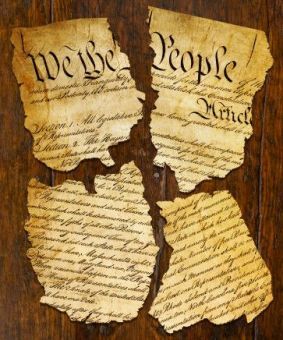

Independent State Legislature Theory and the Threat to Democracy

The Supreme Court is hearing a case that could forever change the way we conduct elections in this country – almost certainly for the worse.

December 7, 2022

The Supreme Court of the United States, or SCOTUS, is hearing a case today called Moore v. Harper, and their decision in that case has the potential to transform American democracy as we know it. I know that sounds kind of apocalyptic, but we seem to live in apocalyptic times.

Moore v. Harper invites SCOTUS to validate the so-called “independent state legislature” theory, which would have profound impacts on how we conduct elections in this country. To understand that, we should start with how state-level policymaking is generally conducted now.

How State Governments Work

Every state in the country has the same three-branch, separation-of-powers organization as the federal government: legislative, executive, and judicial.[i] Ultimate policymaking power is granted to the legislative body, no matter what it’s called: the Legislature, the General Assembly, the Legislative Assembly, or even the General Court (as in New Hampshire). In every state except Nebraska, the legislature is bicameral, i.e., there’s a house and a senate. Legislatures set overall state policy by passing bills and approving the state budget.

Importantly, there are checks and balances on a legislature’s activity, both in the executive and judicial branches. A governor can veto a bill, for instance. Executive branch agencies have rulemaking authority that can flesh out the practical implementation of bills, sometimes in ways the Legislature may not have anticipated. And in Texas, for instance, the Comptroller must certify that the budget numbers add up before the budget can take effect.

Every state also has judicial review of legislative acts. State courts can strike down all or part of a legislative enactment, because of conflict with either the state constitution or another legislative enactment. Federal courts can also get involved, if a legislative act is thought to violate either the federal constitution or statute.

This structure has always applied to the conduct of elections, including federal elections. Two provisions in the Constitution give state legislatures the responsibility for conducting federal elections. Article I, Section 4 says “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of [choosing] Senators.” A separate provision (Article II, Section 1) set forth state responsibility in the choosing of a President and Vice President: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.” (emphases added)

For 234 years, those phrases were understood as granting those powers to the legislature in the same way as all other legislative powers operated; to wit, subject to the checks and balances of the particular constitutional setup of each state.

Independent State Legislature Theory (ISLT)

But, as is often the case, there’s a glitch in the Matrix: Independent State Legislature Theory, which holds that the Constitution’s references to “Legislatures” in those two provisions means only the legislatures, and the normal constitutional checks and balances on state legislatures – governors, state agencies, courts – have no say in these matters.

ISLT has been explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court twice, the last time as recently as 2015. But the archconservative supermajority on the current Court is developing a reputation for blowing shit up – witness the Dobbs decision repealing Roe v. Wade – and four members of the Court have expressed interest in applying the theory to the North Carolina legislature’s redistricting plan, which had been struck down by North Carolina courts.

In the old days when I was in law school, we were taught reverence for the concept of stare decisis – the idea that precedent should be a controlling factor in making legal decisions. This was explained to us as fundamental to having an intelligible legal system on which people could rely. If every time, say, a gay couple wanted to marry, we had to relitigate Obergefell, the 2015 SCOTUS case affirming the right to gay marriage, we’d never get anything done. (This example is not entirely speculative: in his concurring opinion in Dobbs, Wicked Step-Uncle of the United States Clarence Thomas suggested that Obergefell should be revisited.)

More to the point, there’s no evidence that the Founding Fathers intended such a narrow interpretation of the word “legislature” in those clauses. This is an example of taking “originalism” and “textualism” – the philosophical underpinnings of the “Protect the Patriarchy” movement – to absurd lengths in order to reach ideologically-preconceived results.

What Would It Look Like?

So, if ISLT were adopted, what could go wrong? Here are some examples.

Let’s say a legislature, dismayed by the “chaos” caused by mail-in ballots, passed a bill to eliminate them and permit only voting in person. This would disenfranchise people in nursing homes and overseas/military voters, among others. A governor might veto such a bill, and a state court would likely strike it down. Under ISLT, though, such challenges to that law would not be allowed.

Or a legislature could pass a bill requiring hand counting of ballots and requiring that the count must be completed by noon the day after an election. Whatever wasn’t counted by then would be ignored. This would undoubtedly disenfranchise a large percentage of voters (perhaps even the majority), but the bill would not be subject to court review.

You can see there are thousands of ways to legislatively screw up the fair and free conduct of elections by tinkering with the mechanics. But it could get worse.

Right now, in every state, the law is that the person who gets the most votes wins the presidential election. The current political battles are over how elections are conducted and votes are counted. But what if a legislature said that it retained the right to review a presidential election and its outcome, and if it thought that, because of irregularities, or fraud, or a snowstorm on election day, the true will of the people had not been expressed, it could substitute its judgment for that of the electorate?

This is the nightmare scenario that ISLT makes possible, even if not likely. It is thought unlikely because the voters would never put up with such a law. But really? Why wouldn’t the GOP-controlled Arizona Legislature pass a bill giving it the right, in the event of "fraud and mismanagement by local elected officials" – remember, significant portions of the Arizona legislature made exactly that argument about the 2020 election, and some are making it about the 2022 midterms – to substitute its set of electors for those “chosen” by the voters, even though they have a Democratic Governor and Secretary of State? Especially because they have a Democratic Governor and Secretary of State? And why wouldn’t a majority, even a slim one, of Arizona voters support such a law?

This would only be relevant in a battleground state like Arizona, where Biden won by less than 11,000 votes in 2020. But here, for the sake of the argument, is how you would do it in Texas.

In the event that the Governor, in consultation with the Lieutenant Governor and Speaker, determines that a presidential election just held was hopelessly compromised by voter fraud and electoral mismanagement to the extent that the true wishes of the voters of Texas cannot be ascertained, the Governor may convene a special session of the Legislature, to begin on the last Monday of November, for the sole purpose of determining from the available evidence whether it is possible to know the winner of the last election. Such a determination must be made by a 60% supermajority vote of both chambers. In the event that occurs, the Legislature may, by another 60% supermajority vote of both chambers, substitute its own slate of electors for submission to the Electoral College. In no case can the special session last longer that one week, and this is the sole item that can be placed on the agenda.

There. Someone smarter than I should check my homework, but I do not think that would require a constitutional amendment, so it could be enacted by simple majorities of both chambers. In fact, the current GOP majorities in the Texas Lege should pass such a bill now, as a hedge against the distant but imaginable time when they will not be in charge. (It’s easier to pass a bill than it is to repeal it.)

My point is this: SCOTUS endorsement of the independent state legislature theory could open a Pandora’s Box of mischief – and to what end? One clue is the identities of the SCOTUS members who openly called for the case to be heard: Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, possibly the most nakedly partisan members of the Court.

The gravamen of the ISLT argument is that state courts should not be able to review legislative enactments about federal elections. The likely results of adopting ISLT is more partisan meddling in elections with no effective check by the courts and correspondingly less confidence in the electoral processes that are at the heart of our democracy. How fun!

Send Lawyers, Guns and Liquor

Your Humble Correspondent is ruining his day by listening to the oral arguments. Assuming he has not day-drunk himself into a stupor, he will provide an update on the oral arguments to his faithful readers as soon as practicable.

[i] I could make a snarky remark about Sen. Tommy Tuberville’s (R-AL) identification of “the House, the Senate and the President” as the three branches of government, but I won’t. Besides, Chuck Schumer said a similar thing.