On the Loose

"I never stopped returning to the Grand Canyon and never will. There is no medication to cure political and emotional ills coursing through your country and your brain but one hike into the canyon can temporarily render them into near irrelevance."

“My salvation is that I was not born into the adolescence of my race. Its beautiful childhood may be gone, but its manhood is now. Evolution is aware of itself. At the last hour of the planting season, the seeds of a universal sanity are sown.” - Terry and Renny Russell, On the Loose

More times than I can recall I have sought sanctuary from my country’s politics. Americans, too often, hell, perhaps always, appear to claw at each other’s flesh over matters that ought to be resolved by civilized public discourse. We do not, however, function with a group intellect and shouting can turn to organized protest and that slips, sometimes, into violence. I came of age as a young man during the War in Vietnam and marched the streets of Washington, D.C. with my generation to protest the immoral war. I thought I was part of a profound political movement and I was helping to exorcise my country’s guilt and end needless dying.

But I was also afraid.

The U.S., as it has in much of the past decade, felt frequently close to coming undone. Too much evidence piled up to indicate a vote did not matter and the cons running wars and defense contractors and energy companies were simply going to continue greed and wealth accumulation and did not care what died along their route of travel. The construct that makes this sadness inevitable has always been a part of America’s history and attempts to do the right thing tend to be throttled by wealthy lobbyists and their special interests and religious fraudsters selling magical thinking about what their god wants us to do as a democratic nation. We, the people, though, do not appear to run our own country, and likely never have.

Which is why I have always run to the woods. Or, mainly, the desert. And no place has attracted me more than the Grand Canyon. I do not know the number of times I have stood at the South Rim and looked down on Bright Angel Trail winding toward the Colorado River and have felt a physical change come over me as if I were sensing my blood pressure ticking downward. There is some emotional catharsis that arises when looking out across the eons of upthrusted rock strata and erosion and thinking that the Earth will, in fact, abide, regardless of our sentient tendencies toward mutual destruction of humanity and its environment. What good is natural grandeur, though, if there are no eyes to view its glories, no tears to fall in response to beauty?

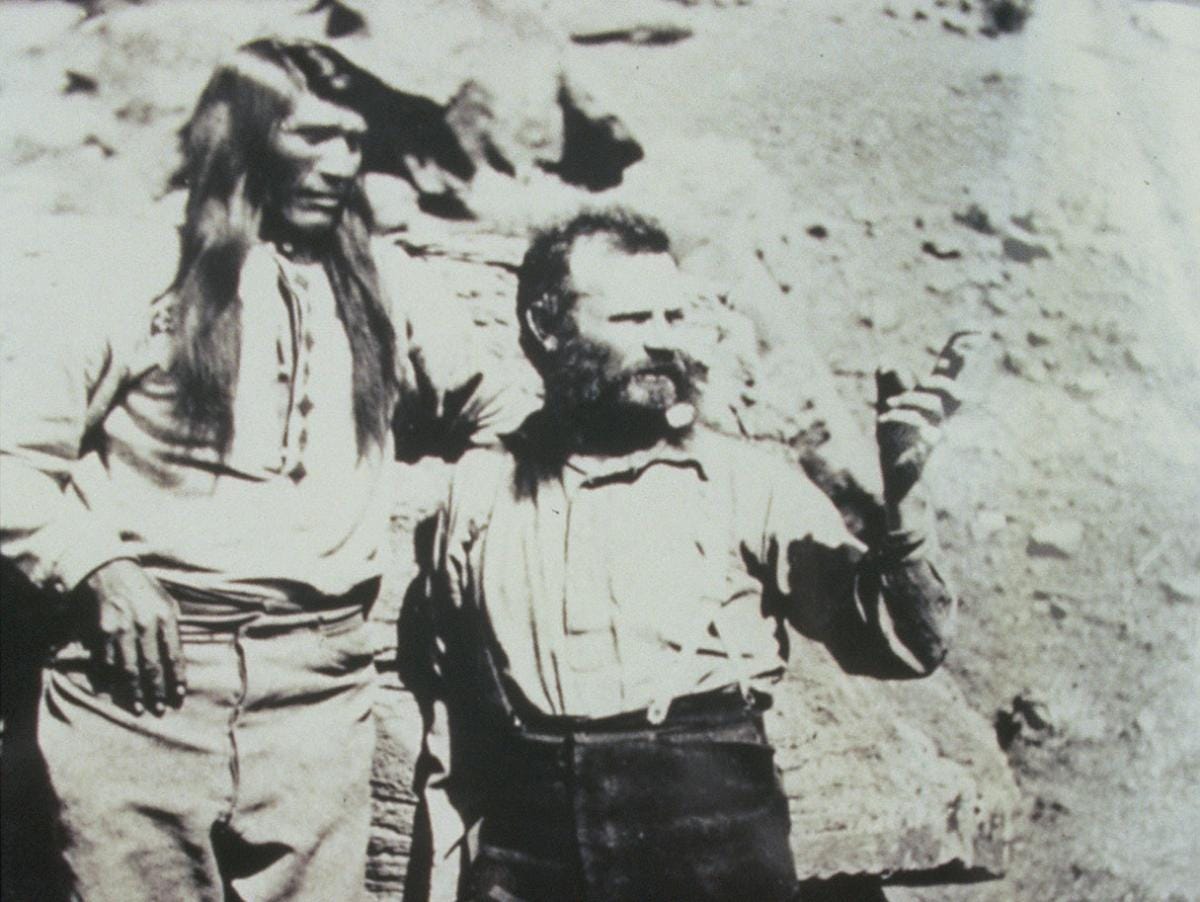

My first trip to the canyon was motivated by healing as much as adventure. I was still too naive to comprehend my personal injuries from a violent father but I was adequately aware to realize my friend Butch had broken parts inside him after returning from Vietnam. He did not talk about the war unless he was very stoned but he was enthused enough about seeing the canyon that he had agreed to hitchhike out from Michigan with me. Our trip took more than a week because Butch did not look like a soldier who had just pounded through Southeast Asian rice paddies and jungles in service of his country. We both had long hair and his beard was ragged and untrimmed and we slept beneath overpasses and in dusty, unplowed fields beneath scrawny mesquite trees.

Shortly after we began our descent into the canyon, I sensed Butch was becoming engaged in our hike when he pointed out striking geologic forms and how plants had grown up out of solid rock. There seemed hope our planned crossing to the North Rim might have a kind of curative effect I had hoped for my friend. The declination of the sun as we walked sent a shadow chasing us down the trail and we barely had light to get our tents erected at the campsite of Indian Gardens. Before I had finished dealing with my gear, Butch had drifted over to a picnic table to talk to another small group of our contemporaries. I saw this as additional indication of change because he had been mostly silent on our long ride west.

A joint was being passed around a picnic table when I walked up. The four had a bright camp light and I saw a girl with thin blonde hair and a pointed chin smile at Butch. She had long slender hands with fingernails painted red and a tiny nose and the smile he returned to her made me happy, and slightly jealous.

“Where are you two from?”

A guy wearing loose beach trunks and sandals exhaled the question with marijuana smoke. I was not able to see much more than his legs because the night had come up so full and fast and he was outside of the reach of the camp light.

“We came down from Michigan,” I answered.

Butch turned to me and laughed. “Not me,” he said. “I’m from Vietnam. That’s where I came from.”

“You were over there, man?” the beach guy asked.

“Yeah, two tours. A year and a half. Kill, kill, kill. Just like they wanted.”

Butch seemed to have quickly gotten stoned on a few tokes and was again sounding angry. I was worried.

“You killed people?” A taller and darker girl was standing out of the light and she had heard Butch mention combat.

“Sure,” he said. “Lots of ‘em. Had to, or they would’ve killed me.”

That’s fuckin’ awful, man,” she said.

“Well, I’m here and they’re not, so that’s all any of it means to me. I guess it was more fuckin’ awful for them than me.”

“You mean you weren’t fighting to keep us all free like they tell us?”

Butch laughed. “You can’t be serious. Fuck no. I was fighting to stay alive. That’s all. That freedom shit doesn’t have anything to do with Vietnam and you can ask anybody who carried a gun into the jungle.”

The guy in the beach shorts was concerned about his prospects in the war and made the mistake of seeking assurances from Butch.

“I’m gonna get drafted,” he said. “I know it. Just graduated from U.C.L.A. This might be my last summer on planet earth and I just turned twenty fuckin’ one. Ain’t that great shit?”

“You might not get drafted,” Butch said. “Just no way to know.”

“What the hell are you talking about, man? I drew number three in the lottery. I’m outta here. I bet my notice for physical induction is waiting for me when I get back to L.A. Hell, maybe I’ll never go back.”

“I wouldn’t,” Butch said. “Good chance you’re gonna end up dead if you go in. You look like all the guys I saw die. You could see it on ‘em when they showed up at the base for processing. Looked like they’d been captured and drugged and woke up in Vietnam. Most of ‘em were dead in a week or two.”

“Fuck me,” the beach guy said. “Gimme that joint back.”

Butch was swaying a bit like he heard music that no one else’s ears were able to pick up and I noticed he had begun staring at the ground.

“This is all so fucking stupid,” he said, abruptly. “Here I am in the Grand fucking Canyon, surrounded by nature or god or whatever, and I can’t get away from having to talk about that goddamned war.”

Everyone was silent as he got up and returned to his tent. I followed without comment. Butch woke me the next morning before daylight came up over the canyon rim and we were down by the Colorado River in a few hours, standing on the suspension bridge. We slept that night on the sand spun loose for millennia along the bank and l kept waking up to listen to the river’s eternal roar. Butch was back to being disaffected for most of our climb up to the North Rim the next day and when I called home and discovered his mother had died of a heart attack, we hurried back to Michigan in a car his brother had rented to get us home. My friend took no cure from nature’s wonders and never went back to the canyon.

I never stopped returning, though, and never will. There is no medication to cure political and emotional ills coursing through your country and your brain but one hike into the canyon can temporarily render them into near irrelevance. Only nine months ago, I rode motorcycles with two friends out from Texas to camp on the South Rim. Autumn months are less crowded without the rush of car-camping families from L.A. and Phoenix who are finally busy at home with work lives and schoolchildren. The loudest sound at night was the wind high up in the ponderosas; not the music of the spheres but almost as lovely and played only by the rustling of pine needles. The Milky Way whorls up across the canyon with such detail the uninitiated mistake it for a cloud rolling down from the plateau country of Southern Utah.

I dreamed that first night of spreading my arms and flying down the Colorado from Lee’s Ferry to Havasu Falls and up Kaibab Trail, across the Coconino Plateau and then rising high enough to see the entire canyon in one view. I have always wondered what the exploration of the river was like for John Wesley Powell, the Civil War Veteran who lost an arm to a mini-ball, and conducted the first scientific survey of the Colorado and the canyon’s geologic evolution. Powell and his small team rode giant rapids and confronted river boulders in wooden boats while stopping to measure positional coordinates, note landforms, barometric readings and elevations, geographic features, and record the river’s course toward the sea. Their deprivations during the exploration were many and manifest. Powell’s research and perspective, however, developed 160 years ago, laid the foundation for how the federal government manages national resources and park preserves. His scientific approach was essential to understanding the unexplored American West and has helped prevent its complete desolation by economic predators and mining companies.

While President Teddy Roosevelt gets credit for a vast expansion of publicly held lands and parks, it was Ulysses S. Grant who, thirty years earlier, had signed a law protecting Yellowstone and its environs that began the movement of common conservation of great places. They have all lured me with my vain attempts at understanding spirituality and delusions that we will all come to see the folly of our differences when we stand on the great canyon’s rim or stare up the face of El Capitan in Yosemite or ponder the desert floor through “The Window” of Big Bend National Park. There is no denying, for me, that I am psychologically altered in the presence of natural wonders like the Rocky Mountains or motorcycling across the Great Basin or sleeping in front of the dunes at Padre Island National Seashore. The change might be emotionally subtle and hard to define, but it is real and present; I just do not have a name for it.

My consistent returns to the Grand Canyon have involved several rim-to-rim hikes over the 24-mile distance and, on three occasions, I ran the route. R2R runners were a rather small and exclusive club for several years until the emergence of a new endurance phenomenon referred to as R2R2R. Yes, athletes attempt to run from the South Rim to the North and then back southward to finish where they started within 24 hours. The inverse nature of the effort, running or hiking, can be deceptive and even deadly because the 4,380 feet of lost elevation on the trail to the river makes the runner believe the trip is more manageable than they might have previously believed, but the 5,850 foot climb out can debilitate even the fittest. The canyon takes an average of 12 lives each year, usually from heat and dehydration, but hiking accidents and falls have put the estimate of total deaths at 770 since Maj. Powell’s reports of its grandeur began to be published and Americans were tempted by their country’s mostly untold story.

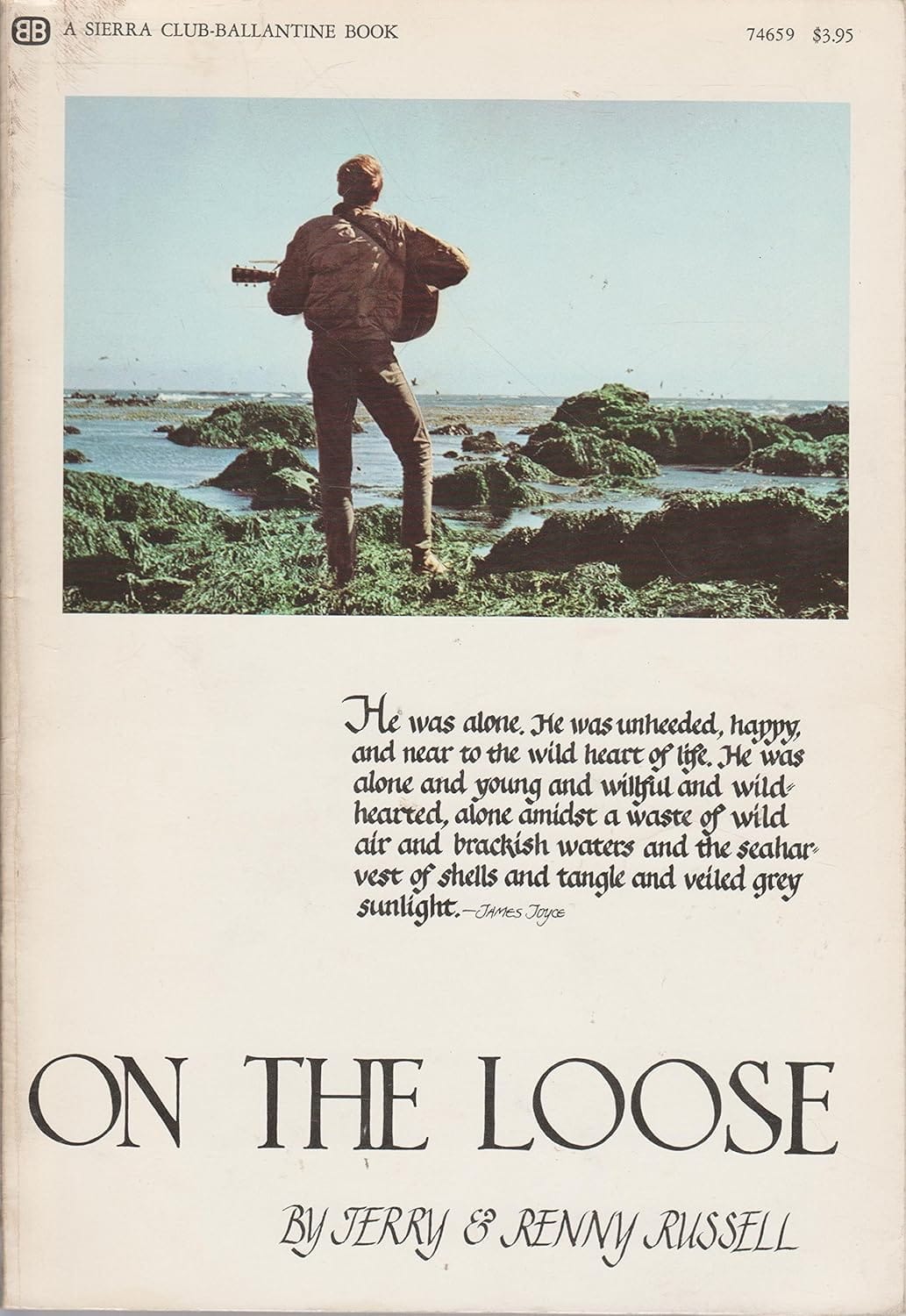

My wanderlust has been mostly innate but was refined by the discovery of a 1967 Sierra Club publication of photos and text in a book entitled, “On the Loose,” created by Terry and Renny Russell. The brothers were seeking solace in their youth by wandering deserts and seashores and hiking the Sierra Mountains. Their writing and photography made sleeping in rusted-out old cars and going hungry seem almost inspirational in a modest publication that sold millions without marketing. “On the Loose” was a love poem to the natural world and youth and brotherhood and hope, and the pages of my copy are worn and tattered after traveling with me through the decades. I can even find a private calm and serenity in the pages of that book after listening to Donald Trump babble his hatred and idiocies.

Nature can, in fact, cure even the most noxious of afflictions.