Black History Matters: Inspiration & Information in Medicine

Black History is not separate from American history. When children learn of the accomplishments of African Americans in many professions throughout history, they know that they can achieve their own dreams too.

Friends who knew us when my children were in elementary school knew that my son declared at age seven, he’d become a surgeon, and that my daughter loved money from the time she could form words. I supplemented their educations with stories of accomplished professionals who looked like them. They often surprised teachers and classmates in Texas with reports on historical contributions left out of their history books. I was fortunate. I had Black History in elementary school in the 60s, but I was in a bubble called, Berkeley. Today, book bans in Texas threaten to further hide significant truths and to present history from a white supremacist perspective. It is outrageous and, in my view, despicable. Black History is not separate from American history. This week, I un-hide those who contributed to the field of medicine.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

Surgeon

When the American Medical Association, (AMA), refused to allow Black doctors to join, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams co-founded the National Medical Association, (NMA) in 1895, a professional association for African Americans.

Dr. Williams grew up in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, the son of a biracial father, Scotch-Irish and African American, and an African American mother.

His father died when Dr. Williams was a child, and he was sent to apprentice with a shoemaker. He ran away to re-join his mother and set the foundation for his future. He eventually became fascinated with the work of a local physician and began an apprenticeship with Dr. Henry Palmer. Dr. Williams graduated from what is now Northwestern University Medical School in 1883 and opened his own practice serving Black and White patients.

Among his accomplishments are the founding of Provident Hospital, a welcoming place of residency training for African Americans. Staff and patients were integrated.

In 1893, he was appointed Surgeon-in-Chief for Freedman’s Hospital by President Grover Cleveland. He made improvements that reduced the hospital’s mortality rate. It would later become the Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

“A people who don’t make provision for their own sick and suffering are not worthy of civilization.”

–Daniel Hale Williams

Williams became one of the first surgeons to successfully perform open-heart surgery without modern surgical tools, the benefit of penicillin or a blood transfusion.

Through his study of germ transmission and prevention, his office practiced improved sterilization procedures for those times.

In 1913, Dr. Williams became the first African American to be inducted into the American College of Surgeons.

Dr. Percy Julian

Chemist & Entrepreneur

He pioneered the chemical synthesis or the development of medicinal drugs from plants, making them more affordable to reproduce. He was one of a handful of chemists at that time to enable the large-scale production of steroids from plant compounds.

Dr. Julian was born in Montgomery, Alabama, the grandson of enslaved people. Racial discrimination and an inadequate school system could’ve been barriers to his success, but his acceptance to DePauw University in Indiana provided him an opportunity to take high school and freshmen college courses at the same time. He played catch up and as a chemistry major, graduated valedictorian of his class in 1920.

Dr. Julian taught chemistry at Fisk, an Historically Black University, for two years before winning an Austin Fellowship to Harvard University, where he completed a master’s degree in organic chemistry. He continued graduate work at the University of Vienna through a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in 1929. He received a Ph.D. in chemistry and found greater acceptance among the intellectual community in Vienna than he experienced in the U.S.

His return to Howard was marred by faculty conflicts and a scandal as personal letters from Vienna were exposed. His former mentor sent him a much-need lifeline in the form of a teaching position at DePauw in organic chemistry.

At DePauw, Julian and his Viennese colleague, Josef Pikl, “accomplished the first total synthesis of physostigmine, the active principle of the Calabar bean, used since the end of the 19th century to treat glaucoma.” Physostigmine eases constriction to relieve pressure that if untreated, damages the retina and eventually causes blindness. The synthesis of physostigmine was published in the U.K. before Julian and Pikl, but theirs was the only product which proved successful.

Dr. Julian received more than 130 chemical patents and was the first African American chemist inducted into the National Academy of Sciences.

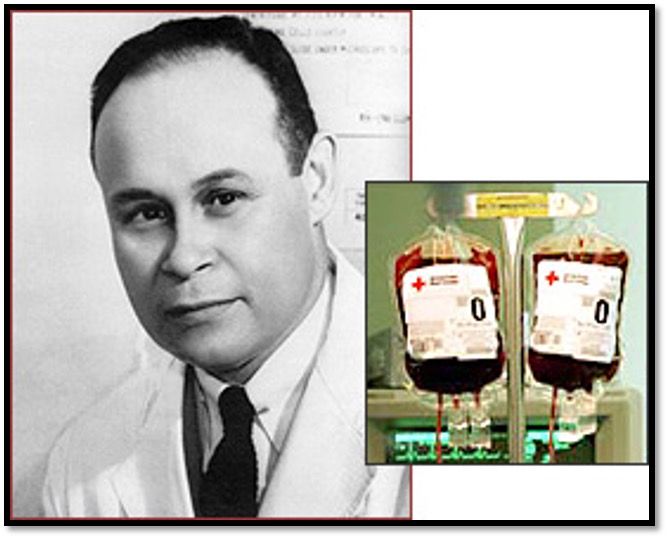

Dr. Charles Drew

Surgeon and medical researcher

Dr. Drew revolutionized the understanding of blood plasma. His research in blood transfusions improved methods for blood storage. His work benefited allied forces in World War II where he served as the medical director of the United States’ Blood for Britain project. He helped set the standard for other hospitals donating blood plasma to Britain by ensuring clean transfusions that prevented contamination. Dr. Drew developed large-scale blood banks in the war, and he recruited 100,000 blood donors for the U.S. military. But later he would resign his position as the first director of the American Red Cross blood bank because of their practice of segregating blood according to race. He said it lacked a scientific foundation. The Red Cross continued the racial segregation of blood until 1950.

Born in 1904 into a middle-class Black family, Dr. Drew grew up in an integrated Washington, D.C. neighborhood. He had a paper route as a boy and attended a high school known for equal opportunity despite the racial climate during that time.

Dr. Drew won an athletic scholarship to Amherst in Massachusetts. After graduating in 1926, he earned money for medical school by working as a professor of chemistry and biology, and the first athletic director and football coach at the historically Black Morgan College in Baltimore.

During medical school at McGill University in Canada, Drew worked with John Beattie who was conducting research in the potential correlations between blood transfusions and shock therapy. At McGill, he achieved membership in Alpha Omega Alpha, a scholastic honor society for medical students, and ranked second in his graduating class of 127 students. He received a Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degree in 1933.

Working on his thesis at Columbia University, Dr. Drew developed a method for processing and storing blood plasma. He became the first African American to earn a Doctor of Science in Medicine degree.

In another first, Dr. Drew joined the American Board of Surgery, becoming the first African American examiner in 1941.

A common myth is that Dr. Drew died because of racial segregation. The myth goes that following a car accident in Alabama he was refused bed space and a blood transfusion because there weren’t enough, “Negro beds” available. One of the three doctors who survived the accident said that was not the case, and that Drew could not have survived a blood transfusion because his injuries were too severe.

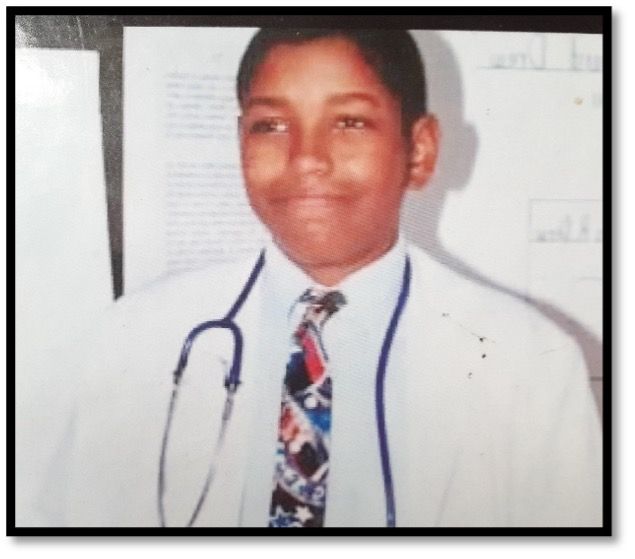

At age 12 my son portrayed Dr. Charles Drew for a school living biography project. And here he is today.

And my money-loving daughter became an investment banker---which was no surprise to anyone. LOL. Proud mom? You bet.

But the important point is that their dreams never seemed beyond reach because they didn’t assume these professions were only for white people. They learned of the accomplishments of African Americans in many professions, and throughout history.

This is one of many reasons why I believe that history should not be tampered with for political reasons but presented universally and inclusively. We should learn of the contributions and accomplishments of women, Asians, Latinos, Indigenous Peoples, those who identify as LGBTQ---in addition to the contributions of white males. Segregated history is not real history.