The Rushing Minutes

"No one talks much about their past in Terlingua. The future is not of any interest, either. The present, though, has appeal."

“Well, you know we’re probably too old for this

Maybe the rest of the world is too young

We drive five hundred miles to get loose and get wild

And stay up ‘till the last song is done.”

– Gary P. Nunn, Terlingua Sky

There is a time in Texas when the weight of the sun lifts slightly, and dry, western air eases eastward against the muggy Gulf flow. We call this autumn. Northerners have no ability to notice the subtle change when they visit because the daytime temperature continues to hold around 80 and fair skin still burns when exposed. This is my favorite time of the year, when I travel, almost because of a genetic, migratory instinct, west of the Pecos River.

The desert in the spring and fall is impossible to resist. Along the arroyos leading to the Rio Grande, and west of Del Rio, Mexican sage purples the hillsides and turns the highway into a river of color in October. Southeasterly winds, which often carry particulates from the Gulf oil refineries, have laid down and the air can appear as clean and clear as it was after the earth had first cooled. The great seam where the world and the sky come together keeps easing away from the traveler while maintaining an alluring seductiveness, prompting a failed pursuit.

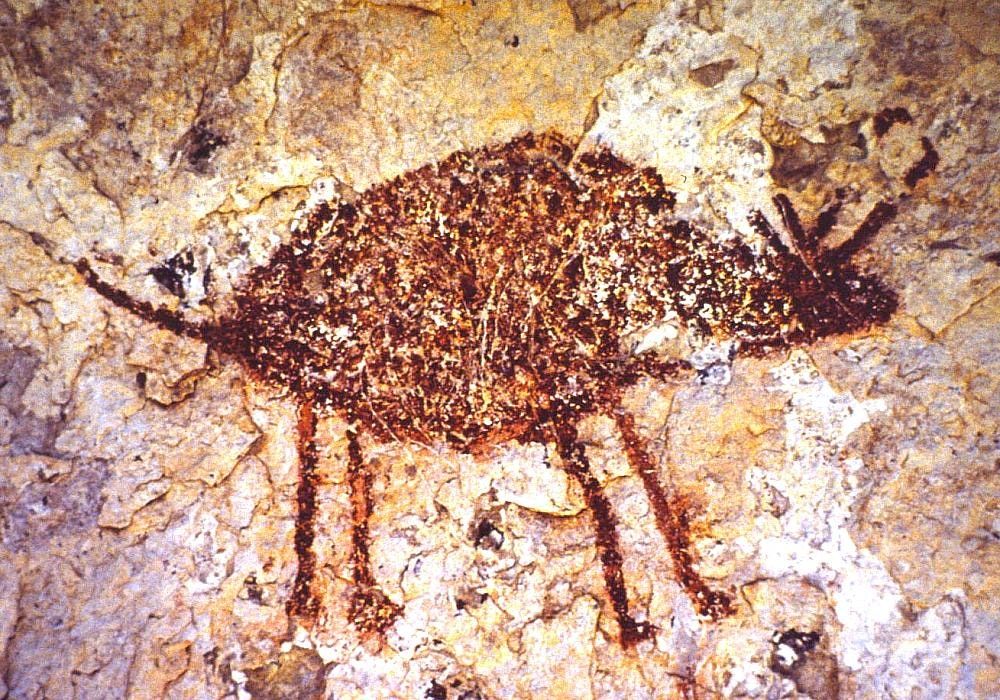

I always stop at the Pecos River High Bridge and look across the far canyon that the stream has cut into the rock. No one moves along this route without thinking about time. It’s written on the canyon walls by the river and the ancient peoples who populated the lower Pecos region and left their art in caves and on stone alcoves. Pictographic paintings and petroglyphs mark the passage of the river as it slips into Lake Amistad reservoir on the Rio Grande and concludes a 925-mile descent from the Sangre de Cristo Range and its headwaters 12,000 feet above sea level in New Mexico. In the 44,000 square mile watershed, wanderers often come across smooth, ancient stones that have been scratched and incised with patterns cut by hands seeking beauty in past millennia.

Humans seem to have a passion to measure their time breathing, a compulsion that in Texas dates at least to the indigenous people living along the Pecos thousands and thousands of years in the past. Like the man on the cliff hundreds of feet above the gently moving water, they must have felt a quickening of their pulse with the passage of years and the seasons racing before their eyes. No prophylaxis exists for that affliction.

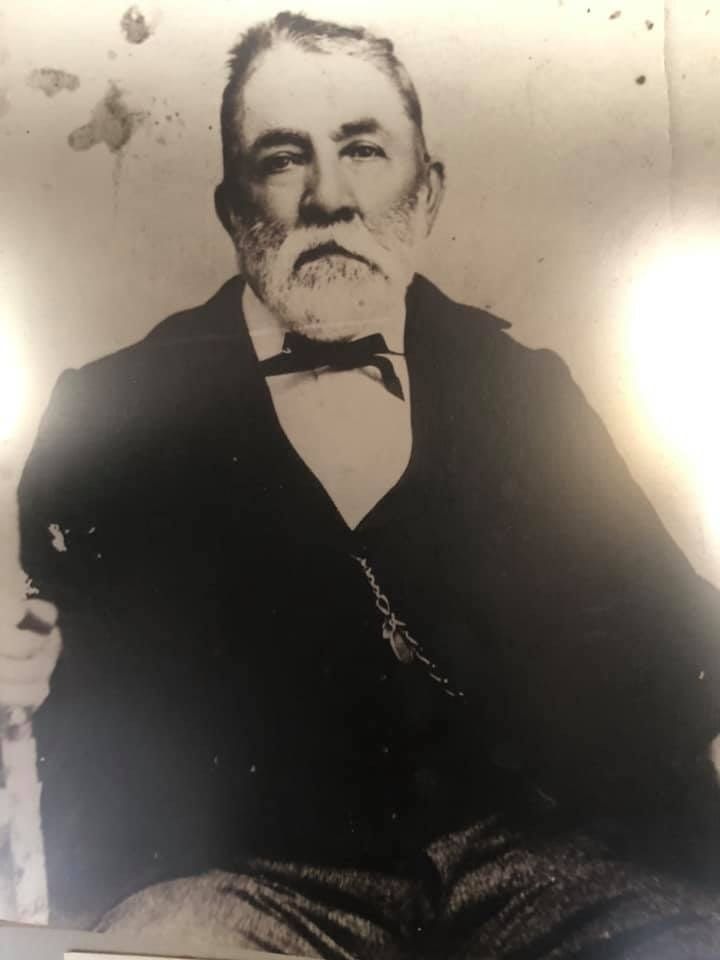

Across the bridge and a few miles up the rugged frontier defined by the river’s watercourse, artifacts still stand of a more recent human encampment. Judge Roy Bean is no less gone than the Jumano and the Comanche and Mescalero Apache people, but his endeavors might feel more relevant, if not current. Bean came this way when he heard railroad developers were laying track across the Chihuahua Desert toward El Paso and the California sun.

Judge Roy Bean, the Law West of the Pecos

Bean settled in a spot called Langtry, which was the surname of the man who managed the Chinese immigrant laborers on the railroad. Oddly, Bean set up saloon in a tent, and later a wooden structure, which were both named the Jersey Lilly. The enterprise was named after his favorite actress in New York City, Lilly Langtry, who was not related to the railroad manager. She was only a face he saw in a newspaper picture and an image that had left him smitten throughout his days. Although he never met the object of his affection, stories often repeated that suggested he greatly desired to be in her presence. Instead, he dispensed justice, or what he decided it was, and became known as “The Law West of the Pecos.”

His combination courthouse and saloon still stand and have become a roadside attraction for travelers wandering far south of the Interstate. I always try to stop unless the sun is lowering fast and there are too many miles to go. Highway 90 becomes a bit of an elk and deer and feral pig petting zoo in the dusk and that is not an endeavor best enjoyed on a motorcycle. I tend to find myself wondering what the irascible Bean might have thought of the concept of tourists, people walking through his old courthouse in their drug store sunglasses and flip flops, or that his legend might have lived on in popular movies, whatever that was.

Time took the judge like it grabbed the Jumano and Comanche and Karankawa, and will snag all of us, sentient or otherwise. On this trip, my goal was to neutralize the clock with a motorcycle. The road running under my wheels has always been fortifying to me, and an open highway suggests a kind of immortality. Really, though, the only way to drag time’s heels in the dirt is to gather with friends and contemporaries. The minutes will still rush past, but they will shine more brightly and burn into memories.

Staring at the highway, I recalled a previous run westward. My friend Greg had invited me to beat back the years and the beers with an autumnal congregation in Terlingua, the mercury-mining ghost town just west of Big Bend National Park, and north of the Rio Grande in West Texas. Retired as a peripatetic photojournalist, he sent out an email to his similarly restless and disturbed cohorts and we made our way to a remote spot in the Chihuahua Desert in view of the Chisos Range. Greg had planned nothing more complex than an eating and drinking assemblage of gray-haired and balding characters that are all trying to age with grace by generally avoiding the burden of maturity.

I invited one of my oldest friends, Ken from Washington, D.C., to join me on the trip to Terlingua. An unfaltering compadre of four decades, he was raised in Texas and had never seen a Comanche Moon over the Trans-Pecos and had not once entered the boundaries of the national park. Ken had also, I decided, become disconcertingly normal and predictable as an adult, and no one would have described him that way as a young man. I might say I made an effective argument that we needed to have a little fun as old pals, but I think he was more convinced by the stents placed around his heart over the previous years.

Ken said he did not expect to see such a treeless terrain as we rolled down the hill into Study Butte. People who love the desert, though, find the topography and vegetation around Terlingua and nearby Study Butte to be uniquely beautiful and riven with light from other worlds and ancient lives. The architecture is mud, rock, and mobile home, but neither fresco nor Athenian marble columns were likely to take a gaze away from the landscape. We followed Greg’s directions and rattled miles down a gravel road.

“You’ll see a Texas flag,” he had written. “And underneath it you’ll see Texans, drinking and eating.”

There were no other houses within sight and the only other indication of humankind’s intervention was the bladed road we had just taken through the desert. On the porch in front of us as we arrived, though, there were ice chests and a table laden with food Greg and others had prepared. A young dog, crazed by the aromas, jumped at the arriving strangers and demanded attention.

“’Bout time you got here,” Greg said. “There’s the food. There’s the beer. There’s the people.”

Almost everyone I met had a camera either in their hand or hanging on a strap around their neck. Greg, now rounded where he used to be angular, had made a long and accomplished career of taking pictures while doing adventurous things like chasing the Shining Path communists through Peru; he appeared to have summoned every one of his photography friends to this stone porch with the low roof beyond the reach of cell signals and rescue vehicles.

Each of these talented people had remarkable stories, though, one of them had been a part of a moment that serves as an icon for our country’s passage through the Vietnam Era. John had taken the famous picture of the Kent State shootings on the morning of May 4, 1970, and his camera captured the nation’s angst with a solitary frame of a grieving student, head tilted skyward in agony, crying out over her fallen friend. He claimed no genius for the moment he had made historical.

“I was a student, too,” John told me. “I was just there and had a camera.”

No one talks much about their past in Terlingua, though. The future is not of any interest, either. The present, though, has appeal. I heard a story of a newcomer that was asking questions to a stranger about a local resident and was getting not much more than grunts for answers. His persistence ended with the interviewee telling the interviewer, bluntly, “Look, there’s a phone book over there. I know his number is in it. Go call him and ask him yourself.” No ethic prevails in Terlingua more than privacy. The romantic notion is that half the town is populated by people on the run from creditors, spouses, and the law, but my sense is they are just trying to escape the grind and the expectations of American life. Terlingua offers simplicity.

I have never been, however, able to overcome my curiosity. Our host, Carl, struck me as an intriguing individual. His hair and beard hung long and white beneath his cowboy hat, and he had set his house so far into the desert that the nearest neighbor was not visible. In his early 70s, Carl and his dog sought the quiet but how was I supposed to not be interested in what delivered him to this place?

“What did you do before you got here, Carl?” I asked.

“Military. Air Force. 37 years.”

“Oh yeah? What did you do?”

“Intelligence.”

Generally, when this word is spoken by a retired service member it tends to be understood that no further details will be solicited. Consequently, we moved on to talking about his new dog.

Presently, lines of light set out by the sinking sun began hitting the Chisos Mountains to the southeast of our porch. In less than a quarter hour, the range faded from red to orange and then darkened to purple with flecks of yellow. The talkative Blair had been profoundly silenced by what he was observing. He, too, had been an expert photographer for a major Texas newspaper and had run to a desert adobe to enjoy his winding down. At the precise moment of perfect illumination by a declining sun on the Chisos range, Blair got everyone’s attention when he pointed at the mountains.

“Not too shabby a light, that, eh?” he said.

Artists and photographers spend their lives searching for the kind of color and definition that spills hourly across the desert in Terlingua and the broader Trans Pecos region. When they finally discover it, they find it impossible to record in its variegations on the rock, nor can they forget, and they want to stay in constant repose and wait for the next circling of the sun.

The following day I drove my D.C. buddy Ken along the river road and took him on a short walk to show him The Window in Big Bend National Park and we ended up on the porch of the Terlingua General Store. We sipped Mexican beers, listened to the out-of-towners and the locals talking, and stared off across the desert to where the walls of Santa Elena Canyon rose over the big river.

Staying a beer too long on the porch of the general store, we later found ourselves climbing a different gravel road to Cynthia’s house for more food and drink. She was another one of Greg’s friends who had agreed to host his collection of eccentric associates. A bonfire flew at the night in a courtyard below her porch and we ate vegetarian food and bread cooked in a solar oven. Guitar music came out of the surrounding darkness. Cynthia, slender and charming, had been a river guide and had taken countless tourists down the Rio Grande. She was marked by the sun.

Although I did not meet him at the time, I later learned that Ara had come in out of the desert. A master chef and brilliant photographer, Ara was, at that time, wandering the American Southwest on a motorcycle with a sidecar for his dog “Spirit.” Ara still writes the mystical and dreamy prose of a child of the sixties and posts stunning photographs of the desert as he searches for peace after losing his son. The colors of the world he sees give him hope, but his words suggest the hues that fill his eyes are fading with time.

Ken and I eventually left, reluctantly and late, bound for Austin. I am never confident I can depart Terlingua and the Big Bend and think that someday a kind of paralysis will conquer me, and I will not be able to turn the key to start my truck or my motorcycle. As we left the national park and drove toward the Permian Basin, Ken began to feel dizziness and we found ourselves searching for a doctor or a hospital. Altitude sickness and the lingering effects of beer were potential causes, but Ken worried about the accumulated years of indiscrete behavior and those stents in his heart required caution. I had had no better friend, and as we raced across the Edwards Plateau with him holding his chest, I insisted he not die in my truck and leave his memory in the passenger seat.

I am pleased to say he did not. We found a Sunday country doctor, a physician associated with a heart hospital in Austin, and he conducted blood tests. A recommendation was made that we await an ambulance or a helicopter to convey Ken to a major facility in San Angelo. He demurred and ignored the expertise. A nurse rolled him in a chair back out to my truck, asking, almost judgmentally, “Are you sure?” Apparently, he was. Ken’s spinning head stabilized, and we turned east toward the city, moving him closer to his home.

And all our minutes are still rushing past.

James Moore is a New York Times bestselling author and Emmy winning former television news correspondent. He has contributed on-air political and media analyses for major news networks and his written opinions have appeared in publications around the world. He is at work on his seventh book.