The Wounds of War

I read the history of his division. I wanted to know what he saw and did - it might explain his emotional instability and brutality to his family. I refused to relent as the Mississippi night lowered and the crickets made their fractured music in the darkness.

(Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted me to think of all the harm done by war during my lifetime and the people I know who were permanently wounded. I don’t think anyone ever comes back from the violence without injuries, physical or mental. My father served in the European Theater of World War II as a sharpshooter and refused to speak of it until very late in his life. I think what he carried within him explained much about the hurt he put back into his little world).

“It is forbidden to kill; therefore all murderers are punished, unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.”

- Voltaire

After my father completed his decades of labor for the automotive plant in Michigan, he felt a need to go home to Mississippi. A few of his siblings were still living and he wanted to spend more time with them and to be around the woods and fields he had known as a young man. People tend to wish for a return home late in life, maybe to confront the past or build different, more comfortably abiding memories to enjoy in their final years. My father was not unique for this sentiment. The move also situated him closer to where I lived in Texas and I found occasions to ride my motorcycle the hundreds of miles between us to talk to him and try to find an understanding and a peace with a man, who, to me, was mostly unknown.

There was much I wanted to know, and questions that were certain to be uncomfortable for him, but I started with the war. These early conversations were always on the porch of a house he had purchased in a small town not too far off the Natchez Trace and north of the Choctaw Reservation where he had spent much of his boyhood. I did not sleep in Daddy’s house because of the filth and clutter. He lived almost like a forest creature and never picked up or put away things; a bottle of Ivory Soap was on the fireplace mantle, engine oil containers sat on the edge of the kitchen table, a screwdriver in the sink, dinner plates never washed were in every room, newspapers on the floor, dust and mold spreading across most surfaces, virulent and thick in some spots. I brought my camping tent on the trip, tied to the back of my motorcycle, and slept in his yard near the garden. I told him I liked to be outdoors and that his house was too dirty for me to be comfortable. He ground his teeth but said nothing. Accepting he was no longer in charge was always a struggle for him.

Daddy was not a drinker; even in his most extreme, uncontrolled rages he had been as sober as he was dangerous. I never saw him have a beer when I was a boy, nor was there any type of hard liquor visible in the house. He may have had a nip with his hunting buddies, but we never saw evidence of any drunkenness. In retirement, though, he had been told about a remedy that might help his rheumatoid arthritis, which plagued his back after a life of lifting and carrying and pulling. A friend had informed him that a little glass of whiskey, neat, with a peppermint candy in the bottom of the drink would ease the pain and ache in his bones. I had hoped it would also loosen him up to tell me stories that had gone untold.

I mentioned I had a fifth of Jack Daniels on my motorcycle in a pack, and some peppermint, if he wanted to sip while he sat the porch swing and waited on the sunset. Daddy got up without speaking and went inside and came back with two of the cleanest glasses he could find, and I got the whiskey off the motorcycle. When I walked back up the steps, he stuck out his glass and I dropped in a peppermint and then poured four fingers over the white and red striped candy. I was determined to hear about a part of his life he had not ever shared. Ma had said that he would not talk about the war to her in the two plus decades they were married. She thought there might not be anything to tell, but that seemed unlikely to me because he had served in France with the 3rd Infantry Division.

All conversations, though, had to begin with Alaska. We spoke of Alaska every time I was with my father, and his descriptions of the state were as detailed and wondrous as a guide who had spent all his days wandering the Wrangell Mountains or hiking Denali. Daddy had never been there, though; he had only seen pictures in magazines, and he thought Alaska was where worthy people lived in a proper fashion with nature and self-reliance. One of the primary goals of his existence was to see Alaska; he planned to take a ship up the Inside Passage. I let him ramble about the wild game and the fish and rivers while the whiskey did its work and I told him I would like to go along when he finally made that trip, though I knew I’d not be invited.

“Well, you ought to, buddy boy,” he said. “You think you seen a lot in your TV doin’s but you ain’t seen much till you seen Alaska.”

“Might be true. Looks like the geography is as beautiful as anywhere in the world, at least in pictures.”

He tipped his glass and fingered the sticky candy in the bottom.

“You reckon this helps?”

“Can’t hurt, Daddy. A little lubrication is good for our veins and bones, don’t ya think?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it’s just the whiskey makin’ me numb.”

“Don’t matter, at this point in your life, does it? If it helps you not to hurt and suffer, can’t be all bad.”

“Well, it ain’t no cure and I never said it was.”

“I didn’t claim you did. I just thought it might be nice to have a drink with my father.”

“Okay then.”

A pickup passed on the state road about a quarter-mile distant and we heard the loud, broken tailpipe blaring exhaust noise down the concrete. The sun was below the horizon, and we had not turned on lights, which made me think he might be comfortable because I could not see his face, especially if I could get him talking about France and World War II.

“You know I’m a reporter, so I like to ask questions and learn things, right?”

“You gonna ask me somethin’?”

“I was just wondering about when you were in France.”

“What ya wonderin’?”

“Where were you?”

“That Alsace Lorraine part, I think they called it. I don’t remember, exactly.”

“What was that like?”

“Was like war, that’s what it was like. What you think it would be like?”

“I don’t know, Daddy. You never talked about any of it. Ma said you never even told her anything.”

“Well, it ain’t a damned thing ya talk about. It just was, and I got through it. That’s all there is to it.”

“You can’t tell me anything about it? What you did? What did you have to do?”

“I did what everybody else did, damnit.”

“Which is what? Don’t you think after all this time it might be good to just talk about it to someone who cares?”

“Naw. Hell, naw. Talkin’ about it don’t change a damned thing or make anything better.”

“I don’t understand,” I said.

“Well, there ain’t nothin’ to understand, buddy boy. That’s all.”

“Okay. I guess.”

A Portrait of the Warrior as a Young Man

I extended my arm and held the bottle of Jack into the light from the living room window. Daddy put out his glass and I poured, and then handed him a peppermint, which he unwrapped and dropped into the glass before he sipped. I waited for him to speak again but he was silent, and we both watched as lightning bugs rose up out of the Mississippi long grass growing around his house.

What I knew was that Daddy had been a Private First Class and sharpshooter in the Anti-Tank company of the 3rd Infantry, which was part of the Sixth Army Group with orders to drive the Nazis out of the Alsace Lorraine region of Northeastern France. He was serving in a battalion fighting in that section of the European Theater during the last two years of the war. The U.S. had liberated the Nazi-held positions to the north and south as well as Lorraine to the east but were unable to clear the central part of Alsace, which became known as the Colmar Pocket, named after a small town at its geographic center. The battle intensified when the German Nineteenth Army launched operation Nordwind, attempting to push back the Americans and the French and hold the pocket.

The fiercest part of the combat was from January 22 to February 6 of 1945 during what the Army’s official history described as “incessant fighting” conducted through “enemy-infested marshes and woods, in heavy snowstorms, and over a flat terrain crisscrossed by a number of small canals, irrigation ditches, and unfordable streams, terrain ideally suited for defense.” The topography was made even more challenging for advancing Americans by the weather, which was detailed by a French General as “uncommonly cold” for the region. The term “Siberian” was used for comparison. Three feet of snow fell during the engagement, temperatures dropped to -4 Fahrenheit, and strong winds scoured the battleground and piled up problematic drifts.

The initial objective of the assault was to reach the 111 River and lay down a bridge to enable armored units to cross and support the 30th Infantry. The portable bridge collapsed as a German Panzer brigade attacked, though, and the 3rd Infantry elements were forced back into fighting house to house and street by street, decidedly outnumbered and outgunned. The snow was knee deep and thick with mines as waves of German armor and infantry kept coming at the Americans, but they ultimately managed to hold the bridgehead. In a week of fighting and dying and living in the cold, the 3rd crossed the Colmar Canal in rubber boats and moved to capture six towns from the enemy in just eight hours. After enduring 500 casualties, the German garrison was cut off at Colmar, which assured the fall of the city.

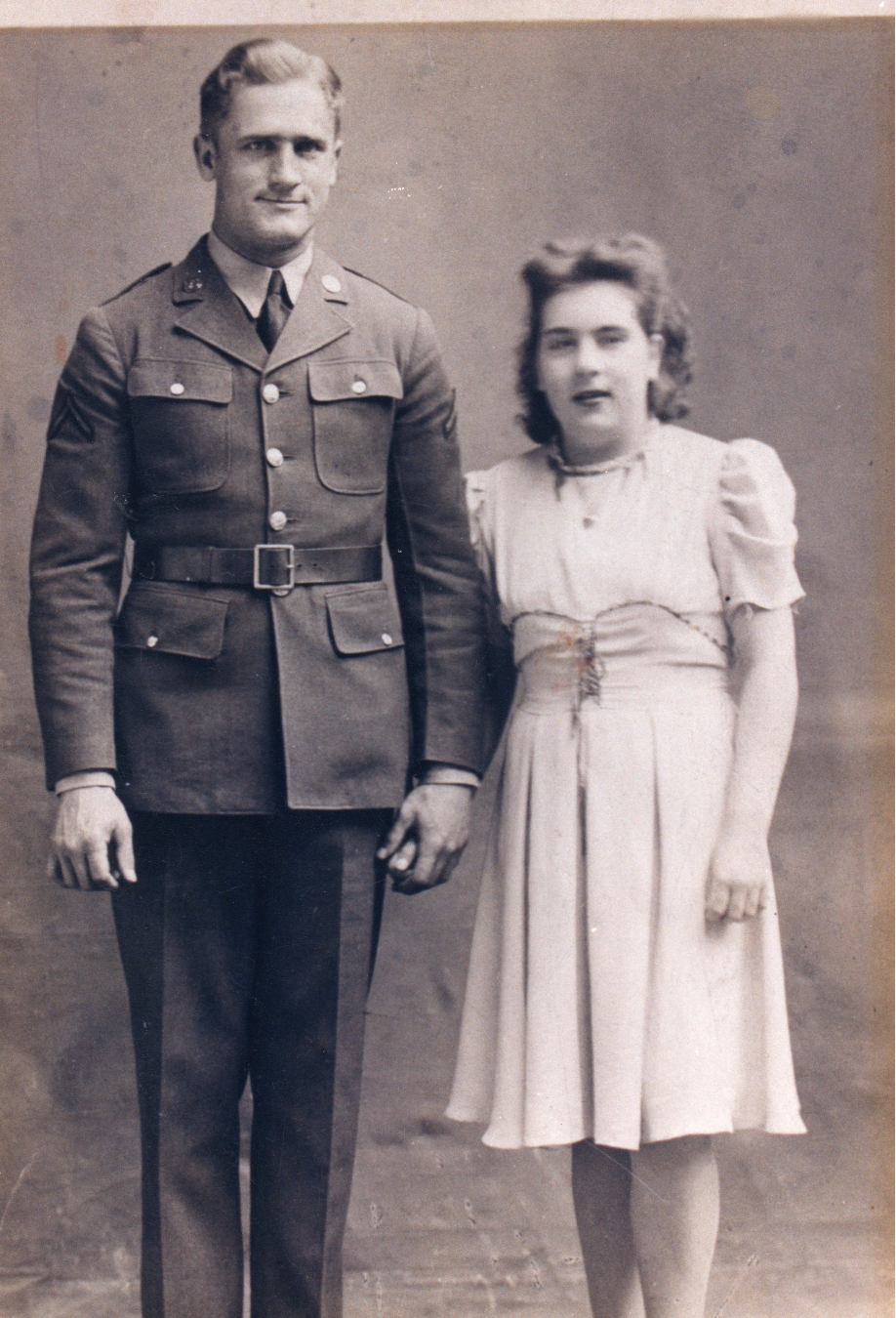

My Parents, James and Joyce, in Love and War, St. John’s, Newfoundland

The 3rd then moved south toward the Rhine and the Rhine Canal and took two strategic bridges to complete what was frequently called “one of the hardest fought and bloodiest battles of the war,” probably because Hitler viewed that region of France as historically sovereign territory of Germany; a loss would also signify the end of German occupation of the country. By the time the Alsatian Plain had been completely secured, the 3rd Infantry Division was credited with annihilating three enemy divisions, including the feared 2d Mountain Divisions and the 708th Volksgrenadiers Division, badly mauling the 186th and 16th Volksgrenadiers Divisions, capturing 4,000 prisoners, ending German occupation of twenty-two towns, and inflicting more than 7000 casualties on the enemy. The final report stated that the 3rd also killed a disproportionate number of the enemy compared to the total it took as prisoners of war.

Daddy had given me a copy of his discharge papers many years earlier and I had read some history of his division. I wanted to know at least a part of what he saw and what he did because I felt that it might help explain his emotional instability and his brutality to his family, and I refused to relent as the Mississippi night lowered and the crickets made their fractured music in the darkness.

Before the Sound of Shots Fired in Anger

“Weren’t you part of that last assault in Northeastern France, Daddy? Were you there?”

“I was where we went. I don’t even know exactly. I told you it was the Alsace place.”

“What did you have to do?”

“Hell, you know what I had to do.” He sipped the last of his second glass of whiskey and got up from his chair. “I’m goin’ to bed, buddy boy.”

“I want to talk about this some more, Daddy.”

“I know ya do. But I don’t. And I ain’t a gonna.”

His balance was affected by the alcohol, and he leaned on the frame before he pulled the screen door open and let it slam behind him. I watched him switch off the living room lights and go down the hallway littered with clothes and shoes he had not bothered to pick up and put in drawers or closets. His broad square shoulders were going rounded and seemed to curl forward and he struggled to maintain his proud, erect posture. I fell asleep on the porch listening to the country night and thinking that the world had mostly taken from my father and had given very little in return.

The next morning, we drove up to Starkville to get the oil changed in his car. We also stopped at McDonald’s because he was fond of their specials for seniors. My father was always conscious of money, which was understandable, but also sometimes nearly debilitating, and even embarrassing. Daddy was known to pay attention to sales at Goodwill, but often took his frugality to the point of absurdity. They ran grab bag specials by filling brown grocery sacks with unnamed clothing items and selling for $1.50 each. The bags were stapled shut to avoid shoppers picking through the contents before purchasing. Blind buying of the surprises inside was supposed to be part of the appeal. Daddy sometimes found a shirt or a pair of pants that fit him after he took his bags home, but he was never prouder than when he showed up in a worn and faded blue seersucker suit that had come from a brown Goodwill bag and was always fond of asking people to guess how much he “had to give” for it.

McDonald’s attracted older diners in the mornings, and they sat and drank coffee and ate Egg McMuffins and talked across the tables. Daddy liked to chat with the strangers, probably because he lived alone, and his voice could carry across any room. Instead, on this morning, after he had finished slowly eating, he was quiet and stared at his coffee. I waited patiently for him to reveal what he was thinking, knowing that he might not say a word until prompted.

“You asked me to tell you somethin’ about the war,” he said.

“I’ve asked you many times, Daddy. You know that.”

“Well, I’m gonna tell you somethin’, but I don’t wanna talk about it after I’m done and I don’t wanna answer any questions about it, neither.”

The narrative he shared was about an incident that occurred after the 3rd Infantry had ceased combat operations in Northeast France. German POWs were being put on trains to be shipped to repatriation camps and his unit had been ordered to guard the trains and not let anyone escape. Prisoners were loaded onto freight cars, sometimes the same ones that had carried Jews to concentration camps, and the POWs were told getting off was strictly prohibited under penalty of death. Daddy said he did not know if there was a portable latrine or a slop jar that the Germans could use on the train or if they were simply expected to defecate in the same space in which they would travel.

“I was just standing there along the tracks with my gun over my shoulder and talkin’ to my sergeant when he told me to turn around and look up the tracks,” Daddy said. “Some damned Kraut had jumped down from one of the cars and had walked off to take a piss. That’s all, just take a piss.”

His sergeant immediately reminded him of his orders. Daddy remembered the brief conversation in detail. “He said, ‘Take him down, private. We have our orders.’ I told him I couldn’t shoot a man for just takin’ a piss. He said orders was orders and I knew what I had to do. I looked at him like he was crazy, but I raised my rifle and stared at the German a long time through my scope. He was just some blonde-haired damn teenager, didn’t look old enough to be outta school, much less fightin’ in a war. I didn’t see no reason to shoot nobody. The war over, far as we was concerned.”

In this moment, though, it was not, and his sergeant became threatening.

“Private, I am ordering you again to take down the enemy prisoner. Your failure to comply with this order puts you at risk of court martial at the end of the war. Failure to follow yours orders at this point would be very foolish.”

Daddy remembered that last command, but nothing stayed in his memory with the same intensity as when he recalled what he did to POW.

“I lifted my rifle, he was pretty far off, and I thought I could miss him, and he’d be warned and run back into the freight car. But the sergeant said I had been assigned to guard duty because I was a sharpshooter, and he didn’t expect me to miss. I didn’t, neither. I decided I wanted it to be quick for him and me and I put a bullet through his head. When we went up to him to check he was dead, we saw he weren’t nothin’ more than a boy, just like I thought. His cheeks was even pink, and I remember his eyes, like he was shocked. He lay there all dead and gone; still had his pecker in his hand.”

“Jesus, Daddy. I don’t even know what to say.”

He sipped his coffee. “There ain’t never anything to say about any of all that, like I told ya before. But I been seein’ that boy just about every day of my life ever since. I think about what his life mighta been like, even, that sorta thing. Just didn’t seem right I had to do that. Still don’t seem right.”

“It wasn’t. But you aren’t guilty of anything.”

“I pulled the damn trigger, didn’t I?”

“But it was war, and you were following orders.”

“None of that meant a damned thing when I saw that boy’s face. Still don’t.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Me, too. Have been my whole life, and it’s why I never talked about it. I try not to think about but still do here some forty years on.”

No response from me was adequate, so I said nothing. Riding the motorcycle down the two-lane blacktop through the loblollies and cypress the next morning and heading toward home, I was unable to stop thinking about Daddy’s description of the German boy and what war must have done to his family and how it had harmed my father. Understanding his anger at the world as he tried to live his life became a bit more possible for me. His wound seemed more harmful than an injury from an enemy’s bullet or shrapnel. Maybe I could forgive him for how he had treated his family; I just didn’t know.

But I felt like he had at least given me a reason to try.