American Memory

Within an hour, we went from curious explorers of history to mercenary capitalists, transporting alcohol in quantity across state lines w/o a license or a permit. In the dorm, we sold out in a few hours at $3 a can, $20 for a six-pack, and $90 for a case. I had never made more money in one day.

“One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.” - Wallace Stegner

I blame it on Spring. When the sun crosses the equator, reaching northward, the distractions of youth seem to multiply. Warming weather in the Midwest always affected my behavior. There was consistently an unsettling feeling that when the sun appeared, I was missing out on something, somewhere, a pickup baseball game, a hike, a gathering of friends, a motorcycle ride, or even a productive endeavor of some sort. Often, I was.

Spring was not even necessary for foolishness. One January day while in college, the forecast called for a warm Chinook wind to cross the lower peninsula and raise mid-winter temperatures to almost sixty degrees. There was no possible way I was going to make my classes the next morning. I mentioned the forecast to another motorcyclist and we both agreed to get our bikes out from under their tarps and ride north for an overnight campout on the Chippewa River.

The ride was warm and sunny and when we reached the river Steve and I put up our tents, built a fire, roasted hot dogs over the flames and wrapped potatoes in foil to lay against the coals. The night grew cool but was not uncomfortable. Unfortunately, when we awoke the snow was flying, thick flakes, heavy with moisture. The bikes were quickly loaded with our gear, and we went back south toward the university campus and our warm dormitory, more than two hours distant. The snow increased and the weather turned to a bit of a storm with accumulations in the breakdown lane. My jacket and gloves were minimal protection and I shivered uncontrollably, too cold to stop and seek shelter, deluding myself we could make it home. We had been betrayed by our youth and the Michigan weather.

We stumbled through a gauntlet of jokes from our fellow dorm residents as we went straight to our rooms. My Honda 450 had felt like it might go airborne at just forty miles an hour and, even though the road was not covered in snow, just the slightest turn felt perilous. The fact I was upright, and both my bike and I were unharmed, felt slightly miraculous.

“Hey, you interested in a trip?”

“Yeah, yeah, what’s the punchline?”

“No, serious, over spring break.”

The question came from Johnny O, a Detroiter whose father was a doctor. We had become friends over conversations about books and travel, and, like me, he loved history. I think the fact he came from money kept a distance between us because he frequently had weekend adventures in his new van with the camper and I was unable to afford participation, even on a minimalist basis.

“I’m not sure, Johnny. Kinda broke, as always. What did you have in mind?”

“I want to go drive along some of the overland trails the pioneers used,” he said. “There are supposedly still some original two-tracks across parts of the prairie, wagon ruts, ya know, and interesting graveyards and camping locations.”

“Yeah, you know I’d like to do that. But I may have to work through spring break. No money, as usual.”

“You don’t need any. I’ll get the gas and we can load up on food to avoid restaurants. It’ll be cheap, and I’ll cover any gaps.”

“I dunno, man, just seems……..”

“I’d consider it a great favor. I don’t want to go alone, and I’d enjoy your company. I know you like that stuff as much as I do.”

“Well, let me think about it, Johnny. But thanks, I’d sure love to but……..”

I knew, though, I was going to accept Johnny O’s offer and when classes were completed, we went west in his Chevy van out toward St. Louis and straight across Missouri to Kansas City. The first night we camped near Cahokia Mounds, a historic site of indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi River in Southwestern Illinois. Although we had never heard of the location’s history, we were still stunned to learn it had been a community of 20,000 people more than a thousand years before Europeans had landed in North America, and was the largest and most complex archaeological site north of Mexico’s great pre-Columbian cities.

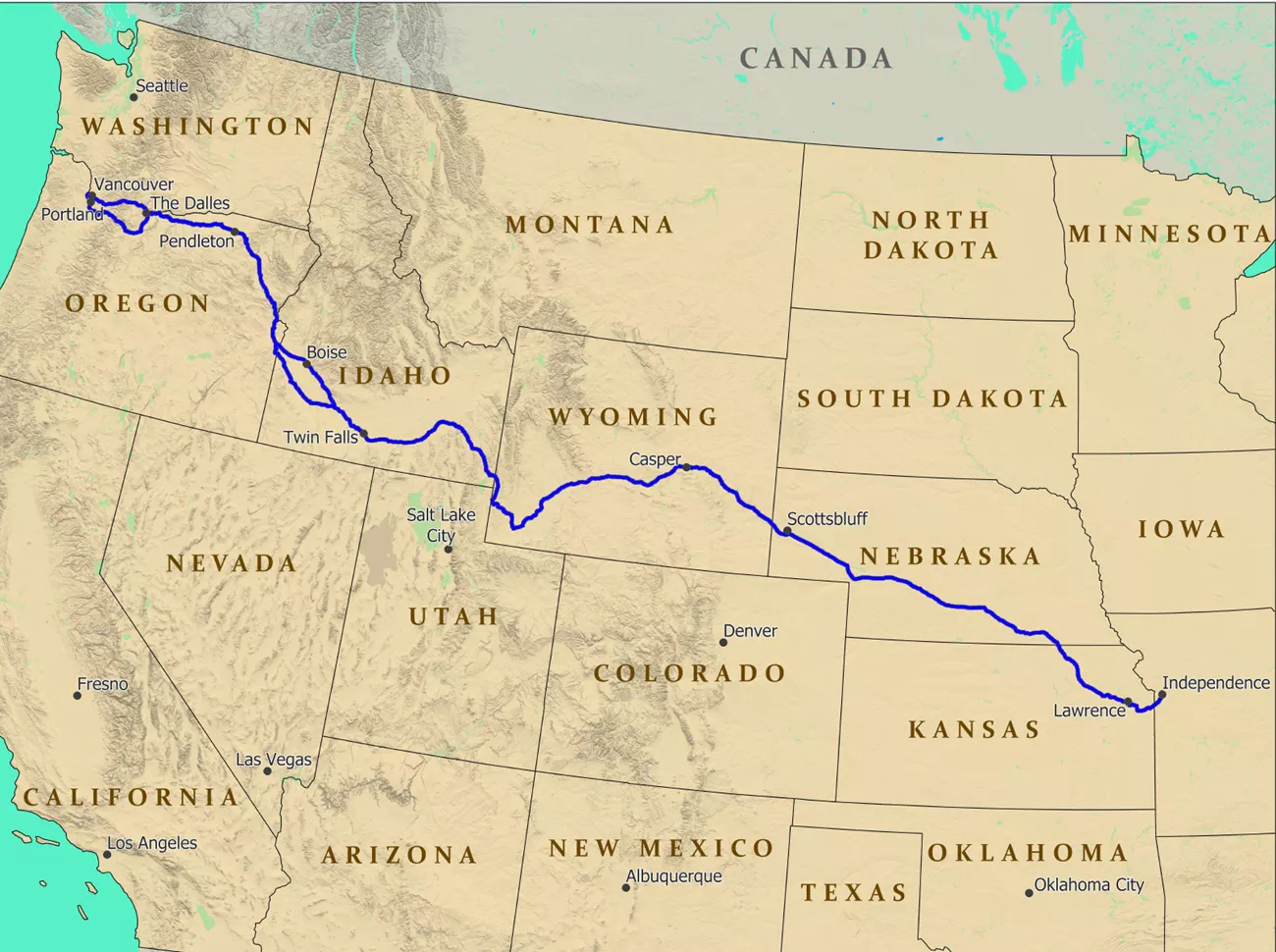

We ought to have lingered, and learned more, but we had only eight days before we needed to be back on campus, which sent us speeding across Missouri the next morning. I suggested we spend a few hours in Independence, but Johnny O wanted to get out into the countryside and find remnants of the Oregon Trail. Independence, though, had been the great gathering point for all the wagon trains preparing to move westward along the Oregon, Santa Fe, California, and Mormon Pioneer Trails. The notion of Manifest Destiny, a belief that white Americans of European descent were rightful heirs of the West, drove adventurers and dreamers out across the largely unknown territories.

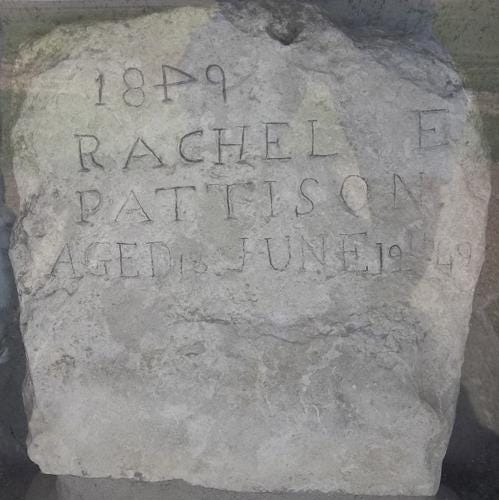

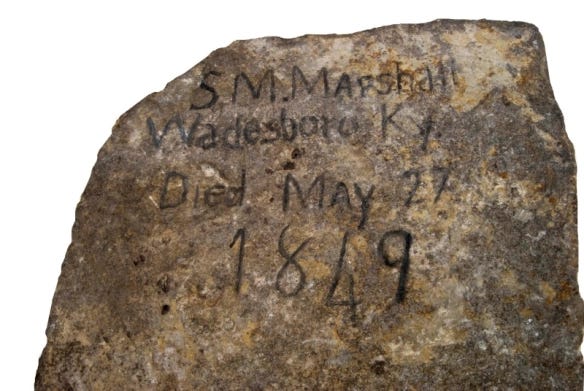

Near Lawrence, Kansas, we turned northwest, following the route of the wagon trains and the Forty Niners, who had risked their lives to get to California gold country. The Oregon Trail might be the longest graveyard in the world with an estimated 35,000 dead along its 2170-mile route, which averages out to a body buried every 80 yards. Depredations by Indian tribes were only one of the risks. They included cholera, influenza, dysentery, problem pregnancies, gangrene, and various accidents while trying to make passage through the wild country without effective medicines and doctors. Johnny O and I just wanted to see signs that people had passed this way and evidence of the trail’s existence.

“Hey, look!” I was excited, and pointed at a hand-painted, wooden sign with an arrow.

“Holy shit. I can’t believe it.”

“Well, we were told wagon ruts still existed. Pull over. Let’s look.”

The sign read, “Oregon Trail Wagon Ruts,” and directed our attention just beyond an open gate. Our western history professor at the university had told us ruts worn down by wagon wheels still existed in Kansas and Nebraska and that a few farmers had made personal efforts to preserve the heritage. The Oregon Trail beneath our feet that morning looked like two single track footpaths through a field.

“Can’t believe it.” Johnny O, sunk into a kind of personal wonder, stared at his feet. “We are standing on the Oregon Trail.”

“Yeah, pretty amazing. Look at those posts, too.”

“What about ‘em? Looks like he’s got this area fenced off with wire.”

“I suspect it’s probably because we are surrounded by native prairie grasses. Never been cut or plowed under.”

Johnny turned slowly around. “I’ll be damned. I think you’re right.”

“They were still crossing here less than a hundred years ago,” I said. “Feels pretty alive to me.”

Back in the van, we zigzagged state and county roads, several unpaved, while keeping a northwesterly direction toward Nebraska, where the Oregon Trail paralleled the Platte River. Johnny O, who appeared simultaneously smiling and contemplative, curled his shoulders around the steering wheel and rotated his head back and forth to take in the horizon. I thought we might get lucky and come across a cemetery that would be located where a wagon train spent the winter, but such a site was more likely further along the trail into Nebraska. We figured states might have made those gravesites into historic memorials, but we had been unable to find any guides or markers in our research.

There was no difficulty, it turned out, in finding cemeteries. We saw them situated near rural roads, unmarked, and others were fenced and gated, appearing to be family plots that dated back more than a century, souls that had forsaken the Oregon dream and settled on the high plains. I was drawn to small collections of stones that were surrounded by green shoots of Spring with land that had been plowed and seeded along the perimeters. The carvings were often primitive and had no names. An immeasurable sadness was communicated with the words, “Baby Boy, 1859.” The travelers probably wanted to remember but had no time to linger over names or be debilitated by emotion. Near the Nebraska line at the intersection of two county roads we spotted a field of stone, rocks that appeared to have been assembled over graves without concern for shape or alignment. We both were motionless in front of a stone with barely legible etchings that said, “3 babies, cholera, winter camp, 1856.”

“Okay, I’m done with this,” Johnny O said. “Let’s get up to the Platte and camp.”

“Agree. Sunny days aren’t meant for sad graveyards.”

“You can try all you want,” Johnny said as we crossed the state line, “but there’s just no way to get a sense of what those people faced.”

“Yeah, even traveling in groups with wagon trains, they were as alone as it is possible to be. No sign of other humans in any direction, and almost no ability to feel the distance they were covering. Horizon constantly moving, you scrape your knee falling, you could be dead in a week from gangrene. Almost amazing anyone made it to Oregon.”

“A game of numbers, I suppose. I think I read in one of my research papers that the estimate was 350,00 people came along the Oregon. I guess it was safer if you were in the later groups, eh?”

A few more hours passed as we made a couple dozen 90-degree turns working our way northwestward around all the 640 acre and square mile sections of land. Great green tractors constantly appeared on either side of the pavement, cutting turn rows for planting corn seed in a few weeks. Farmhouses and barns all stood back at a distance from the roadbeds as if no good could come of being close to passing traffic or improved surfaces for travel. Just south of Kearney, we crossed the Platte and stopped to take in the river course, defined in open stretches by cottonwoods leaning out over the water. I found it hard to believe the broad, shallow flow had played such a critical role in sustaining life and expanding the American frontier.

“Straight from the Rockies,” Johnny said. “I’m sure it looks a lot different in the high country but looks more like a sandbar in some places out here.”

“I’m pretty sure there were a lot of smiles when those beaten-up pioneers saw the trees and knew there was some kind of water ahead.”

“How far west are we gonna go?”

“Man, I’d love to see Independence Rock before we turned around,” I said. “You think it’s possible?”

“Don’t know. But let’s get going and see where we get to before dark.”

Interstate 80 followed the Platte as closely as the wagon train trails, but we went north and picked up U.S. 30, the old Lincoln Highway. Nebraska’s endlessness seemed more than an illusion as we hurried through the farm country. In Gothenberg, we could not resist stopping at a historic Pony Express station, now just an exit off a superhighway but once a remote outpost where riders carrying mail to California changed horses and raced onward. Almost exactly a decade later I would return to the location to film a feature report for the CBS Evening News, which was about a memorial re-running of the old mail route from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento.

The river forked east of North Platte into separate north and south flows, and we followed the southern course along Highway 30. The sun hung orange and large just above the sand hills to the west as we drove into Ogallala. In the gloaming with the faltering light on wooden storefronts, we felt like we had finally arrived in the American West, and Johnny parked his van beneath a large oak tree a few steps from a pub.

“Hey, look.” I pointed at a window where a neon sign flickered. “We must be in Coors country.”

“I guess we’ve stumbled into a good way to end this day,” Johnny O said.

We sat at the bar and ordered a pitcher of the legendary beer, and the bartender noticed our level of excitement.

“You are not from Nebraska or Colorado, I take it,” he said.

“No, Michigan,” Johnny said. “We can’t get this stuff back there.”

“Hell, ya can’t get it ten miles east of here on the Interstate,” he said. “We are pretty much the easternmost point for purchase of Coors. No distribution beyond Ogallala.”

“Seriously?” I took a big gulp from my frosted mug. “I’m not a big beer drinker but I love this stuff.”

“I hear that one a lot, too,” the bartender said. “Let me know if you need anything else.”

The establishment was mostly empty with a solo drinker at the other end of the bar and a middle-aged couple having an animated conversation at a nearby table. The floors were wooden, and baskets of peanuts were at every table, which meant shells were underneath every step a patron might take. Pictures of the local football team were on the wall behind the bar, and a few TVs fluttered fuzzy images from corner shelves.

“We aren’t gonna make Independence Rock, ya know?” Johnny tipped up his beer. “We’re kinda out of time.”

“Oh well, it’s just a big piece of geology with 5000 pioneers’ names scratched into eternal history, no big deal.’

“I’ve got something better.” Johnny O smiled and held up his beer.

“No offense, buddy, but a cold beer is nice but it’s not exactly an equal experience.”

“Agreed, but how much do you think we could get for a six pack of Coors back on campus in Michigan?”

“Holy crap. You’re right. We could pay for this entire trip and put a few hundred in each of our pockets.”

Johnny stood up, finished his beer, and put the mug on the bar. “Let’s go find a liquor store and load up with cases of Coors.”

In a little over an hour, we went from curious explorers of history to mercenary capitalists, transporting alcohol in large amounts across state lines without a license or a permit. The Interstate, which we had judiciously avoided in our meanderings, was now the precious infrastructure we needed to get our products to market. In the dorm, we sold out in a few hours at $3 dollars a can, $20 for a six pack, and $90 for a case. I had never made more money in one day. The eastern fascination with a beer that claimed to come from Rocky Mountain spring water probably existed because the beverage was only sold regionally in the Intermountain West. No other viable explanation existed.

Nothing can subdue my bright memories of those sunny days of my youth exploring the Oregon Trail’s history, but the trip concluded with a more comprehensive understanding of America than I ever expected to learn from following the path of pioneers. Their stories of triumph and tragedy were inspiring, fascinating almost beyond belief. I appreciated their motivation to take those risks, but I also finally realized that all American history is is somehow connected to making a dollar, and we often view everything else as just a distraction.

Which might help explain how we got into our current, unpleasant, predicament.