The Plainsman

“I don’t know what y’all think,” Hightower said. “But here’s what I know. While we’re out here strugglin’ to make livin’, Ol’ Ronnie Reagan’s up there in the White House drinkin’ champagne and eatin’ caviar while we’re all down in Texas drinkin’ Lite Beer and eatin’ tuna fish.”

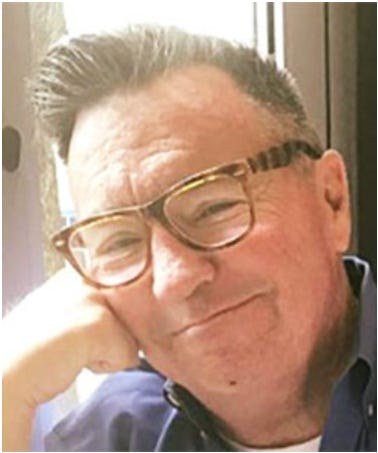

When he came down from the High Plains, there was no real plan. He told me years later that he wanted to be part of making a difference, but he was not sure how that might happen. I never understood what motivated people like him when his goal had such vagaries. Unfairness certainly seemed to keep his attention, and he talked often about politics and improving policies to help more Texans. I was not certain of his focus, but I knew quickly he was a good man. I still think there is something about the big sky and open country that forms a resolute and caring person. It shaped him, I know.

I met Pete McRae back in the eighties after he had left Amarillo for Austin and was venturing into politics and policy at the state capitol. Eventually, he found work with the office of the Texas Agriculture Commissioner. Potter County, where his hometown was located, is, historically, the most financially lucrative agricultural county in all the land. I always assumed that was why Pete had become employed by Jim Hightower, but I think the commissioner’s unapologetic political rhetoric also appealed to my friend. Pete spent a great deal of his time making certain that services were delivered to farmers and ranchers, but he also quickly became a political animal.

America was amid Ronald Reagan’s de-evolution and deregulation of democracy and Pete was drawn to Hightower’s defiant voice. I remember a speech the ag commissioner gave during the Californian president’s second term in the White House. There was a large crowd assembled on the south steps of the Texas capitol and Hightower had taken to the podium to do his best to disassemble support for Reagan. I had been talking to Pete earlier about Hightower’s ascent on the Democratic fund-raising circuit and we were standing next to my TV camera as he spoke.

“I don’t know what y’all think,” Hightower said. “But here’s what I know. While we’re out here strugglin’ to make livin’, Ol’ Ronnie Reagan’s up there in the White House drinkin’ champagne and eatin’ caviar while we’re all down in Texas drinkin’ Lite Beer and eatin’ tuna fish.”

The crowd howled, and Pete looked over at me and smiled. He knew enough about my business to know that I had part of my sound that evening for the TV station’s evening newscast down in Houston. These were fulsome times for Texas Democrats. On Election Day in 1982, every statewide office had been won by a candidate with a D next to their names. Mark White, a Houston attorney, had become governor, Bill Hobby, whose family owned the television station where I worked, was Lieutenant Governor, future governor Ann Richards had been elected the state treasurer, Jim Mattox, a former congressman, was attorney general, Garry Mauro, land commissioner, Bob Bullock was reelected as comptroller, and Hightower, who was neither farmer nor rancher, held the ag commissioner’s job, and was Pete’s employer.

The newly elected Texas Democratic officeholders were selling to voters what Hightower called “a ragin’ democracy,” even though no one was quite sure what it all meant.

On Inauguration Day, all the Democratic officeholders linked arms and walked toward the north entrance of the capitol building. They were followed by thousands of their supporters, confident, I am certain, of making Texas a liberal and progressive state that was good for business and still able to offer services for the disadvantaged. Most Democrats at that time, though, were relatively conservative. I ran around with my cameraman interviewing these energetic and optimistic voters who were convinced Reagan’s politics were not going to “trickle down” on Texas. The newly elected officeholders were selling to voters what Hightower called “a ragin’ democracy,” even though no one was quite sure what it all meant.

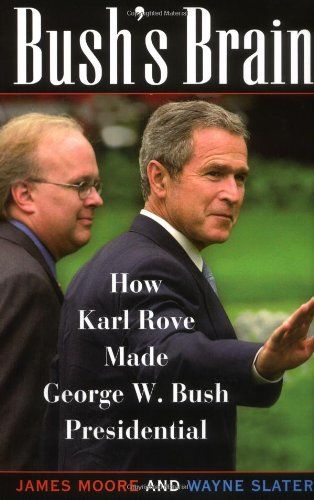

One thing it did not mean was that Democrats were assured to retain political control of Texas. On a limestone ledge above Shoal Creek in Central Austin, a Republican political consultant, ingratiating himself to the Bush family, had set up a shop. Karl Rove’s intention was to get noticed by raising money, and in the days before computer hard drives, he hired college students to keypunch addresses into magnetic tape with names of subscribers to magazines that sold gold and expensive luxury items. He built fund-raising lists and recruited candidates to run for office as Republicans, a wholly unsavory notion under the Democratic Lone Star.

Pete McRae, meanwhile, was working long hours traveling the state for the ag department of Texas. His tasks varied, but he listened to needs and suggestions from farmers and ranchers and took that information back to Austin to help refine or formulate programs that did a better job of serving the state’s agribusiness community, and especially the family farmer and rancher. He also delivered services to various ag organizations and businesses. Pete worked closely with Deputy Agriculture Commissioner Mike Moeller, a rising young Democrat who was able to manage the administration of the department while Hightower’s profile continued to grow as he traveled on the national Democratic political circuit.

Rove remained, in the meantime, busy with his intrigues and deceptions. Working for Bill Clements’ campaign, the first Republican governor elected in Texas since Reconstruction, Rove summoned reporters to his office to show them a wireless microphone hidden behind a painting on his wall. He expressed his conviction that Democrats had bugged his office to get info on their campaign, which later proved to be nonsense. An FBI report subsequently uncovered showed that the microphone had a broadcast range of only a few hundred feet and a battery life of just eight hours. Anyone listening had to be in Rove’s isolated parking lot and would need to sneak in to change the battery every night. The ruse was to set up a distraction from a debate between his client, Clements, and Mark White, which was scheduled for the next evening. Rove appeared to steal the idea from a Richard Gere movie, Power, which was about a failed political consultant who used the same bugging stunt. The film was released early in 1986 and in the fall of that year Rove was trying to get Clements back into the governor’s mansion. He probably kept his ticket stub.

An FBI agent named Greg Rampton, implicated in the microphone con, later appeared to be coming after Pete McRae’s boss, Jim Hightower. The day in 1989 that the Democratic ag commissioner was in Amarillo announcing his reelection campaign for 1990, Rampton showed up in his state offices with subpoenas for a long list of documents. The agent seemed to have a predilection for disliking Democratic officeholders and later spent nine months in Land Commissioner Garry Mauro’s agency building, copying documents and removing files, which garnered no incriminating evidence. The same turned out to be the case for Hightower and every other Democrat pursued by Rampton over the course of almost two years.

The publicity of the FBI investigation of Hightower, however, helped Rove’s candidate for the ag office, Rick Perry. A Democratic rancher from West Texas, Perry had made a high-profile jump to the Republican Party as Rove continued to build his consulting roster of candidates to turn Texas into a GOP state. His effort was complemented by Ronald Reagan, who managed to carry the bellwether political region of conservative Democratic East Texas. During a campaign swing he had invited voters there to become “Reagan Democrats,” an offer widely accepted, and which made the transition to the GOP easier in subsequent elections. Nonetheless, Hightower’s populist approach made him a formidable incumbent and Perry’s task, even with the backing of the agriculture chemical companies and corporate farming interests, was, initially, given long odds.

Until Rampton and Rove found their mark.

They accused a friend of Hightower’s, Bob Boyd, who was a consultant for the Texas Department of Agriculture, of raising funds for a political action committee while on state business. The money was allegedly going to be used to help elect Mike Moeller agriculture commissioner after Hightower left office. As specious as the allegations were against Boyd, Rampton claimed Moeller and McRae were aware of his endeavors and helped facilitate the collection of cash. Both men denied any knowledge of Boyd’s actions, and when he was informed of what might be transpiring, Moeller directly ordered the consultant to stop any activity even remotely related to politicking while on state business. Rampton tried to make the case that Boyd was being offered consulting contracts in exchange for the funds he raised, which was never proved in court.

There were consequences, though. Regardless of the lack of hard evidence, Boyd, Moeller, and McRae were convicted of doing something they did not do, but which happens daily in Texas politics. Perry defeated Hightower, later became governor, and he and his senior staffers raised millions while traveling on state business and attending political fundraisers during after-hours. Nobody, in fact, has ever been better than Karl Rove at using taxpayer-funded government travel to raise political cash. When considered in the context of how Rove has corrupted this country’s national electoral process with dark money, corporate cash, bundled funds, and political action committees that barely report, including donations from the ultra-rich, what Boyd, Moeller and McRae were accused of doing is almost quaint by comparison. Unfortunately, Moeller and McRae were sentenced to eighteen months in minimum security facilities while Boyd was granted leniency because of his age and health.

Greg Rampton, who seemed unable to abide even the notion of Democrats holding office in Texas, finally caught the attention of a federal judge in the state, who wrote the DoJ and asked for the agent to be reassigned. He was sent to Idaho, and later was involved as an agent and investigator in the shootout at Ruby Ridge. When the FBI was gathering evidence to convict separatist Randy Weaver of killing an agent in the conflict, Rampton rearranged shell casings to stage an incriminating photograph to offer the prosecution. The admission, a revelation in Weaver’s murder trial, cost the federal government the conviction, and he paid a fee for nothing more than violation of parole. Weaver had, however, lost his wife and son in the shootout. Rampton’s pernicious behavior had once more contravened the cause of justice. Weaver sued the federal government, along with his two surviving daughters. They received a million dollars each and he was granted a $100,000 judgment.

Pete McRae was nobody’s victim, though. His Irish soul would not be beleaguered. As Rove was politically manipulating George W. Bush to the Texas governor’s mansion and then the White House, McRae was rebuilding his life. Moeller went home to manage family ranches, but Pete was starting over from scratch. In 1989, at the time Rampton and Rove began spreading spurious stories to reporters about Moeller and McRae, Pete and Mike approached me about a TV news series. I was unable to get the time or interest from my editors, but I added their shared documents to a file I had been building on Rove. After Pete had been released from what he referred to as “camp,” we interacted as colleagues and friends. He faced a slow and tedious process of finding business and politicians to become his clients, but he was taking certain steps to reconstruct his existence as a professional.

Pete’s consulting practice grew with deliberation and his clients included construction companies to politicians. His inclination, to me, always seemed to be to help. Getting paid for it was a bonus. Interns became a part of his operation, too, and he taught and trained them on how to communicate, give back, and facilitate change for the better, regardless of their endeavors in the future. He had long been interested in helping the disadvantaged and had previously assisted in putting together a summer camp for inner-city youth to experience the outdoors and discover the history of the Buffalo Soldiers of Texas, the African American troops who had been sent to the edge of western frontier to protect settlers and travelers.

I took off for the sky, traveling full time on Bush’s presidential campaign for a nascent television network. Rove had turned his primary client into a contender after two electoral wins for the governor’s office. I had watched his every visible, and some unseen moves, for Bush and Perry, and how he filled the Texas Supreme Court with business-friendly justices. I assumed Bush might find himself in the Oval Office, as blundering as he was with the English language and his complete lack of curiosity about anything more than baseball and his family. As national reporters on the press plane began to speculate about their potential book deals to write about the failed Texas oilman, I knew there was a more interesting story onboard, and that was the one I intended to pitch.

I went back to Pete and Mike when I landed a publishing deal for Bush’s Brain: How Karl Rove Made George W. Bush Presidential. They delivered more source material and offered frank interviews of what Rove had done to their lives for nothing more than political purpose. Their story comprised the book’s opening chapters and lent credibility to the subsequent narrative about a political consultant who did not care who he harmed if the results were that he won. After my co-author Wayne Slater and I were given an interview on The Today Show and fifteen minutes with Bob Edwards for NPR’s Morning Edition, the book climbed for a short stint to number one on Amazon’s lists and became a brief New York Times bestseller. Such an outcome was unlikely without the courage of McRae and Moeller.

Pete and I became close friends, and I grew to trust his judgment and honesty to the point that I employed him as a researcher and producer on my second book, Bush’s War for Reelection. We drove my truck across the country to California and Nevada to conduct interviews with the families of Iraq War soldiers whose lives had been sacrificed in Bush’s war for oil, and revenge against Saddam. In Truckee, California, we stayed at a nephew’s and Pete was surprised to learn there is little more glorious than sleeping outside on a deck beneath Ponderosa pines with the temperature in the mid-thirties in the heart of summer, and a spray of stars that appeared to be at arm’s length. Before we had driven back down the Great Basin and turned east toward Texas, Los Angeles producers had called and wanted to make a documentary film from the first book. Pete’s emotional honesty on camera gave the final production a bit of power and it premiered in the marketplace at Cannes and was supposedly the first production to sell out the Paramount Theater during the SXSW Film Festival. While a warm spring rain fell on Austin, people stood in a line more than three blocks long waiting to get in to see the film.

Pete and I worked together on more projects and spent long hours in his truck traveling to the Mexican border to help Texas communities in the Rio Grande Valley with economic development projects and crisis communications connected to immigration. As his company prospered, he hosted my wife and I and another colleague, the late Travis County Commissioner Richard Moya, and his bride, on trip to Santa Fe. This was the first chance I had gotten to know Pete’s wife, Angel, who he had met and married later in life. Our conversations on that road trip were about dogs and travel and art and people and, of course, politics, and the trip ended far too quickly. When he got back to work, Pete began pondering ideas to help young people find their way into the right roles in government, politics, and business. He later launched his personal project of mentoring, which he called Rising Lone Stars.

When his great heart stopped, Peter Thomas McRae was sleeping another night in only his sixty-fifth year. Health afflictions related to his kidneys and heart had burdened him for several years. I had no idea. Most of his friends did not. Pete was not the kind of person to trouble others with his problems. I found it odd that my friend had slipped away on almost exactly on the twentieth anniversary of Bush’s Brain, a book he had helped to make possible, and which he constantly reminded me he was proud to have contributed to its creation. He was even more pleased, he said, that it had stood up to the test of history, regardless of how much Rove tried to assail its reputation.

“You know, you get up in the morning and you do the best you can, and things don’t work out, it’s because of something out of your control. And that’s the way I feel about what happened. They just won that battle, the bad guys, that’s the way I characterize them, as the bad guys. It’s just time to move on.”

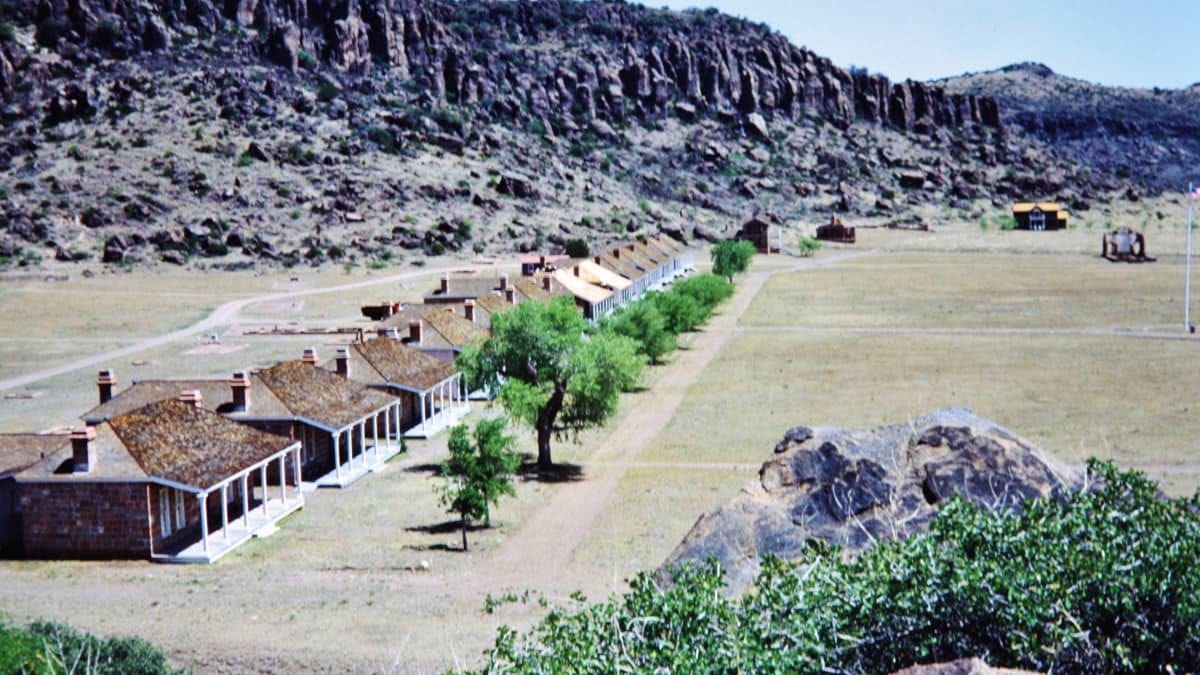

In the community center of Georgetown, Texas, the town where Pete and Angel live, his memorial this weekend was filled with stories from the progressive judges and mayors and lobbyists he had inspired and guided. His interns become lawyers and business leaders and liberal political consultants. They all spoke of his kindness and concern for their futures. I was thinking, as I listened to their praise of my friend, about my last interview with Pete as a news source to wrap up work on the first book. Constantly drawn as he was to the stories of the Buffalo Soldiers and their treatment, I encouraged him to travel with me to Fort Davis in West Texas to use it as a setting to close out the last chapter of Brain. The iconic fort is a national landmark and was the site of a great injustice done to a brave American soldier.

Pete had first acquainted me with the tale of Second Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper, the first African American to graduate from West Point. Although he had never drawn the parallels to Flipper, McRae certainly understood my interest in completing our interviews at the fort. Flipper, as a commander and quartermaster, was wrongly accused of stealing $18 from the U.S. Army after it was given to him for safekeeping. He had returned to his bivouac to find the money missing from the trunk at the foot of his bed. There was speculation Flipper was framed because he had been seen sitting on the porch of the general store with a white girl whose father owned the business. Because the money was in Flipper’s charge and remained lost, he was given a dishonorable discharge.

A century and a quarter later, Pete and I were walking across the parade grounds where Flipper had been betrayed by the country he had served, even though he was not considered an equal citizen because of his skin color. McRae, exactly like the Second Lieutenant, expressed no bitterness regarding how he had been treated. Both men had simply gotten on with their lives. In the mile-high air at the foot of the Davis Mountains, Pete appeared to enjoy the pleasant touch of the sun while talking about the Fort’s history. Only when pressured, did he return to questions about himself. He always considered himself the least interesting subject in his life.

“You know,” he said, “You get up in the morning and you do the best you can, and things don’t work out, it’s because of something out of your control. And that’s the way I feel about what happened. They just won that battle, the bad guys, that’s the way I characterize them, as the bad guys. It’s just time to move on.”

Which is what Pete did, by building a prosperous and helpful business, and revivifying his personal reputation, just like Flipper. McRae would likely say he is not worthy of comparison to such a man as the soldier, but they were both harmed by institutional and political unfairness. The soldier went on to become a successful surveyor for railroads in the American West, Mexico, and Europe. When he was posthumously pardoned by President Bill Clinton, and promoted to first lieutenant, a bust was unveiled in Flipper’s honor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Each year, an award named after Flipper is presented to the graduate who best exemplifies “the highest qualities of leadership self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties while a cadet.”

I remember after our conversation Pete and I drove north out of Fort Davis and up over Wild Rose Pass. Rolling down the mountainside, he mentioned the prairie expanse of the Permian Basin filling the distance. The stretch of land symbolized much of the promise of Texas. Oil flowed out of the ground there and filled the state with prosperity. George H.W. Bush started his own oil company in that part of West Texas. Coming home a war hero, he developed a successful production operation, and, eventually, became president. His son, George W. Bush, spent his childhood, playing baseball, and took his own failed turn at the energy business in that same landscape, which hovered for a few minutes in front of Pete McRae.

None of that mattered, though. This was also Pete McRae’s place. He was born in Texas. Lived his entire life under the Lone Star. And he understood how the land can make a man feel anything is possible. Pete would tell anyone there is no place better than Texas to keep a man moving toward the horizon, not looking back, and always believing there is something better up ahead.

And I’m sure that’s how he’d like to be remembered.