Black Jack's Backlash

Although “Black Jack” spent only about eleven months in pursuit of Villa, he publicly claimed a putative victory by scattering the “Villistas,” revolutionaries who had followed Villa. The general in a letter to a friend, though, acknowledged the failure of his massive endeavor.

There is smooth, flat rock on the bottom of the Rio Grande, near where the river makes a bend toward the walls of Santa Elena Canyon. The water is shallow on that stretch of the water course, which turned it into a natural crossing point. Indigenous peoples like the Comanche and Apache used the location to hunt on both sides of the river before there were governments and countries with names and borders and flags and armies. Eventually, Mexicans and Americans found the spot convenient for conducting trans-border business and congregating with friends and families living on both sides of the river.

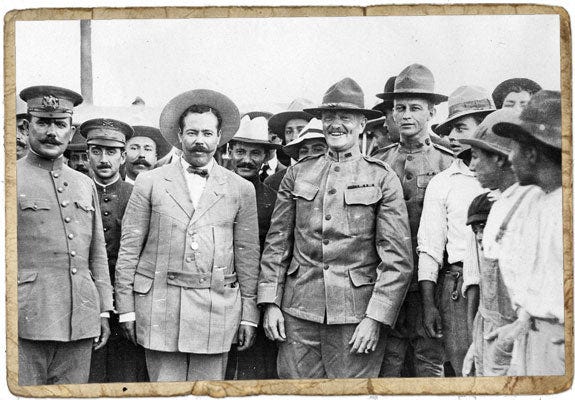

Shortly after the beginning of the Twentieth Century, soldiers in uniforms of the United States military were bivouacked on a hill downstream from the crossing. They were under the command General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who had been given his nickname because he had served with Black soldiers in the Tenth Cavalry during the Santiago Campaign of the Spanish-American War in Cuba. Pershing, tall and patrician in bearing, had been given orders by President Woodrow Wilson to pursue Pancho Villa in Mexico, and put an end to his depredations on the U.S. side of the Mexican border.

Pershing, who had been promoted to Brigadier General by Teddy Roosevelt, had taken command of Fort Bliss outside El Paso. Not many miles distant, Villa had sacked the Southern New Mexico town of Columbus, killing 17 Americans and setting flame to the community’s structures. Villa was trying to overthrow his country’s government with a revolution but consistently viewed the U.S. as intervening and causing further military and political challenges. Pershing crossed the border heading south toward the Sierra Madre Occidental, determined to pacify the outlaw and his bandits. Villa was to be captured or killed.

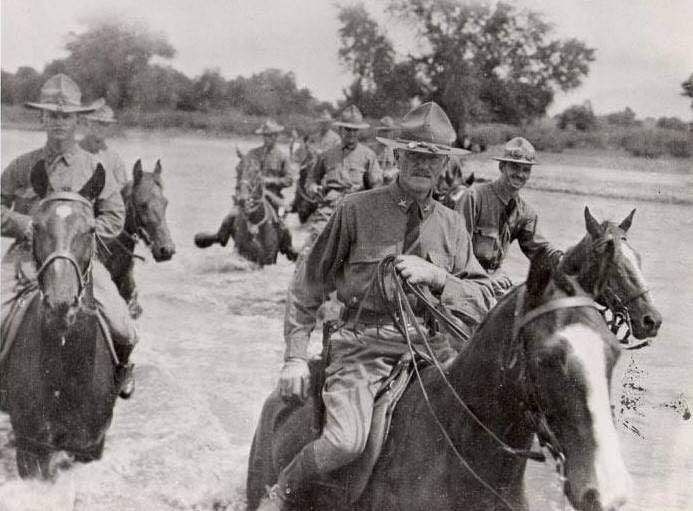

The general reportedly took 9,000 soldiers with him and, prior to his departure, as many as 50,000 U.S. National Guard troops had lined the border to protect Texas from Villa. An unknown number of them were stationed just west of Santa Elena Canyon in a location later to be known as Lajitas, which refers to “little, flat rocks.” The low spot with the flat-rocked riverbed, which was where the troops crossed into Mexico on their pursuit of Villa, became known as “Black Jack’s Crossing.” Whether the general was ever present to lead those men across is not known for certain, though there are several photos of him riding his horse into the river and southward. His original campaign launched near the Texas-New Mexico line, not far from Columbus on March 16, 1916.

Be sure and subscribe to receive our stories weekly.

If you can, we'd love it if you'd become a paid subscriber.

The Mexican Revolution lasted ten years from 1910-1920, and there were concerns early that the political leadership of Mexico was clandestinely getting military assistance from Germany, which was poised to launch the first global war in Europe. Pershing, meanwhile, who later became the commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force confronting the Kaiser’s soldiers, never even caught sight of Pancho Villa even as talk of international wars escalated. His interdiction south of the border resulted in skirmishes, and one disastrous loss of men, horses, and materiel in a battle at Carrizal, less than two weeks after he had crossed the frontier. Villa had also plundered Nogales, Arizona and stopped a train carrying American railroad surveyors. He promptly executed seventeen men, without expressing remorse or facing punishment.

Villa’s ability to disappear into the mountains around Chihuahua made Pershing’s task almost impossible. The general was the first American military commander, however, to deploy aircraft to conduct reconnaissance to find roads and trails and signs of the evasive revolutionary. Heavy trucks used by Pershing to haul ammo and supplies were never able to move sufficiently fast enough over Mexico’s mostly dirt roads and could not close on the rebel and his men. The U.S. was also never able to press an advantage using the airplanes. Although “Black Jack” spent only about eleven months in pursuit of Villa, he publicly claimed a putative victory by scattering the “Villistas,” revolutionaries who had followed Villa. The general in a letter to a friend, though, acknowledged the failure of his massive endeavor.

“When the true history is written, it will not be a very inspiring chapter for school children or even grownups to contemplate. Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped curr with its tail between its legs."

Villa lived on without worrying about Pershing’s “Punitive Expedition,” but met his fate in 1923. A former Mexican congressman, who had been pistol whipped by Villa in an argument over a woman, led an assassination squad that killed him in an ambush as he drove to meet a lawyer in Parral. The revolutionary leader was on his way to have his will rewritten.

Pershing, though, had been picked by President Woodrow Wilson to lead American forces in World War I and played a role in the framing of the Treaty of Versailles when Germany finally sued for peace. The general was disinclined to accept the offer and wanted to continue prosecuting the war because he believed its leaders would not be politically chastened unless the conflict was punitive to conclusion, and the Kaiser’s army was destroyed. His belief was that the Germans had to be eliminated on the battlefield, troops and weapons, or they would be back to arms in another generation, which, obviously, turned out to be correct. The treaty provided Hitler with leverage to make his claims that the German people had been historically wronged and needed to ascend to their rightful place of power, which had been abrogated by peacemaking. He convinced his nation that the armistice was unfair to the German people and that they had been betrayed by politicians who had assented to its terms, which amounted to “stabbing the army in the back.”

Tom Russell’s Ballad on Pershing’s Pursuit of Villa

There is something politically allegorical to Pershing’s aggressive stance that lurks in today’s American presidential politics. Efforts to use the Fourteenth Amendment to disqualify Trump from getting on electoral ballots in various states, which could doom his candidacy, might offer America an historic backlash. No argument exists to suggest Trump did not attempt to overthrow a duly elected government, and that makes him subject to being banned from ever again running for, or holding public office in this country under Sec 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The evidence is abundant and manifest, but the strategy seems shortsighted and adorned with risks. He needs to be defeated at the ballot box, soundly and with great emphasis on rejection by the American electorate. There must be no doubt this nation is done with his histrionics and nascent authoritarianism.

A friend of mine said, “We need to beat his ass into the ground.” If Trump were to be disqualified, and the U.S. Supreme Court denies any appeals to stop his removal from various state ballots, MAGAts will have a grudge to carry until they tear down the country and the Constitution. Trumpistas will not be appeased, regardless of how loudly the country will have spoken, but we still must make his rejection sound and final. Right now, Trump is moving toward a GOP coronation, and the remaining sane members of his party, who are disgusted with the man, feel the Republicans are forcing the Mayor of Mara-Lardo down their throats. This is akin to what the Democrats did in their selection of Hilary Clinton in 2016. If the irony needs pointing out, it is this: Donald Trump has become the Republicans’ Hilary Clinton.

Meanwhile, down on the Rio Grande where Black Jack’s men crossed the river, the residents of both countries are developing traditions to heal the wounds of politics. The spot just west of Lajitas, which was once an official border crossing, has become the site of a frequent gathering of friends and families that live with a river in their midst. In the Voices from Both Sides celebration in the spring, people gather in the river and on both banks, north and south, to renew friendships and reconnect their families and enjoy the desert beauty. There is food and music and swimming, maybe a beer or two, and on the hill not too distant, the Border Patrol watches with a discerning eye. The ghosts of Pershing and Villa are likely around, too, baffled by the human behavior.

Shall We Gather at the River?

When Villa died in the ambush, he was armed with two .45 pistols and accelerated his car into the gunfire. What’s left of that moment, and his legend, is the story, and a blackened finger sitting in the window of an El Paso pawn shop. The owner claims it is Pancho Villa’s trigger finger, and he’s been trying for years to sell the human remains for $9500 dollars. No takers. Villa never got around to using it when he was assassinated, and the pawn shop owner cannot guarantee the digit’s provenance.

On the bend in the river today, a golf course resort bears the name of Black Jack’s Crossing, which is actually just upstream from the green fairways and tee boxes set in the brown and ochre desert rock. Private aircraft fly duffers to the 18-hole course from the major Texas metros. Some stay in hotel rooms that are located on a spot where Pershing’s men were bivouacked in canvas tents while awaiting orders to run the revolutionary to ground. They would probably be unsurprised to learn the world makes less sense now than it did even when they were mounting up.