venues and to journalists in her efforts to ensure her son’s legacy was acknowledged and honored. Dolia went to the White House when her son was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1969 and then she returned home to continue her own battle to memorialize Freddy in his hometown.

Eventually, she won, although it took far too many years for the signs to be raised on an Edinburg main street named “Freddy Gonzalez Drive” and in 1975 for an elementary school to bear his name. His greatest honor, however, was becoming the namesake of one of the Navy’s most advanced and deadliest warships, an Arleigh Burke-class Aegis guided-missile destroyer, christened at Bath, Maine in February of 1995, and commissioned in October of 1996 in Corpus Christi. Home ported out of Norfolk, Virginia, the Gonzalez serves as part of the Atlantic fleet, Destroyer Squadron 22 ,and operates within Carrier Strike Group 10, and is still on watch thirty years after launch.

Freddy’s commanding officer in Vietnam, Marine Major General Ray Smith, who had witnessed the Texan’s heroics, instructed the sailors aboard the new ship of what was expected of them as they served the U.S. and the legacy of Sgt. Alfredo “Freddy” Gonzalez. “I said to the crew at the commissioning ceremonies as I passed the staff to the first officer of the watch and charged the crew to active duty status that Sergeant Gonzalez was a quiet, unassuming, modest man. But when the time came, he fought like hell. And this is a fighting ship, and the crew is obligated to Freddy that when it comes time to fight you will fight like hell too.”

Freddy’s mother, who spent most of her life fighting like hell for her son, died last August at the age of 94. Were she still with us, she’d have another battle on her hands because the current president’s executive orders have erased the historical record and memory of her son from government websites. The Medal of Honor recipient’s name, photo, and story have been taken down from Pentagon and Department of Defense and the Naval History and Heritage Command web sites because of a political decision by the White House to end all Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion references in government communications and institutions. It is, in the eyes of our current government, as if the hero never served, or even existed.

Freddy, as usual, is in exemplary company with other Americans whose character and heroics far exceed the petty policies of Washington’s leadership. As if to convince the public that white men were the “sole actors” in U.S. history, the racist algorithm of Trump has eliminated the biographies of baseball player Jackie Robinson along with content about Navajo Code Talkers from World War II, the first female Native American U.S. Marine and the first black Medal of Honor winner, a profile of Ira Hayes, a Gila River Indian who raised the American flag at Iwo Jima, stories about the Tuskegee Airmen, the courageous black pilots of the Second World War, and pages on Gen. Colin Powell, the first African-American head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A profile of Medgar Evers, a veteran of World War II and an assassinated leader of the American civil rights movement, was also edited out of existence from the Arlington National Cemetery website.

There are too many other DEI injustices and deletions to mention here, and a few have been restored after protest, but not Freddy Gonzalez’. Our tolerance of this criminal idiocy ought to have Americans asking themselves, “Is this really who we are?”

But, hell, maybe it’s who we always were.