Roads Unridden

When someone leaves our lives in an untimely manner, we look for signs from them that they are OK, that they hear us. I've never really accepted such ideas, but I had just ridden my late pal's bike through a hard rain squall and was soaking wet as I stood by the road and spoke to an invisible soul.

“Think of where man’s glory most begins and ends, and say my glory was, I had such friends.” - W.B. Yeats

I have always thought of the road as a kind of curative. Instead of running away from problems, I have had the sense that I was moving toward solutions, even healing. That was my central emotion when I left home on my first hitchhiking trip at age seventeen and went to see the West. When anyone stands at the rim of the Grand Canyon and casts their eyes across the ancient geology they understand more intimately our lives are small and transitory, and problems that seem insurmountable can feel minute. Those intuitive reactions also make every minute more precious. Just being in the world becomes an immeasurable gift.

My most frequent road trip is into the Trans Pecos of Texas. Riding the motorcycle up the switchbacks to the Chisos Basin or taking the long, winding run down Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive to the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon and its almost 1500 foot walls. The River Road, which is Ranch Road 170, from Study Butte to Presidio, is nearly intoxicating to a motorcyclist as it runs along the Rio Grande and climbs up what the locals call, “The Big Hill,” believed by riders to be the highest elevated stretch of highway in Texas. The River Road courses past improbably large mesas and through several geologic ages written in the layered rock. I am always better after I have rolled those miles, and even writing of them makes me happy.

There are Texans, mostly male, whose fascination to the region of the giant National Park is connected, at least partly, to the movie Fandango. The 1985 film was Kevin Costner’s first released starring role and involves a last road trip to Big Bend by five college friends facing the draft of the Vietnam War, marriage, jobs, and looming adulthood. Their goal, before leaving the University of Texas, is to dig up “Dom,” a magnum of pricey champagne that they had previously buried beneath a rock atop the River Road’s “Big Hill.” They find Dom, and do a final toast to celebrate what they describe as “the privilege of youth,” and then, eventually, move off to different destinies.

The “Dom” Rock Toast in Fandango

Fandango has become a cult classic and has led to frequent tours of locations in the Trans Pecos where various scenes were filmed. There are still fans of the movie who emulate the youthful pilgrimage and travel the River Road to find Dom’s historic burial site. I have been there many times, not to search for Dom, but to stare at the Rio Grande and how it twists into the distance, invisibly carving rock and deepening canyons. I had been planning a Dom excursion for over a year with a friend who was determined to go back to the spot made famous in the movie.

“I’ve only been to the park and that area once,” Wade Goodwyn told me. “But yeah, the movie was a part of that trip back when I was a young guy.”

“Well, let’s get out there,” I said. “You’ve got your new bike. It’s perfect for the long ride.”

“Yeah, I’d like to.”

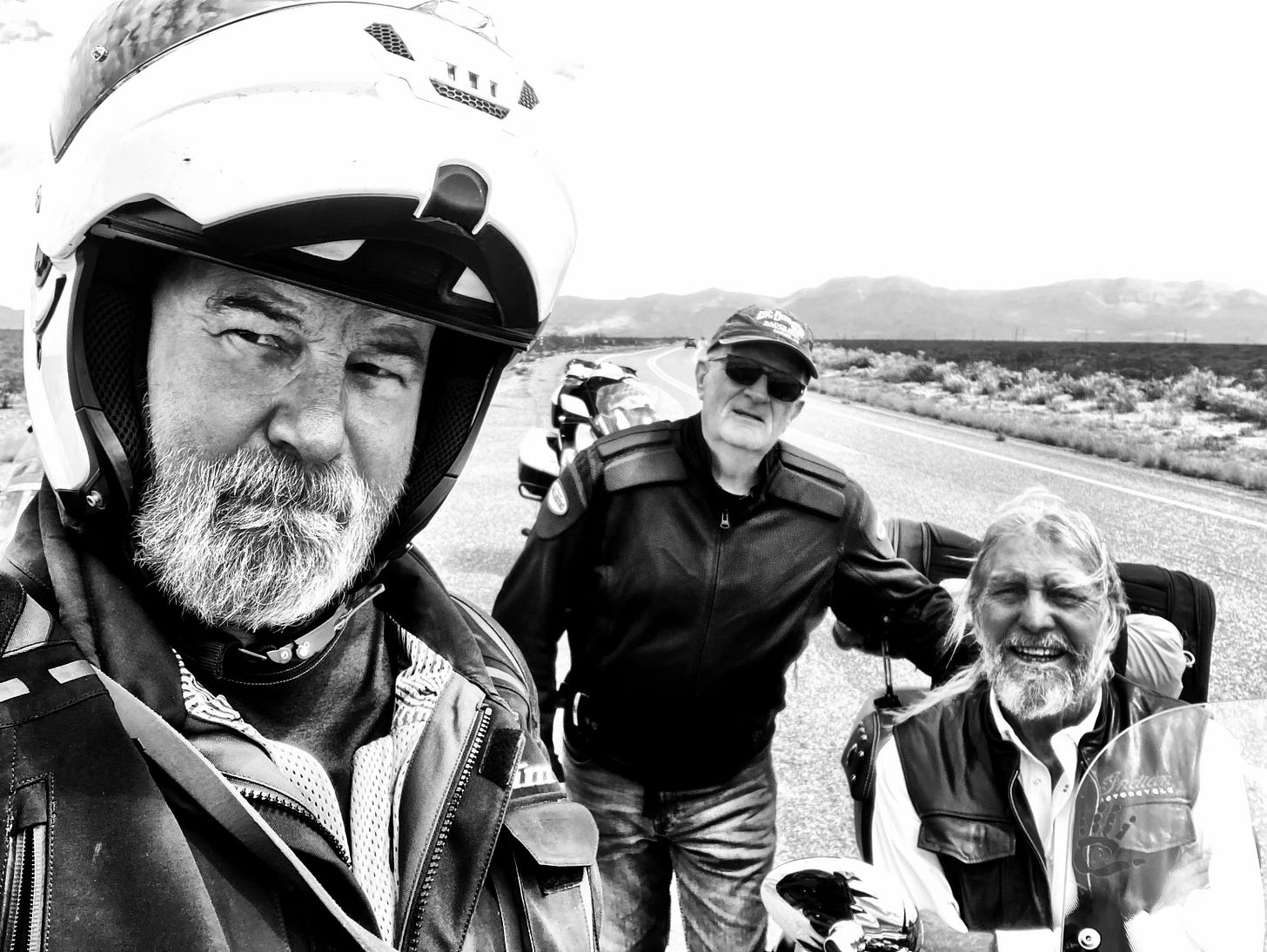

Wade had recently returned from traveling to Colorado. He had trailered his big six cylinder BMW GTL motorcycle out west from Dallas and had spent a few days riding and leaning into Rocky Mountain curves with one of his oldest buddies. Wade and I had made two attempts for him to find a way to get to the Big Bend but he had cancelled at the last minute because of his health. On our third try, he was so determined he booked a house where we would stay with two of my other riding pals while we all took spins down to Terlingua and around the Davis Mountains Scenic Loop and back into Marfa.

We were sitting at the Jersey Lilly restaurant in Hico, Texas, having a few beers, Mexican food, and talking politics, broadcast journalism, writing, Texas history, literature, and, of course, motorcycles. I knew Wade’s health had faltered when he canceled the second trip. I had asked him if he was okay in a text message and he had answered with only one word, “Cancer.” I did not know the type or its degree of seriousness until we met that afternoon in Hico.

“That bike’s gonna be yours, my friend, before too long,” he said.

“What are you talking about?”

“Well, it’s pretty simple, Jim. I’m dying. I’m hanging on as long as I can, but I won’t win.”

My response was awkward, but I did not know what to say. I assumed he did not want to talk in detail about his situation and was just trying to live well with what time he had remaining. I did not want to accept what he was saying, either.

“I don’t mean for this to sound flip, buddy, but aren’t we all dying? It’s just a question of the rate at which we depart, no?”

Wade laughed. “Ha, you’re right, but I can pretty much assure you I will beat you across the finish line. And that’s when you will get my motorcycle.”

“I’m sorry, Wade. I don’t know what to think about what you are telling me, or even how to respond, and prefer not to think about such a thing.”

“It’s okay. Let’s have another beer and some more chips.”

I recall that I initially met Wade Goodwyn at the Branch Davidian standoff in Waco when he was a freelance reporter for National Public Radio (NPR). We spoke briefly a couple of times during our 52 day covering that tragedy, and then worked related stories at the Oklahoma City bombing and the trial of convicted terrorist Timothy McVeigh in Denver. We never spoke more than a few sentences in passing conversation but we kept running into one another at hurricanes and a few political stories. Although I never got to ride with him, our nascent friendship grew out of a mutual love of motorcycles, and the written word. We were planning several trips, and I had told Wade of roads I had ridden that I knew he would enjoy and a few new ones I had yet to reach. Our goal was to take some weeks and do a tour of the American West on our bikes.

When melanoma silenced his great voice, Wade had been retired only a few months from his three-decade career with NPR. I had sometimes entertained the thought that his baritone was what the U.S. might sound like if it had a singular voice. His radio reporting narratives were assured, authoritative while also engaging the listener with his writing and the natural resonance and timbre of his spoken words. His wife, Sharon Sandell, a determined and accomplished pediatric ICU expert, extended her husband’s life by several years with her capabilities of managing a fraught healthcare system, but Wade’s time ran out.

"When someone leaves our lives in an untimely manner, we look for signs from them that they are okay, or that they hear us. I have never really accepted such ideas, but I had just ridden The WG through a hard rain squall and was soaking wet as I stood by the road and spoke to an invisible soul."

When Sharon contacted me after his passing, she wanted to make arrangements for me to come pick up his motorcycle. I told her that was not necessary and that I am sure Wade had other intentions for the bike. I offered to help her sell it, which was not a notion she was willing to accept.

“That model BMW is worth a lot of money,” I said. “I’m sure I could get you a top offer.”

“No, you don’t understand. Wade insisted you get his bike. It’s one of the last things he told me, to make sure I get it to you. And because he insisted, I insist. He knew you’d appreciate it more than anyone.”

“I, once more, don’t know what to say.”

“You will make me, and Wade, very happy, if you take his bike and ride it. Please make your first trip to Big Bend, and I hope you will have a conversation with Wade when you get out there, and then I hope you will ride it to all those places you and he talked about going together.”

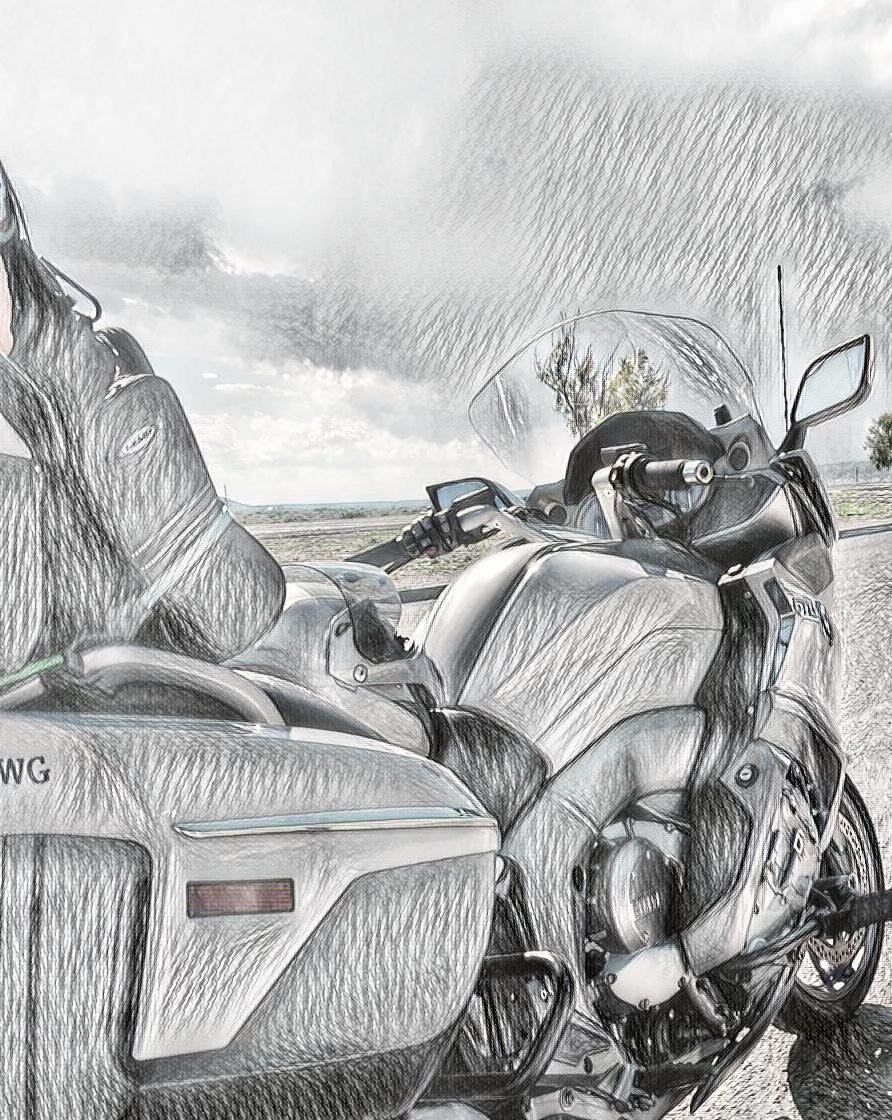

Those are the reasons I find myself in Show Low, Arizona, riding Wade Goodwyn’s BMW K1600cc luxury touring motorcycle around the West. I had promised Sharon I would place his initials on the bike and they are clearly visible on a saddlebag as I motor over mountains and across deserts, up to the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley, and maybe down to the Great Basin before going back to Texas. I am not one to name inanimate objects but this motorcycle is now known as “The WG,” and it will always carry those two letters.

The Mogollon Ranges, New Mexico

Before meeting up with my two current riding pals, Chris Greta and Danny Self, I stopped by the side of U.S. 385, leading south to the national park. I chose a spot inside the Sierra Madera Astro Bleme, a term that translates to “star wound.” A meteor slammed into that part of Texas untold millions of years previous and left a crater surrounded by an upthrust of mountains. The location has always spoken to me of eternity, and was the logical place to stop and thank Wade for his gracious gift and fleeting friendship. I admitted I was not sure I believed in what, if anything, comes next after life, and that it may always be unknowable, but I was hopeful he might see the roads and the rolling landscape through me, and that maybe, that way, we can still share the ride.

Gila National Forest, New Mexico

When someone leaves our lives in an untimely manner, we look for signs from them that they are okay, or that they hear us. I have never really accepted such ideas, but I had just ridden The WG through a hard rain squall and was soaking wet as I stood by the road and spoke to an invisible soul. Any passing driver might have thought I was daft, wandering in the drizzle and talking to myself under the sky still dark with rain clouds. When I finished speaking, though, and had remounted the motorcycle, I looked over at one of the distant ranges on the edge of the Astro Bleme, and it suddenly caught the long light of a settling western sun, and lit up brilliantly as I rode off.

Be sure and subscribe to receive our stories weekly.

If you can, we'd love it if you'd become a paid subscriber.