The Guns of October

“Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war than we know about peace, more about killing than we know about living. We have grasped the mystery of the atom and rejected the Sermon on the Mount.”― Gen. Omar N. Bradley

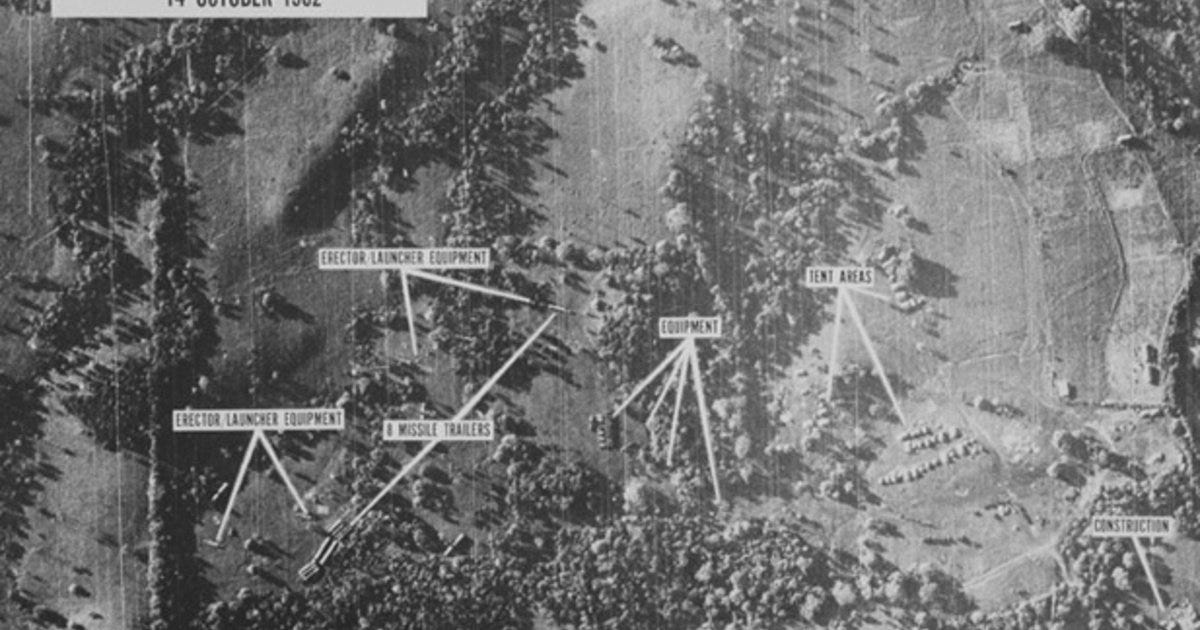

(If you are reading this on the day it was dispatched, Oct. 16, 2022, it is exactly sixty years to the day from the beginning of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Those of us who lived through the 13 tense days, even as children, wondered if civilization was about to be rendered non-existent through the deployment and use of nuclear weapons by the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The U.S.S.R. had begun emplacement of Intercontinental Ballistic Missile silos on the island of Cuba, just 90 miles from Florida’s coastline. President John F. Kennedy addressed the nation on my tenth birthday, and I watched on TV and wondered if I was to ever live to adulthood. This newsletter addresses that experience, and how the threat of those days has never ended. - JM)

Editor's note: An audio version is available of this story via the player below or through your preferred podcast provider.

Our little elementary school was new and had begun teaching lessons unique to history. We were the first generation to confront Armageddon in our childhoods after the detonation of a nuclear device in Japan. What war had unleashed on the world was suddenly being inserted into our psyches. The fact that we became known as “boomers” was as ironic as it was logical, and more than three quarters of a century later, we are still living with a nameless, shapeless dread we try to not acknowledge.

McGrath Elementary was set back in a grove of trees between expanding housing developments in the suburbs of the automotive industrial centers. I can still smell the fresh paint and see the shining metal trim on the windows and how it seemed to almost glow even on the innumerable gray Michigan days. While we were just grade schoolers, we felt the great sense of optimism and growth potential in our communities. We were surrounded by construction crews putting up bungalows and ranch-style homes built with mortgages guaranteed through a program created by the federal government to help veterans of the war begin their lives.

In our classrooms, the desks we had been provided had attached chairs and glassy Formica tops and our books bore stiff bindings with rich paper and ink smells. I loved school as a boy, and I was especially happy when there were deviations from daily lessons. Consequently, I was excited when a teaching assistant rolled a film projector into the back of the room. A screen was pulled up and hooked on a three-legged stand and Mrs. Hagemeister began to act very serious. After the projector had been plugged in and the screen scooted to the front of the classroom, our teacher spoke to us in a tone of voice I had not heard all year.

"Class, you are about to watch a short film from the government,” she said. “But you should think of this as a learning opportunity to understand a bit about the world and it might be more important than anything I can teach you."

Immediately, she had our attention. We also got a sense that we were to be a part of something important. My teacher’s words excited my imagination and I thought we were on the verge of opening a magical door that was a privileged entrance offered only to schoolchildren. My eagerness, though, was smothered in a generational darkness, which still hovers over every human aspiration.

"Children, you all know already about war. Many of your fathers haven't been back from the war for much more than a decade. There are always people who start wars, and we must be prepared. That's what you should be thinking about when you watch this movie. How to be ready if you face the unimaginable."

I remember her words as clearly as if she were across the room today speaking. Mrs. Hagemeister, matronly and tall with her hair born up in a net, walked silently to the wall switch in the back of the room and turned off the lights. The administrative assistant from the principal’s office clicked the toggle on the projector to cast a cone of light toward the screen. We listened to the whirring of the un-spooling film on spinning sprockets and watched the leader count down. There was a title on the screen that I don't remember exactly, but I think it referenced school safety in the nuclear era. A formal male baritone made vague references to politics and government disagreements and powerful new weapons in the world.

I lost track of what the narrator was saying and was drawn into the strangest scenes a child might have ever encountered. A classroom of students just like ours was shown taking instructions from their teacher, who told them to do something like "drop, roll, and curl" under their desks. A siren wailed in the background and then there was a mushroom cloud rising darkly from the earth. Children scurried away from windows, tipped their desks on the side, and assumed a fetal pose as a tumbling wave of destruction raced across the landscape. I did not sleep much for many days, and a half-century later, many nights, I still do not. Neither I, nor anyone else, is more protected from nuclear holocaust today than we were when those traumatic films were premiered to my generation.

In a few weeks, we had our first nuclear safety drill. Students had been told that if the fire alarm blared without interruption, instead of pulsing, it was a bomb warning and we were to “assume our safety positions.” Over the course of the next few months, we scrambled to overturn desks and get into our fetal poses, and always during class time. No one had ever considered the mushroom cloud might arise as we were walking between classes and how that might cause chaos and panic. Of course, none of our new ritual was likely to make any difference or save a single life. We would have been doomed before any alarm sounded.

The nukes are more powerful now and can destroy entire nations, not just cities. Another tyrant, whose finger is on a deadly button, can change the course of human history, maybe even write its conclusion. The American president seems to be trying to convince himself that the Russian dictator is a “rational actor,” but the wanton civilian deaths and torture and atrocities committed by his army indicate no remorse or strategic value beyond terror. The basis of the deadly dispute is as old as war itself and revolves around territorial claims, natural resources, and a difference of historical and cultural perspective. After the cumulative carnage, negotiated settlement appears impossible, and humans continue to live with the same fear that has haunted us since we first split the atom.

The compounded risk of geopolitics is no longer just about the potential use of a nuclear weapon. Governments have taken comfort in the textbook notion of deterrence through a concept analysts dubbed “Mutually Assured Destruction,” the idea that there is no desirable outcome in a nuclear conflict because both parties would be destroyed. When one nation fires off a nuclear weapon, the other reacts with an equal response, and the devastation continues to elevate. In the unlikely event anyone survives the initial explosions, radioactive fallout drifting across the globe will kill them with cancer and the destruction of cell tissues. What point would there be to live in such a landscape? To start humanity anew, and repeat the process? What evidence is there we have learned to avoid war? We started clubbing each other on the head in disputes over animal carcasses when we came out of caves and later began dying to defend our imaginary gods, and then to acquire power and control over resources and huge populations. In motives for war and killing, humans are ingenious.

During my boyhood, when the world was learning to live with the monster it had bred and let loose, our family of six children and two adults lived in an 825 square foot house in a lower income neighborhood comprised of a Dixie Diaspora. We were uniformly white transplants that had come up from the South, escaping from farms to work in the car and steel factories. There was no time to worry much about nuclear weapons when you were a laborer with a large family. The electricity bill was of greater concern than international politics.

Our house, improvidently, had been built in a flat spot under the approach to the airport and at night as I lay in bed I heard the prop-driven airplanes feathering their engines to land. I never noticed the subtle changes in sound until I started watching the war movies that began showing up on television. I looked closely when the cameras showed airplanes on bombing runs. Not too long after the bomb bay doors had been opened, just as the weapons were released, there was a reduction in the plane's power, which I later learned was to avoid drag on the weapon, keep the aircraft longer over the target, and to improve sighting.

A kind of silence hung in the air, which reminded me of the passenger planes passing over our house as they neared the runways at Bishop Airport. The movies and the newscasts about Russia and film of the nuclear explosions in Japan convinced my impressionable mind that every plane over our house feathering its props and power was a Soviet bomber that had slipped undetected across the Canadian border and was about to drop a deadly explosive into our hillbilly neighborhood. Plus, we lived close by a manufacturing facility known as the Tank Plant, which produced thousands of Sherman Tanks during the war and had been converted to automotive assembly. Surely, I told myself during my agonized nights of sleeplessness, the Russians would want that plant bombed out of existence.

"I'm scared, Ma," I told my mother one groggy morning.

"What about, son?"

"The airplanes at night when I'm in bed. They might be carrying bombs from the Russians."

"Oh son, that's nothing to worry about. Nobody will drop a bomb here."

Ma was wrong when I was 8 years old, and anyone who thinks that way today is even more mistaken. Russia is not the only dangerous state actor. North Korea, once a signatory of the global Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), has begun firing missiles over Japan and is implying it is a precursor to an emerging thermonuclear arsenal. As the U.S. struggles to reinstitute a restraining nuclear agreement with Iran, the Ayatollahs manage to keep a political haze over their current armament productions. American diplomacy does not recognize a right in Iran for nuclear weapons while Israel, a nation that has never even acknowledged a nuclear arsenal, is believed by defense analysts to have the fifth largest in the world and has refused to sign the Non-Proliferation treaty. Israel’s Dimona Reactor in the Negev Desert has been online since the sixties.

Iran says it has a sovereign right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and Israel says it does not trust Iran's unstable leadership and will take appropriate measures. America makes vain attempts at mediation but where does any country's moral authority originate when it has deployed nuclear weapons, still has an arsenal, and is telling another sovereign nation that it cannot develop similar armaments? No one has ever answered this question. Iran also wants to know why Israel is permitted by the world community to have nukes while Tehran is told no. Does not one sovereign nation have the same rights as another sovereign nation, regardless of the form of government its citizens have enabled?

Pakistan and India, sharing a border and contempt for each other, have also refused to be signatories of the NPT. Israel, Pakistan, and India felt geo-political threats and developed nuclear weapons as deterrents, which are the aspirational goals of the powers in control of Iran and North Korea. Of course, it is possible they have evil intent. How can the actions of Russia’s leadership in the Kremlin be inferred as anything other than malevolent?

Non-proliferation is not a solution to nuclear danger. Only the destruction of arsenals can save us. Deployment implies use, and manufacture is a political statement. There is no possible need for nuclear weapons. Their global elimination is essential if humans are to continue evolving, even existing. The entire planet needs to sign an irrevocable treaty mandating the disassembling and disposal of nuclear bombs and missiles. No other solution is even remotely hopeful.

We are exactly sixty years removed this October from the first nuclear standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, a geopolitical conflict that arose when the communists began to move missiles into silos on the Island of Cuba. President Kennedy and Premier Nikita Kruschev were at distinct disagreement over the USSR placing weapons in the Western Hemisphere. JFK launched a naval blockade to prevent the delivery of the missiles, and at least one ten-year-old boy stared in silent fear at a gray, flickering television, learning the forms of his future.

The tense confrontation was ultimately defused by sober diplomacy. Kennedy agreed not to invade Cuba and the Soviet leader acquiesced and stopped his plans for a missile defense of the island. Secretly, the American president also agreed to remove U.S. weapons from Turkey. Nonetheless, the nuclear brinksmanship was the closest humans had come to a nuclear apocalypse after World War II. We have returned, however, to the same dangerous political crisis between Russia and America, hoping logic prevails, not anger or power.

And I’m still scared, Ma.