The Tragedy of Sky Queen

28-year-old Karen Key was shining up a star for herself in the competitive business of TV news. Key was the first female helicopter news pilot in TV journalism. She could fly a Bell Jet Ranger and talk into the camera with the Rockies as a backdrop - her career was ascending as fast as her takeoffs.

“Television is called a medium because it is neither rare nor well done.” - Ernie Kovacs

In the newsroom, they called her “Sky Queen.” The nickname was clearly a riff on the black and white TV series from the fifties, which was about a rancher who used his Cessna to rescue hikers and help capture bad guys. The aircraft was named “Songbird” and his niece Penny was often a part of the successful outcomes of Sky’s adventures.

“Sky Queen,” though, was not old enough to have even heard of the TV show that gave her the moniker she took around the city of Denver and the Rocky Mountains. Twenty-eight-year-old Karen Key, though, was shining up a star for herself in the competitive business of television news. Blonde and telegenic, Key was the first female helicopter news pilot in the history of TV journalism. The fact that she could pull pitch on the collective, fly a Bell Jet Ranger, and talk into the camera with the Rockies as a backdrop, meant her career was ascending as fast as her takeoffs when racing to cover breaking news.

Which, it turned out, was too quick.

The era of helicopter news reporting is considered to have begun in 1971 with pilot Jerry Foster, in Phoenix, Arizona, and KOOL-TV executive, Homer Lane. Foster, a local search and rescue pilot, was offered a job by Lane to fly a small chopper and get the station’s reporters to the scene of stories faster than driving, and do traffic reports. Foster’s aviation skills, which included taking great risks, and his personality, provided KOOL-TV with big wins in a competitive broadcast market. The idea of using helicopters to cover the news spread quickly to major metros, and, eventually, stations across the land were trying to outrace the competition to be the first to big stories, which was followed by promotional bragging on the air.

The One Camera Black and White TV Series

When I was offered a job by the ABC-TV affiliate in Denver, I was met at Stapleton International Airport by the news executive, who had arrived on the station’s helicopter. My assignment was to cover Colorado, and points beyond, west of the Continental Divide. My new employer had decided my engagement was to begin with a flight over the Rockies into Glenwoood Springs to meet my partner and photographer over dinner, and check out the news bureau inside the historic Hotel Colorado. After we crossed the divide, the pilot chased a herd of elk and then ducked us under a rainbow that was flashed across the sky by a passing thunderstorm. I had already hitchhiked and motorcycled Colorado’s back roads several times and thought that I was about to begin the best job in American TV news.

Only a few weeks had passed when the Sky 9 chopper had crossed over the mountains to pick us up and begin a search for a downed aircraft. We flew grids for three days until spotting a debris field. The mountains had shredded a twin-engine plane into what looked like beer cans scattered across a snowfield in the sun. Nine souls had been onboard. There were numerous other flights we made looking for the lost and missing and every time I went up there were reminders about the dangers of flying in the Rocky Mountains. In the summer, rain storms materialized in minutes like monsoons in the tropics, and even on clear days the winds down the canyons and up the ridge lines and across the ragged peaks were dangerously twisting, diving and rising with a power to transform light aircraft into scraps of aluminum.

I had no fondness for traveling anywhere via helicopter. In Omaha, the station where I was employed prior to Denver, used a Hughes 269C chopper, which was little more than a bench seat in a plastic bubble attached to a four-cylinder engine. On hot days, getting airborne with two passengers and TV gear tended toward the excessively adventurous. I often felt like we were vibrating to the point that bolts were going to come undone. The chopper was known less than affectionately in the newsroom as “Roto-Death.” My decision about accepting employment with the Denver station might have been different, too, had I been aware the year prior to my arrival their helicopter had flipped and landed upside down while flying a search near Fort Collins. The pilot and photographer were not injured, but the incident was suggestive of potential tragedies in the coming years.

The Denver TV news market in the early 80s was extremely competitive and the three network stations were joined in helicopter battles to attract viewers. The aircraft were painted with bright logos and became flying billboards promoting the newscasts as they moved across the dramatic backdrop of the Front Range. Because managing aircraft over and between mountains is dangerous, pilots hired by TV news executives had experience ranging from Huey gunships in Vietnam to flying bush in the jungles of New Guinea or lifting logs above forests in the Pacific Northwest. Aviation safety was always the primary consideration when flying journalists to assignments, and the pilots all displayed great skills. There was, therefore, no simple method for distinguishing excellence or luring more viewers.

Unless you could find a star.

She was down in Phoenix, competing against Jerry Foster, the pilot who has started the trend of TV choppers covering the news. Karen Key was 28 and had acquired her license with the requisite 200 hours of flight time. Immediately, she attracted attention, on and off the air. In the rank sexism of those years, one writer described her by saying she could have been “Madonna’s stunt double, and like Madonna could rock a skintight jumpsuit.” Looks are attributes that help on television, not flying complicated aircraft, and Key, with her limited experience, had trouble keeping up with Foster. The cops and emergency techs all knew Foster and he was usually tipped on stories before Key got word. She tried charm to reduce the competition and wrote Foster a letter telling him there was no reason for him to feel “threatened by the little blonde with the cute behind.”

The executive who had hired me in Denver, meanwhile, had been lured away to the station across town and was looking to make a quick impact for his new employer. A tape of Karen Key had shown up on his desk, and after a visit for an interview, she was offered the job of pilot and reporter for KOA-TV. Key had told her new boss that she had 1800 hours in her flight log books but there was never any indication the station had sought confirmation of her records. In fact, a few calls to Phoenix would have provided information that police were certain she had arrived at one story with alcohol on her breath and that they did not trust her piloting skills. Knowledge of her reputation might not have made a difference in the environment of the TV news business in the early 80s, but some consideration ought to have been given to the fact she was operating her aircraft mostly in sunny skies over open deserts, which is considerably different than finding your way through the constantly changing weather of a massive mountain range. Regardless, Key expressed great confidence in her abilities in her conversations with management, and the Denver station was apparently reassured to hear she had also flown early in her career for Bell Helicopter in Fort Worth.

Key had to have felt the competitive pressures in Denver the day she took her first flight. There were times when the other two pilots were able to make it over Loveland Pass to reach a news story and she would set her ship down before Eisenhower Tunnel on Interstate 70. Hardly a year after she had arrived in Colorado, Key’s pager beeped with news of an airplane crash. A Pioneer Airlines turboprop had gone down between Colorado Springs and Pueblo. She raced to JEFFCO airport, hoping to be the first into the air to search for the missing aircraft. The weather, however, had turned bad with freezing rain and fog mixed with snow. Pilots for the other two stations, who also kept their helicopters at the same location, were not going to fly. The ceiling was too low, and weather too risky. Key was urged not to go up, but ignored the pleadings.

Larry Zane, who was also 28, a flight mechanic and friend of Key’s, had agreed to go with her on the search mission. JEFFCO tower gave her a clearance and the KOA helicopter rose to just below the cloud ceiling and began to follow I-25 southbound in the direction of the anticipated location of the wrecked Swearingen SA-227AC passenger plane. Key had to be hopeful she was about to win praise for getting to the wreckage when the more experienced pilots refused to risk a search mission. Motorists along the Interstate described seeing the helicopter flying low and slow with landing and searchlights sweeping the roadway in the snow. Several indicated they had been able to keep pace with the aircraft until the highway bent away from the mountains and Key turned toward the west.

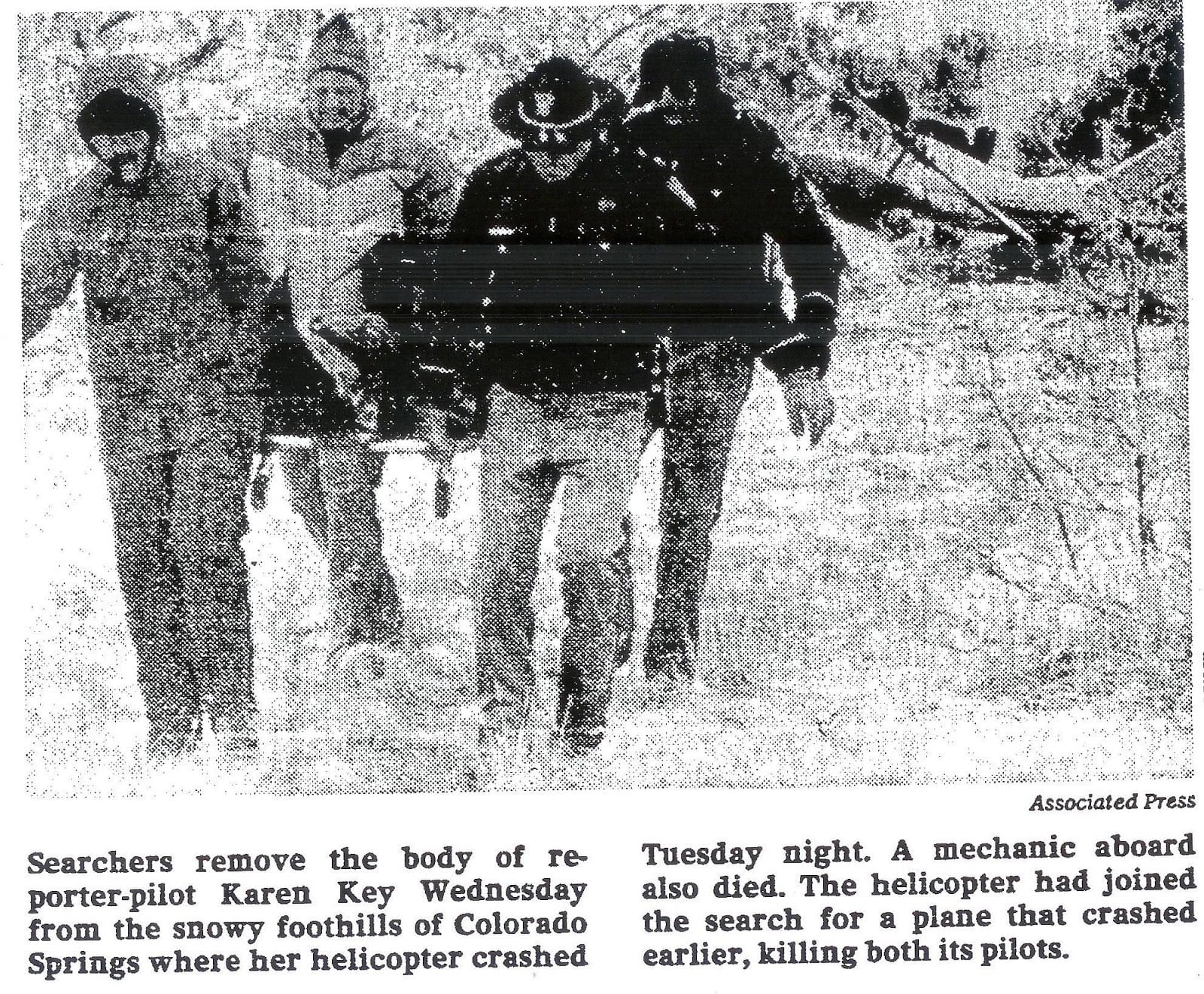

The KOA helicopter was not discovered until the next morning. Key and Zane had died when the aircraft hit the tops of pine trees on a knoll near Larkspur, Colorado, and then fell on its side. She was apparently impaled by the control stick. A toxicology test indicated a blood alcohol content of .093 percent, which was just below the legal limit at that time. An FAA investigation cited numerous other factors in the cause of accident report in addition to “pilot impairment.” Those reasons for failure included Key’s overconfidence in her personal ability, a lack of total instrument time, inadequate preflight preparation, self-induced pressure, snow, ice, and fog. Investigators might have added that she was working in an industry that placed less value on her life than it did on an additional rating point to show advertisers.

TV Stories Regarding the Key/Zane Crash Tragedy

Karen Key and Larry Zane died in their youth for a news story that might have run 90 seconds to two minutes on a newscast. The station manager, Roger Ogden, who had hired Key, told the Denver Post in a copyrighted story that he had been told by Key that she had more than 1800 hours of flying time in helicopters. Did he ever see her flight logs? According to the newspaper, her claims were considered “highly unlikely” by other news copter pilots and her assertion that she had flown for Bell Helicopter was flatly false. Federal Aviation Administration records accessed by the paper’s reporters indicated that Key had 200 hours air time when she was granted a commercial pilot’s license but would have had to get more than 100 hours every month she worked in Phoenix to accumulate the 1800 she claimed when she was hired by KOA-TV in 1981. The day after the crash the station acknowledged on the air that it had still not seen her pilot’s logs. Bell Helicopter in Fort Worth said she had simply been an administrative assistant and never flew for the manufacturer.

The station’s editorial staff lionized Key as a hero who was always trying to help people in trouble, which was, in some respects, demonstrably true. Anchors, though, went on the air and blamed the criticisms of her skills on “male chauvinism” and interviewed her FAA examiner who claimed her skills were “well above minimums,” which is hardly a description that offers confidence to passengers rising up above the Rockies sitting next to a pilot with Key’s experience. Astonishingly, one editorial by an anchor concluded by saying Key was “not the first, nor will she be the last journalist to die doing their jobs.” The narrative suggested that she was a casualty in a “great tradition that had kept Americans some of the most informed people in the world.” Her death was obviously nothing like the story the station’s writers were selling. Key was a victim of her own ambition, bad judgment, and a toxic competitive environment that took risks with employees’ lives to make more advertising dollars.

Nothing changed after the crash that killed Key and Zane. Between 1980 and 1994, my former station lost six helicopters and five employees. Almost thirty years passed from that treacherous December night in 1982 when Key’s ship went down, before Denver news executives realized the absurd cost and risk of rushing to news in helicopters. An agreement was forged in 2011 for the three legacy network stations to share the lease of a single helicopter and to have equal access to all video acquired through its dispatches. There seems not much doubt the helicopter facilitated and even expedited the coverage of news in major metro areas like Denver, Houston, and Dallas, where traffic is an impediment and the cities sprawl across broad landscapes. The question no one bothers to answer in the industry is whether it is truly important to be first by a few minutes.

And is winning the race worth the risk?