On the origins of Chile con Queso

Why do so many people seem to think that chili con queso is some Gringo abomination?

So I recently joined a Facebook group called I Can Cook Mexican and man, does it ever run the gamut. Some, maybe even most, of the members can indeed cook Mexican food that appears to be delicious, while others unashamedly display their very Midwestern takes on the genre, only to get lambasted by the peanut gallery in the comments for their troubles.

And it’s not just the whitebread folks — Texans, whether or not their name ends in a Z, can expect to get an earful from the Californians and New Mexicans on how dishes of ours like cheese enchiladas, fajitas, and chile con queso are “not Mexican.” It gets really heated, apparently, though most often by the time I arrive on the scene, most of the shit-slinging comments have been removed, leaving only admonitions to “play nice” and “everybody chill out” remaining behind as reminders of the online brawl I’d missed.

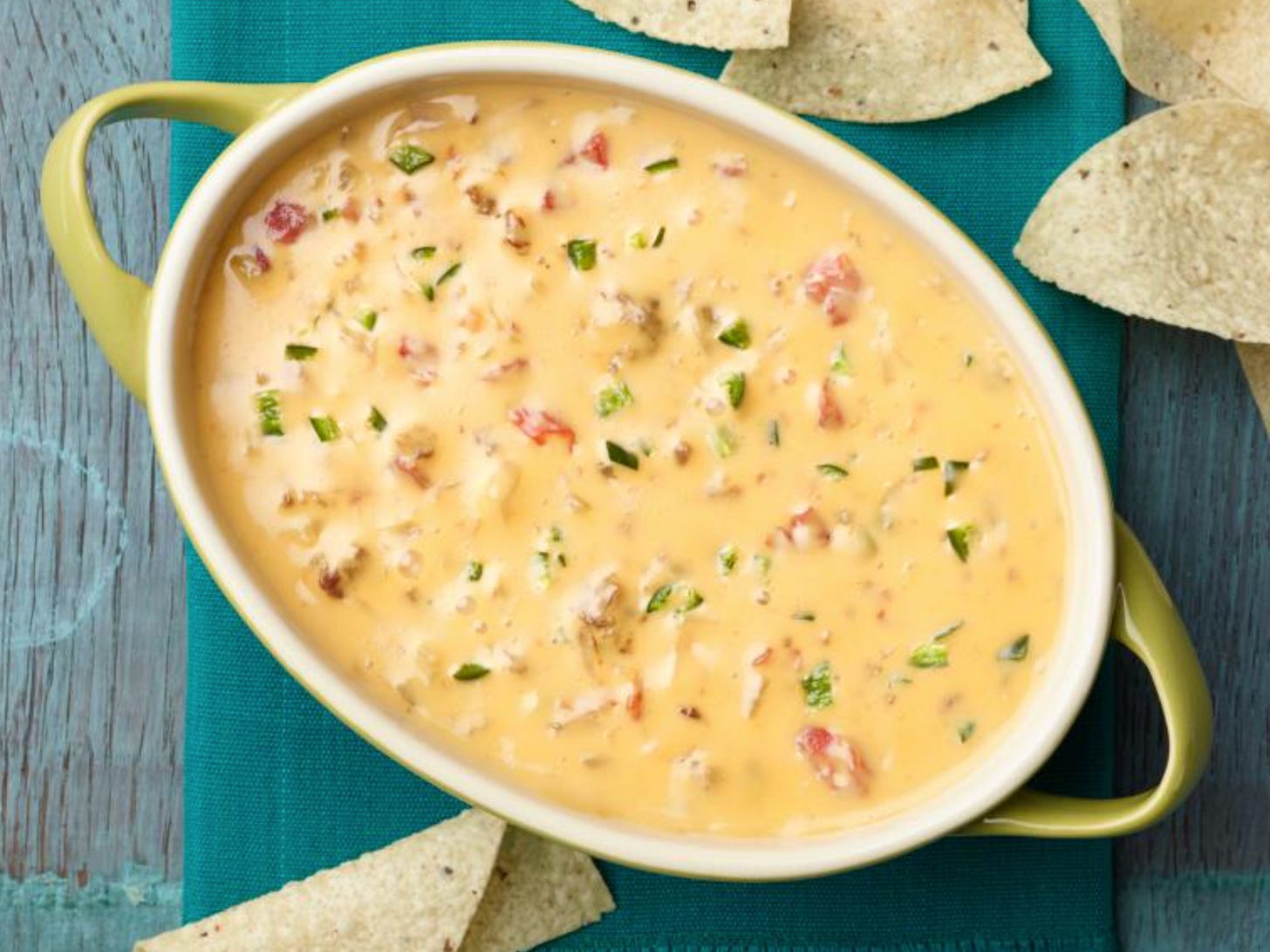

Such as one I missed today, this one on the authenticity or inauthenticity of chile con queso, or “cheese dip” as it was referred to in the original post. The verdict of a majority of readers there seems to be: NOT MEXICAN, TEX MEX AT BEST.

So I decided to dive in. As usual on such matters, the Homesick Texan is a good starting point. There were a directed to an excerpt from the cookbook Queso! by Lisa Fain. (Love the exclaimed title.)

Key moments in the timeline:

1816: The words appear in the Spanish-Mexican novel, El Periquillo Sarniento (The Mangy Parrot) by José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, though apparently without description.

1865: In “Glosa del Chile Verde con Queso,” an anonymous Mexican poet laments that modern-day women had lost the art of stewing chiles with cheese.

1887: Date of publication for the first recipe of a queso-like dish appears, though in the Mexican cookbook La Cocinera Poblana, it is listed as “Chiles Poblanos.” This does not mean queso-like dishes weren’t out there already, as we have seen. At any rate, this was a simple recipe calling only for cheese, poblano peppers, and tomatoes.

Even today, that’s a perfectly good bare-bones queso in my view. But apparently, something wasn’t quite right about because Fain goes on to write:

Although chile con queso most likely originated in Mexico, the first published recipe to use the phrase appeared in the United States. An 1896 article about Mexican cuisine in the magazine, The Land of Sunshine included a dish called Chiles Verdes con Queso, which was a mixture of long green chiles, tomatoes, and cheese. Like all early Mexican versions, it was intended to be a side dish, with the cheese enhancing the chiles, much like cheese melted onto cauliflower. Its evolution to a dip was yet to come.

Meanwhile, Fain continues, Swiss fondue and British Welsh rarebit were enjoying their first vogues over there in Europe and making their way to America. Each of these was considered a meal, or at least more of a dip than a side dish. You bathed toast or vegetables in liquid cheese rather than ate peppers enhanced with melted queso.

And so there came a fusion — “Mexican rarebit,” in which pepper pulp was added to milk, cheese, and egg and eaten over toast. Fain dug this up from a newspaper from Kentucky (of all places) in 1908. Around the same time, other recipes emerged replacing the pulped peppers with chile powders, and in 1914, according to Fain, the modern-day dish began to take shape:

Eventually, an astute cook realized that combining rarebit (and getting rid of the egg often used in its preparation) and chile con queso would make for a fine dish, which leads us to a recipe for Mexican rarebit that appeared in the 1914 edition of Boston Cooking School Magazine and that called for green chiles, tomatoes, cheese, beer and corn. This version, though intended for pouring over toast, was very close to what most would consider American chile con queso today.

However, the dish may well have been on the menu at O.M. Farnsworth’s Original Mexican Restaurant in San Antonio as early as 1900. In 1922, he told an interviewer the menu was unchanged since he opened 22 years previously, but there is no proof one way or another about that claim, nor what that queso of his looked like.

Fain believes the dish’s big break came through its inclusion in The Woman’s Club Cook Book of Tested and Tried Recipes, a perennial volume published in the early 1920s in San Antonio. Here the dish was prepared similarly to today — no egg, American cheese explicitly called for, and intended for use as a dip with tostadas (or other hand-held Queso Delivery Systems). It was also described by the name we use today, and the only difference was the recipe called for cayenne and paprika instead of serranos or other fresh or dried and pulped or ground peppers. While it would take years to be anything other than a regional dish — mainly confined to Texas, New Mexico (where they used white cheese from Chihuahua), and parts of the Midwest — until roughly the 1980s, when chain restaurants from this neck of the woods carried queso to the world.

Fain probably wrote her history before the advent of newspapers.com, and while nothing I was able to find in there disproves the broad arc of her her thesis, some items fill in some holes and open up new avenues for exploration.

It appears to have first made its way into newspapers in exactly 1900, when we find references to both chile con queso and chiles verde con queso in newspapers in Visalia and Napa, California, respectively. In the latter example, a Napa restaurant offered chiles verdes con queso but not as a side, as Fain’s theory speculates, but as a main dish, for it is offered at the same price (15 cents) as the other entrees on the menu, and with the same sides (bread and butter for all.)

So that would seem to me to possibly indicate that it had already taken on a stew-like consistency by that point, rather than the cheesy cauliflower-type dish she posits was the order of the day until the Welsh and the Swiss joined forces in their rarebit-fondue invasion.

And take that, Californians. Y’all started it. Maybe.

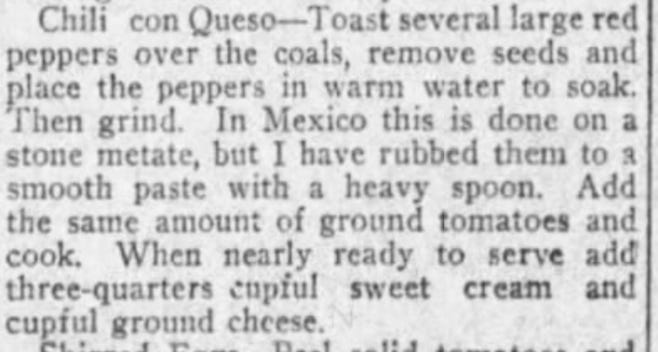

On Christmas Eve 1905, the Kansas City Star ran the following recipe under the heading “Dishes Prized in Mexico”:

Sounds pretty modern-day queso-ish to me. Evidently this anonymous cook saw this dish prepared in Mexico using the most authentic implements possible, so take that, you people who claim queso is not Mexican.

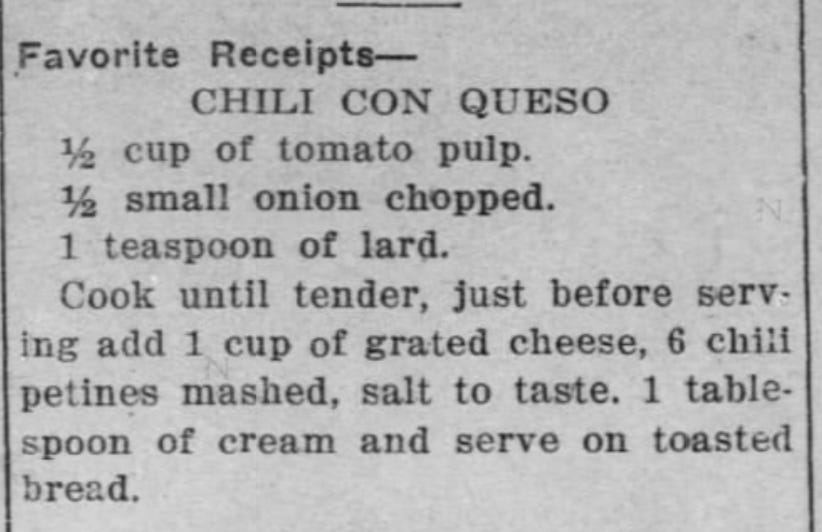

Here is another Kansas recipe, this one from the town of Concordia, year of our Lord 1915:

Remember, at the time, Kansas was very much bound to Texas as the trailhead for Texas cattle. Many times you find variations on dishes long popular in Texas in old Kansas newspapers, simply because Kansas was the more literate, refined state at that time, so more recipes made it into print, and there were more newspapers out there to be collected and preserved until today.

Which is not to claim a Texas origin for queso; just to say that’s why it probably caught on in Kansas around the same time it was landing on menus and in cookbooks in San Antonio.

In 1920, a Chicago reporter visiting an authentic Mexican restaurant in Los Angeles reported seeing “chile con queso” on the menu though he didn’t elaborate. How authentic was this place? You could also order up half a baked sheep’s head. “It looked extravagantly uninviting to me,” wrote our Anglo correspondent.

So again — we find a dish by that name in an authentic Mexican restaurant in gasp, Los Angeles, California.

As to how it has come to be known as some bastardized White Man’s Tex-Mex concoction — well, to me, that’s a better question than whether or not it’s truly Mexican. It certainly seems puro Mexicano to me.

Epilogue: It would not be a deep-dive into the origins of a Mexican dish if I did not stumble into an example or two of cringeworthy racism, some of it of the paternalistic romanticizing variety, others more virulently hateful. This one is a little more of column A than B, but given the tenor of the times — with Black Jack Pershing’s foray into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa still fresh on everyone’s minds — there’s a little of the latter implicit in there too. (From the Baltimore Sun, Cinco de Mayo 1920):

Now wait a minute, according to 23andMe, I am only ten or so percent anything that could be generously described as Latin — Cajun, mainly, with a tiny strain of Iberian and a minuscule one of possible Native American — and that “father of comets, sea serpents, misshapen giants, juggernauts and a thousand other monsters” was far more apt to arouse in me stormy passions rather than paralyze my senses. I guess Herradura had a way of invariably finding its way to trigger the combined .75 percent of my genetic code that is Latin-Indian.

I mean, you gave me brown liquor and I’d become morose. But put a bottle of tequila in front of me and like as not this was me by the end of the night: