A Port in History's Storm

The Titan submersible, carried past the narrows on a ship for a launch above the Titanic’s wreckage, now leaves its imprimatur of sadness on a people who have known too long and too well that the sea exacts a price for its glory and bounty, and preparation is the best hope for survival.

Below us, just before the dune line, wild Mustang horses were grazing on the tall grasses bending in a morning breeze off the Atlantic. We were with friends on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, standing on a deck with coffee and watching the sun rise out of the sea. The summer weather and location were idyllic, and then the phone rang.

“He’s gone now,” she cried. “I lost my, boy. Oh, I can’t believe it.”

“What happened? I don’t understand what you are saying.”

“It’s Noel. He’s drowned and gone. They couldn’t save him.”

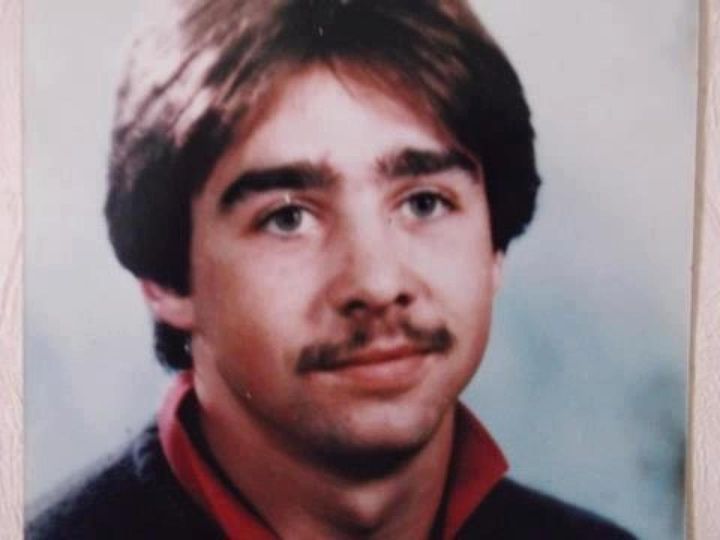

My cousin Bev had called from Newfoundland, crying, to tell us the horrible news that her only child had been swept into the Atlantic by a rogue wave. Noel, born on Christmas Day, had been sitting on a rocky ledge with two friends on a sunny August day in 1986 and had not moved quickly enough to avoid the water’s power. A trained lifeguard, he had saved several lives that summer of his eighteenth year, and knew to remove his shoes and heavy clothing for easier swimming as his friends ran for help a hundred yards distant at his grandfather’s house. Minutes later when they returned, Noel was gone, and a week long search by land, sea, and air, never found a trace of him or his struggle.

Noel grew up on the easternmost point of North America near the gun batteries overlooking St. John’s, Newfoundland’s harbor. His first love became the sea, the sounds and smells, rolling fog and rumbling ships shaking the windows of his room on winter mornings, the fish and fascinating creatures that lived in the salt water splashing along the rocky shoreline on his way to school. Noel had great expectations and wanted to become an oceanographer, which he intended to accomplish by getting a degree at McGill University in Montreal. He would have been the first of generations of our family to leave the island and get an education on the mainland.

My mother, too, had been raised among those Southside Hills, coming of age as history came pounding down the wharves outside her mother’s door. During the great wars of the previous century, St. John’s and its protected harbor served as a staging location for men and materiel bound for the overseas conflicts. My father’s orders as a soldier in the U.S. Army, to patrol the south side of the harbor as a military policeman during World War II, is how he met the girl who became his wife, and the mother of their six children. Pregnant and married at seventeen, young Elizabeth left for a sharecropper’s shack in the Mississippi Delta to wait for her husband’s return from the European Theater of combat. How could she know she was to become another storm tossed soul in the dramas constantly emerging on the rock where she was born?

Newfoundland’s geographic fate has kept it at the center of much of human history. Too often, the tragedies lead the island’s narrative, but there have also been great triumphs and advancements and the world has sometimes taken little note. Across the narrows from where my mother spent her youth, Cabot Tower sits atop Signal Hill, high above the ocean. The first trans-Atlantic wireless signal was received at the spot in 1901 by Guglielmo Marconi, sent via Morse Code from Cornwall, England. An infant industry of radio communications was given life on those heights. The ships sent searching for the OceanGate submersible passed within sight of the landmark as they departed St. John’s Harbor bound for the coordinates of the wreck of the Titanic with complex technology descended from that brief moment on a Newfoundland bluff.

Newfoundlanders are accustomed to their close community being filled with strangers from around the world, cruise ships and freighters, fishing boats, yachtsmen and wayfaring crews going down to the sea for adventure and income. Even though the Titanic’s tragedy was hundreds of miles off shore beyond the Grand Banks, the island became too closely associated with the sinking as a geographic marker, and later a staging point for scientists searching for the ship. The Titan submersible, carried past the narrows on a ship for a launch above the Titanic’s wreckage, now leaves its imprimatur of sadness on a people who have known too long and too well that the sea exacts a price for its glory and bounty, and preparation is the best hope for survival.

The captain of the Titanic, like the pilot and builder of the Titan, was brought to grief by hubris. The Titanic steamed almost full speed ahead into an ice field to make an impressive time in its first Atlantic crossing. Edward J. Smith, the skipper of the great ocean liner, wanted to improve on the overall time of another vessel of the White Star Line, so he sped into a sea of icebergs at 22 knots on a moonless night. The unsinkable ship was of a flawed design that did not seal off chambers of the hull from floods in separate sections. The Titan submersible, meanwhile, suffered the vanities of OceanGate developer Stockton Rush. His confidence in the integrity of his probe’s hull and comms systems despite criticisms by employees and external experts were certainly a part of the reason his vessel imploded and took his life and four others near the wreckage of the mythic ship. The Titanic is still counting casualties 111 years after she broke deep and took water.

I have wondered all week about the Newfoundlanders down on Water Street going about their business and watching the mainlanders scurrying around with their technology and submersibles and big ideas. If you were born on that rock, you learned quickly the goal is to stay on the surface of the water, not consciously go below for a petty notion like adventure, or even a grander one like science. Newfs generally don’t see the ocean as a place for capricious endeavors. They take their sustenance from the deep, and the best information to be acquired is not what wreckage looks like on the sea floor, but where are the fish and how can they be caught.

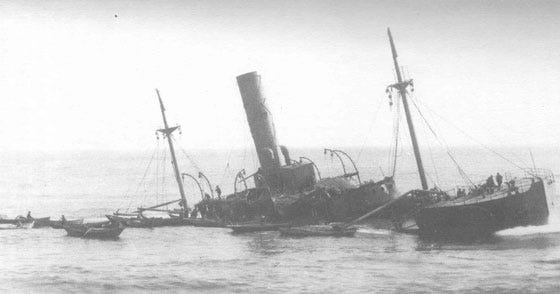

Six years after the Titanic went down, there was another profoundly disturbing ship wreck along the Newfoundland shore. The SS Florizel, which operated between St. John’s, Halifax, and New York, went aground at full speed near Horn Head Point after departing St. John’s with 78 passengers and 60 crew. Weather had turned bad and visibility was almost non-existent. The captain had been trying to get his boat through ice in the dark and had the mistaken conviction he had passed Cape Race, which would have cleared him to open water for Nova Scotia. Instead, he took her into the rocks. Only 44 of the 138 passengers and crew survived.

Rescue efforts in the icy sea were perilous. One of the men trying to pull survivors from the rocks and debris was George C. Hiscock, my grandfather, still a private in the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and home from the Great War. George C., mentioned in a book on the tragedy, “A Winter’s Tale: The Wreck of the Florizel,” had been carried overseas to battlefields on the Florizel with 540 other volunteers from his island home. Private Hiscock was described as trying to row a dory close to the rocks in the surging sea ice to reach survivors. He must have wondered, at least momentarily, about the maelstrom of tragedies drawing the Florizel into her dark fate. She had also been dispatched in an attempt to save men stranded on the ice during the “Great Newfoundland Sealing Disaster” of 1914, which cost the island of 250,000 persons a total of 251 lives. The cultural and emotional devastation had not ended, though.

As England’s oldest colony, Newfoundland took great pride in serving the crown. When World War I improbably began, the king sent out word to the island for volunteers to muster up and serve in the European trenches. My grandfather became part of a legendary group of young men known to history as the “First Five Hundred,” and the “Blue Puttees,” who signed up to leave home and fight an enemy they knew nothing about in an unknown land where they would likely die. The economy of the island was so poor there were insufficient funds to provide fully khaki uniforms and the puttees around their boot tops had to be made of denim, which gave them an iconic blue puttee look as they marched down to the docks while a band played a song of good cheer. The island, though, was about to sacrifice an entire generation of youthful intellect and energy as the Florizel shuddered into the open sea.

They went first to Gallipoli to relieve the Aussies, who were being slaughtered by “Johnny Turk.” The Newfoundland regiment arrived in time for winter and many of its troops froze to death before bullets could find them. Eventually, they were sent back to England to ready for an assault in the Somme River Valley in Northern France. They were ordered to dig in outside the village of Beaumont Hamel, near a ridge line occupied by the Kaiser’s soldiers and their machine guns. A sloping field of wire lay between British Expeditionary Force, which included the Newfoundlanders, Welsh Borderers, and Scottish Fusiliers, and when the orders came to go over the top, they were slaughtered. Of the 801 troops in my grandfather’s regiment, only 68 were able to muster the next morning on July 2, 2016. George C. Hiscock was one of the lucky ones, as am I, given the inescapable fact that my existence is a statistical anomaly of that war.

Grandfather had been “invalided out” of the service after being gassed at the Ypres Salient in France, and he was returned to his island home where everyone was stunned by the loss of so many young men, and the insensitivity of their commander who had told the media, “The attack failed only because dead men can advance no further.” In many ways, Newfoundland has not completely recovered from losing an entire generation that might have built a different future for the province. My grandfather, soon married and the father of four, tried being a merchant marine, and even went to the ice floes for the seal harvest. The wailing of baby seals with the blood and horror was intolerable after the carnage of France and he took a job in a pelting factory. Sharpening a knife on a wheel, his hand slipped and he cut his leg, which became infected. George C. Hiscock was dead of gangrene poisoning a week later at age 36, after surviving humanity’s deadliest days of combat at the Battle of the Somme where more than three million men fought and a million were either wounded or killed. Penicillin, which had been discovered and was beginning distribution, would have saved his life but had not yet reached the Newfoundland outports.

Both the association and proximity to these historic sadnesses has unfairly defined the island of Newfoundland. The Battle of Beaumont Hamel is appropriately memorialized but it has long been impossible to take a full measure of those lives not lived and what they might have meant. Another gathering of ships and technology and human resources on the docks at St. John’s Harbor to confront the second Titanic tragedy has also resulted in global media racing to the city to write another sad tale. CNN’s Anderson Cooper was jetted north from Atlanta to anchor his evening newscast from the waterfront and Newfoundland once more became a global dateline for incomprehensible horrors, which subsumed a narrative of the inspiring international human efforts at cooperation to save lives.

Not even Cooper was likely aware that he was standing where it is almost certain the European settlement of North America began when explorer Leif Erikson is believed to have found safe harbor at the site of St. John’s. He is thought to have sailed down from a Norse outpost called L’Anse aux Meadows, a permanent early community on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland, which served as a base for exploring rugged reaches of the continent a half millennium before the arrival of Columbus. International media also seemed equally oblivious when the great Russian and Japanese factory fishing ships had become so prolific at catching and processing cod on the Grand Banks that they had all but turned the Newfoundland staple into an endangered species. Bureaucratic nightmares developed before any Newfoundlander fisherman could get in his dory and go jig for a cod to feed his family because the government was trying to help the resource recover. Other countries had committed the crime of overfishing but the islanders were given the punishment.

When I think of my mother’s homeland down here in the Texas heat, I find my heart attuned to its people and hope that blood still runs in me. When the world was frightened by the events of September 11, 2001, tiny Gander Newfoundland gave back a belief in humanity. Thirty eight commercial passenger aircraft, inbound from overseas flights, were forced to land in Gander, a community of less than 10,000 souls. About 6500 people were stranded in a location that did not have hotels or restaurants to manage their numbers. No matter, word went out to “lend a hand, do what you can,” and homes were opened to strangers, schools and churches were turned into dormitories and cafeterias, and enduring friendships were formed.

A blog on the 9/11 Memorial website offers details:

“Area pharmacies filled prescriptions without cost, banks of free public telephones were installed so visitors could call home, and donations of toiletries, clothing, and food flowed in. Much of the food was stored at the Gander Community Centre’s ice rink, turning it into ‘the largest walk-in freezer in the country,’ according to Gander’s mayor, Claude Elliott.

“Once basic needs were met, the Newfoundlanders worked to entertain the visitors. They organized tours of the town, bowling matches, and concerts by local bands. Visitors also were introduced to regional cuisine, including stewed moose. When asked about their generosity, many residents responded that their efforts were not out of the ordinary. ‘For us, it was just every day,’ said Janice Goudie, a local newspaper reporter. ‘You don’t turn your backs on people in need.’”

The passengers did not forget the people of Gander, either. The crew and travelers on one flight established a scholarship for children in the area with $15,000 in donations, a total that has since grown to over a million dollars and provided assistance to more than 200 students. No one who has ever met a Newfoundlander on a street corner or in a pub was surprised by these developments. They would have only been shocked had things not transpired as they did in Gander, a community that serves as a last waypoint of overflight for outbound international planes from North America. Appropriately, perhaps, Newfoundland was also the departure point for the first non-stop Trans-Atlantic airplane flight by John Alcock and Arthur Brown, who endured 16 hours of mechanical and weather terrors in a refurbished World War I bomber. After leaving St. John’s, they finally landed nose first in a Galway, Ireland bog. Amelia Earhart, too, put the island in headlines when she flew out of Harbor Grace, Newfoundland, and became the first female to cross the Atlantic solo, touching down near Londonderry in Northern Island in 1932.

The Gander story was later turned into a wildly popular play entitled, “Come From Away,” the phrase Newfoundlanders use to describe outlanders either visiting or settling on their rock. The horror of 9/11 had been transformed into an inspirational tale by the kindnesses of Newfoundlanders for stranded strangers. My cousin, Mark Hiscock’s folk band, Shanneyganock, was asked to provide music for the opening night on Broadway. The play’s producer said the music for the show was inspired by Shanneyganock’s sound. Mark and his bandmates continue to travel the Maritimes and out to the provinces in the plains to sing for their homesick brethren. Happiness often has to be constructed from art when you are a Newfoundlander.

We can never seem, however, to avert our eyes from the tragedies. When I visited the battlefield of Beaumont Hamel in Northern France, I was stunned by the beauty and the silence as I tried to imagine what my grandfather and his comrades faced that morning. As the air slowly filled with birdsong, I walked among the trenches at the memorial site. Their edges were rounded by erosion and covered with soft green grasses. A few rusting artillery chassis were still pointed off to the German positions on Hawthorne Ridge and a giant caribou statue stood and faced defiantly in the same direction of the machine gun nests that had turned this grove to a killing field and a graveyard.

Sobbing as I walked past the graves of Welsh and Scots, I was approached by a docent from the museum. A young Newfoundlander serving in a summer job away from home, he asked if he might be of assistance. We talked, and I showed him the medal hanging around my neck given to me by my mother when I turned eighteen. My grandfather’s service medal on the front says, “For King and Empire, Services Rendered.” On the back, his name, “George C. Hiscock,” is etched with his enlistment number in the First Five Hundred, “N 297.” The docent held the medal gently in his palm and turned it over, studying it for some mystery he wanted solved. I told him it had never been off my neck, and never would be. He began sobbing without looking up, and softly excused himself from our conversation.

My mother’s life did not veer very far from the tragic Newfoundland script of her father’s. Though she lived a much longer time, she endured the kind of hardships that would have broken lesser spirits. After a few years of sharecropping cotton in the Mississippi bottomlands, my parents left for Michigan with my two sisters, looking for work in the booming industrial Midwest. Daddy got a job doing labor at the Buick Motor Division Plant and Ma carried burgers and open-faced sandwiches as a waitress in a short order restaurant. Her husband became violent, perhaps PTSD from the war compounding existing mental problems, and she eventually sought divorce after he was institutionalized a few times. Ma faltered, too, when brutal cancer rewrote her dreams. She lost the little coffee shop she’d owned for hardly a year, and the true love she had found with another man came to a painful end, but she never failed her six children, single-handedly making certain we knew we were loved while providing all she was able.

Ma spent some of her last years back on the island with her sister and two brothers and their families. She was there when I took my wife Mary Lou to Newfoundland and we ate giant lobsters, boiled in great cast iron pots, down by the ships, and we drove up into the Southside Hills to look out across that eternal expanse of water, still wondering about its glories and horrors. We also both got to know Noel a few months before he was reclaimed by the sea. Shortly after the call came to us on the North Carolina beach, we learned we would soon have a daughter and chose to name her Amanda Noelle, after the boy who loved the ocean. The timing gave us a comfort that our child was likely conceived during our visit to the island.

Most of the ships that sought to find the Titan submersible over the Titanic are leaving for their home ports, departing St. John’s, possibly to never return. TV crews and writers are packed up and on planes to other datelines, and, in some fashion, at least partly oblivious to where they have been and what they have reported. There was simply too much to absorb in too short a period of time, but what a story they have left untold. Newfoundland, meanwhile, will also resume its role of being a stage upon which great historical accomplishments are played out while also serving as the rock against which history painfully beats itself. She is as hard and cold as a Maritime winter and soft and sweet as an innocent child. No one who has been there ever forgets that island, and those of us whose lives and families are connected to the isolated rock, define ourselves with a simple and unfaltering statement of pride:

I am a Newfoundlander.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

The Boy Who Loved the Ocean

In Memoriam of Noel Hiscock, August 1986

by James C. Moore

You’re out there now on gabled winds

That shoulder gulls to finer heights

In every morning’s silvered mists

I’ll see your dance on water’s top

Where the ocean takes the early light.

You run the blue beyond my dreams

And own the sights I’ll never know.

Your storied home’s now distant shores,

The green of life between the rocks,

The mournful sound the foghorn blows.

I’ll hear your name on bounty’s wharves,

Your heart will furl their sails.

The stars that mark the way are you.

A sunrise calm will speak your love.

Your passage free their greatest tale.

I’ll climb for you the craggy peaks

And search beyond the shoreline’s clouds.

I’ll stride your race with aching breast

To give back your wins and keep your laugh,

The smiling way you made them proud.

I’ll take the pain god sends to me,

And pray one day I’ll understand:

Too much good he’d spent on you,

And in fairness called your spirit back

To spread more even all o’er the land.