Houston’s Frenchtown: Let’s Not Disregard the Creole Culture

Creole? Cajun? What's the diff? South Louisiana survivors of the 1927 Great Mississippi flood who settled in Houston's 5th ward can tell you.

In the early 1990s, I attended an event in Houston’s Frenchtown and was transformed to South Louisiana, the homeland of my parents and where I lived for a time and went to college. The event was bilingual, the food was authentic, and I met a cousin or [kou-zahn] there. I hope it can survive the waves of time.

How Frenchtown Began

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 left many South Louisiana Creoles devastated and homeless. They relocated to Houston’s Fifth Ward area, between the boundaries of Collingsworth, Russell, Liberty Road, and Jensen. As with most people, their language, food, music, rituals, and other cultural aspects moved with them. The community became known as Frenchtown, a place where many older people didn’t speak or understand English. The residents had their own schools, church, and businesses. They chose Houston because of the number of jobs for skilled laborers; mechanics, carpenters, sawmill workers, or bricklayers They worked for Southern Pacific Railroad, the oil industry, or other industries along the Houston Ship Channel.

Keep Creole and Cajun Separate & Complicated

The traditional differentiators of the two are summed up as with most things in this country, according to race in simply black and white. Creoles have been defined as having African, European, and Indigenous lineage, while Cajun, all that minus the African. Creoles, more heavily influenced by the French; Cajuns known as Acadians, originating in Canada not France. But the differences are not that simple.

The term Créole was originally used by French settlers to distinguish people born in Louisiana from those born elsewhere, drawing a distinction between Europeans (such as the French and Spanish) and Africans born in the Old World from their Creole descendants native to the New World. The word is not a racial label, and people of fully European descent, fully African descent, or of any mixture of those (including Native American admixture) may be Creole.

Today, cultural authorities suggest a more comprehensive view of the definitions, and the ability for Creoles to self-define their own communities. One of those authorities is my cousin, Andrew Jolivette, Chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego, author, and sociologist. In his book, Louisiana Creoles: Cultural Recovery and Mixed-Race Native American Identity, Jolivette questions, “the process of cultural formation and the politics of ethnic categories for multiracial communities in the United States.” Additionally, in the book, Louisiana Creole Peoplehood, Afro-Indigeneity and Community, he writes “Too often in under-researched and marginalized communities we tend to over assert the knowledge of academic “experts” without acknowledging that cultural keepers and everyday citizens provide the basis for what expertise we may call on to conduct our research.”

It’s easier for humans to categorize people by simple means, like skin color, rather than attempt to comprehend the complexities of mixed-race and culture. It’s too much work. When you’re Black with a French name, Indigenous ancestry, or as with many Creoles, white skin, and blue eyes, you don’t fit the stereotypical mold. This makes recognition challenging for a community like Frenchtown where cultural identifiers are layered.

Culture Defined

Culture can be defined as all the ways of life including arts, beliefs and institutions of a population that are passed down from generation to generation. Culture has been called "the way of life for an entire society. It includes codes of manners, dress, language, religion, rituals, and art.

Louisiana Creoles share cultural ties in the use of traditional French, Spanish, and Louisiana Creole languages, and the predominant practice of Catholicism.

Shortly after their move to Houston, Creoles broke ground on their own church in April of 1928, called Little Mission Church, now known as, Our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church. Educational classes began there in 1931 with 166 children, according to Denise LaBrie, a Grammy nominated songwriter, author, and poet. LaBrie’s family was among the early migrants to Frenchtown. Among her works are, The Creole Chronicles, and Parle Creole: Southern Louisiana Dialect. “By 1942, the church had a congregation of 2,000 and 434 students attended the school.”

Before Our Mother of Mercy was built, Frenchtown residents had to walk three miles or take a streetcar to St. Nicholas Catholic Church at Clay and Live Oak. It was the only Catholic Church in Houston for people of color. They held dances and sold unique Creole cuisine of gumbo, boudin, and pralines to raise money to build the neighborhood church.

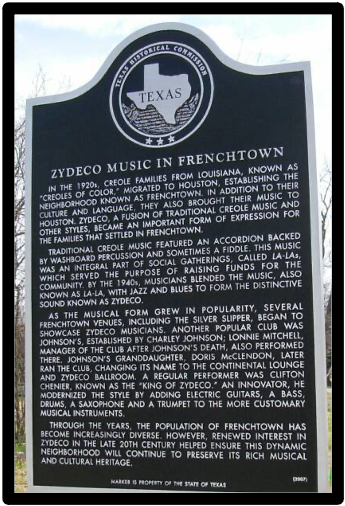

The Texas State Historical Association gives this account of Frenchtown: Their community of largely French-speaking Catholics was centered around Our Mother of Mercy Roman Catholic Church and had a rich Creole culture distinguished by its colorful patios, unique cuisine, and characteristic zydeco music. Historical markers at Collingsworth and U.S. Highway 59 and at Liberty and U.S. Highway 59 commemorate Frenchtown and its role in developing zydeco, a blend of traditional Creole music with Houston’s blues and R&B.

The tight-knit group married within the community and maintained their cultural identity. Many residents built their homes with lumber from boxcars. Neighborhood streets were dirt roads; residents used streetcars for transportation and walked to Jensen Drive and Liberty Road to ride them. The women of the community refused to take employment as cooks, despite the appeal of their cooking.

Residents of Frenchtown had a distinct language, religion, cuisine, music, and in some instances light skin color that separated them from the larger Black community in the Fifth Ward. These differences caused some resentment in the Black community. Some Frenchtown children were ridiculed in school due to their language, and for some adults, language made assimilation difficult, so parents eventually discouraged the use of French by the children. Some changed their names on arrival in Houston.

A Good Fais-dodo (Sunday Zydeco dance parties where babies slept while their parents danced)

Zydeco is a style of music from southwest Louisiana that draws from Black American blues, Louisiana French Creole, and Native American musical cultures. It evolved into its present form in the 1950s under the influence of Clifton Chenier, who is called the king of zydeco. Frenchtown venues like the Continental Ballroom and Alfred’s Place were central to the dissemination of zydeco music. And the Creole Knights was an established social club that included 12 members of the first families to move to Frenchtown.

The Signs of Time

Frenchtown, like many communities, has changed. As the older generations passed on, Creoles married outside of the culture, and younger Creoles moved out of the neighborhood. The community largely merged into Fifth Ward. There are also the common challenges all urban centers struggle with, such as gentrification, urban blight, and the intrusive development of freeways and other non-residential structures.

While it seems the Frenchtown Association still exists and a Facebook group is named for Houston’s Frenchtown, I couldn’t tell how much of the community is intact or acknowledged today.

Unfortunately, the blurred lines of race and culture are saddled with a heavier lift in receiving recognition and respect. In a world that prefers to swipe a broad brush over Brown and Black people to conveniently make them all the same, how do enclaves such as Frenchtown take and hold a place as culturally significant, unique, and worthy of remembrance in our communities?