Black History Month: The Home of the Brave

It is often the unsung heroes that make outsized contributions to the black community. For Black History Month, it's a good time to recognize the few who had cojones of steel in the face of enslavement, oppression, and violence.

February is the month I like to read and write about Black Americans whose contributions to America's history were left on the cutting room floor. It's also a time to give Texas critical race theory the single-finger salute. I begin this month with a few men and women who had cojones of steel in the face of enslavement, oppression, and violence.

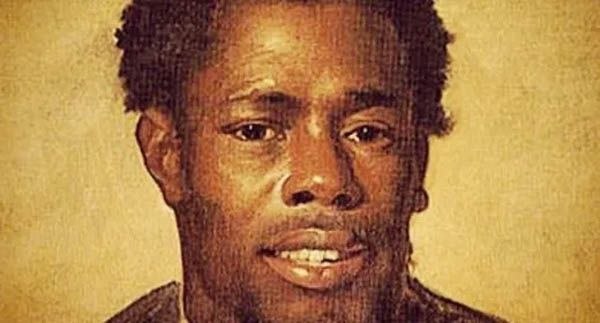

He said God told him to lead a revolt and to kill his oppressors. So, he did. Nat Turner, an enslaved American, used preaching to build his Virginia freedom rebellion, known as the Southampton Insurrection, in August 1831. Between 55 and 65 White enslavers were killed in the deadliest slave revolt in U.S. history. The rebellion only lasted a few days and Turner survived in hiding for more than two months afterward.

In return, militias and mobs retaliated and killed as many as 120 enslaved people and freed African Americans, another 56 were convicted at trial.

It was because Turner was educated and was a preacher, Southern state legislatures passed new laws prohibiting the education of enslaved people and free Black people, restricting rights of assembly and other civil liberties for free Black people, and requiring White ministers to be present at all worship services.

Turner was hanged for leading the insurrection.

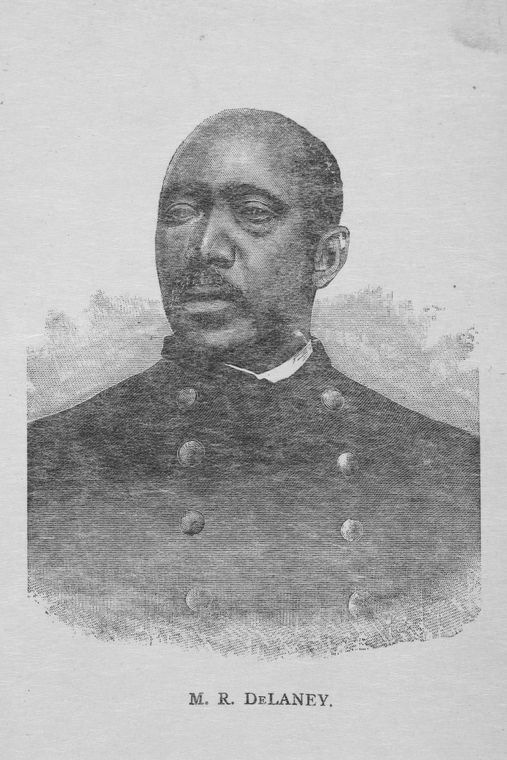

Martin Delany was an abolitionist, journalist, physician, and writer. He led the Vigilance Committee which helped relocate fugitive slaves. He also founded the first African American newspaper west of the Allegheny, The Mystery. Delany was commissioned as major and the first African American army field officer during the Civil War. He was one of three Black men to enroll in Harvard Medical School in 1850. All three were dismissed after a few weeks because White students protested.

Delany was born a free person of color in what is now West Virginia. As a physician’s assistant he was willing to treat patients during cholera epidemics when many doctors fled to avoid contamination.

In 1839, he went to the south to witness slavery. Later he worked with abolitionist, Frederick Douglass publishing the anti-slavery newspaper, North Star.

Delany ran for Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina as an Independent Republican. He switched parties to Democrat after violent suppression of Black votes and ballot fraud by the white supremacists known as Red Shirts.

Delany was also appointed a trial judge but removed because of scandal. He and Douglass had a public feud in the Black press over their philosophies of how African Americans should escape U.S. oppression and gain freedom. Delany believing in emigration; Black people should flee the country and fight from the outside in, Douglass believing the opposite, that the fight for freedom should happen on U.S. soil.

Delany wanted to establish a settlement in West Africa for free Blacks. But political activism, work to support the Underground Railroad, and family obligations waylaid that dream.

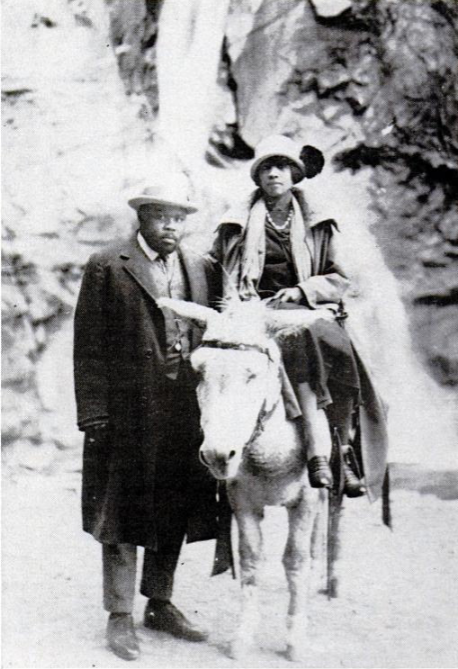

The most well-known figure in the Back to Africa movement was Marcus Garvey who believed African Americans should not live in white-dominated societies. But I believe both of his wives are a bit unsung.

She stood in front of her husband to prevent an attempted assassination. Amy Ashwood Garvey was married to leader of the United Negro Improvement Association, she was a co-founder of the organization, and a force in her own right. Both she and her husband were born into middle and upper middle-class families in Jamaica.

She organized a women's section of the UNIA, and in 1918, moved to the United States. Here she worked with Garvey as the association’s secretary. She later became secretary and eventually one of the directors of Garvey’s shipping line, the Black Star Line.

But the marriage of the Garvey’s was tumultuous and carried accusations of infidelity on both sides. Following their divorce in 1922, she continued as a Pan African activist and early feminist before moving to London.

Marcus Garvey married another Amy, Amy Jacques, the former roommate and maid of honor of Amy Ashwood. Jacques was from of a mixed race middle class Jamaican family, as well. She was reportedly enthralled by Garvey and his philosophy. She worked as his secretary in UNIA.

Marcus Garvey was deported in 1927 following indictment for mail fraud, and Amy followed him to Jamaica.

After his death in 1940, Jacques continued the struggle for black nationalism and African independence. In 1944 she wrote "A Memorandum Correlative of Africa, West Indies and the Americas", which she used to convince U.N. representatives to adopt an African Freedom Charter.

She later published her own book, Garvey and Garveyism, in 1963, as well as a booklet, Black Power in America: The Power of the Human Spirit, in 1968. Her final work was the Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey volume III, written in collaboration with Nigerian professor, E. U, Essien-Udom.