What Kind of an American Are You?

"Trump’s anger is not likely to be constrained by a courtroom. He will send emails to supporters, many of whom struggle to pay their own bills, begging to give him money because he’s a victim. They will send their cash and credit card payments to a man who claims to be among the world’s richest."

The first criminal trial of an American president is likely to bring more division, and even suffering, to the country he proposes to once more lead. The salaciousness of the story that has brought him before the bar of justice will further demean the highest office in the land, which tends to bear the imprimatur, “Leader of the free world.” The nation’s entire population, already agape over the reportage, will hear details of sex with an adult film actress while the future first lady was home with a new baby, and how money was paid to keep the porn star quiet about a tryst with the man who would be president.

I wonder if a $130,000 payoff to cover up extramarital sex can make our political divisions even more acutely dangerous. The accused’s anger is not likely to be constrained by a courtroom and he will send out emails to supporters, many who are struggling to pay their own bills, to give him money because none of this is fair and he’s a victim, and they will send their cash and credit and debit card payments to a man who claims to be among the world’s richest. Even our horror and embarrassment will become transactional, which is unsurprising for a president who has specialized in bankruptcies and failed businesses. Pollsters say a felony conviction for cooking his books to hide the bribe will cost him support, even among his red-hatted minions.

The former president laces his reelection rhetoric with terms like “bloodbath” and phrases suggesting “all hell will break loose,” determined to suggest that a dystopia awaits Americans if they do not end his prosecutions and restore him to the White House. Little imagination is required to envision a scenario where the republic comes undone, at least partially, after a conviction of the serial adulterer and the reelection of the incumbent. Anger on the right might manifest in violence, though the notion of a civil war seems improbable. Putting on camouflage clothes, grabbing a gun, and shooting fellow citizens randomly only makes you a criminal, not a patriot. Our differences cannot be resolved by an internal American conflict involving combat, but they are too stark to be simply swept from the room by an electoral vote.

I do not understand how any citizen can support a man who ridicules the handicapped, calls members of the military “suckers and losers,” fails to pay the vendors who work on his projects, demeans women with blunt sexual allusions and brags about taking away their right to control their bodies, continues to claim he won an election that more than 60 courts said he lost, and lied, according to the Washington Post, more than 30,000 times during his four years in office. What does it take to disqualify him from the job in the minds of MAGA men and women? Is it okay for a president to pathologically lie and believe in a reality that exists only in his troubled mind? There is no remaining rational right wing when every Republican officeholder hurries to Florida to politically genuflect before a man who sprays his face orange and brown when he arises in the morning.

The verdict in the New York trial, and the outcome of November’s election, will not end the great American political rift. In fact, it will likely deepen. New theories of stolen votes will circulate, regardless of the lack of proof, and MAGA warriors will add fanciful implications to the hackneyed mantra of, “Take our country back.” Who took it from us? Perhaps, we gave it away to a conman. The former president’s campaign operatives are already scheming methodologies for challenging the vote while there are, undoubtedly, Q-Anon clowns and angry incels just waiting to take to the streets with their patriotic delusions. We might all be Americans, but we are of different types, and the middle ground has been washed away by a sea of vitriol.

The idea of a new Civil War seems preposterous to me. A more likely scenario that occurs over the course of decades is a kind of “Balkanization” of this country, a breakup into regions that are each independently governed and influenced by relationships with foreign powers. Imagine the traditionally liberal Northeast aligned, economically and politically with Europe, the West with Asia-Pacific influences, Mexico and cartels might gain some control in the Southwest, and Central and South America pull strings in Dixie and the Southeast. That’s a movie I’d like to see, and not completely improbable if we cannot reconcile deep differences in our politics and public discourse.

Alex Garland’s new movie, Civil War, suggests a modern version of the War Between the States is not impossible. The trailers make the film appear more like a war movie than an examination of how failed political debates can lead to catastrophe. Audiences are more compelled by bang, bang and explosions than watching politicos argue until guns are pulled, I suppose. There is one scene in the trailer, however, which implies a contemporary cause for the fictional conflict. Austin actor Jesse Plemons, one of the combatants, confronts a small family on the run from the violence, and decides he needs to know their allegiances. When he is told, “But we’re Americans,” Plemons is not satisfied.

“Yeah,” he says. “But what kind of Americans are you?”

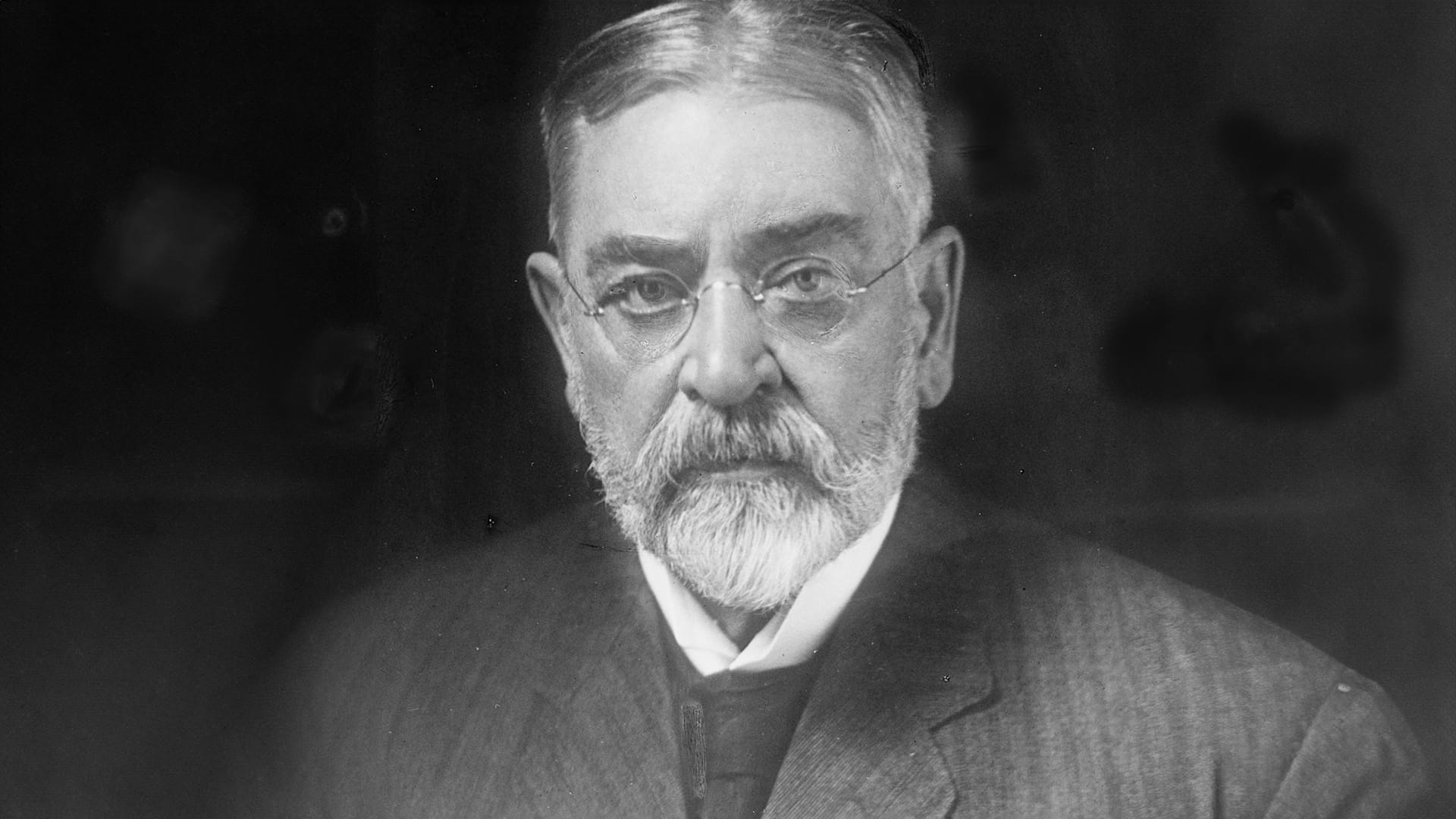

The idea that there is more than one kind of American is as disturbing as it is factual, and violence and brutality related to our politics has been inescapable. Some of this can be passed off as the growing pains of a nation, but almost thematically, killing each other over what we believe is the best for our country, has never abated. There is no better example of this than the American life of Robert Todd Lincoln, the slain president’s eldest son, which presents a thread that connects numerous historical tragedies. The only son of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln to survive into adulthood was present at three presidential assassinations, and they were not the only sorrows and heartbreak attendant to his life.

On April 14, 1865, Lincoln had been invited by his parents to attend the play, “My American Cousin,” but declined the offer, claiming he needed rest. The Harvard-trained lawyer had often publicly lamented that he’d had no more than ten minutes conversation with his father while he was serving as president, and that may have added more tears and emotional weight the next morning as he knelt crying by the bedside where his father had died. The president, of course, had taken a bullet to the head from Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln had led the nation through a great battle to save its union of states and end human slavery, an idea incomprehensible to most Southerners of influence.

Robert Lincoln had dropped out of law school while hoping to serve in the Army during the war. His mother refused to countenance his plans and compromised with the president that their son might serve on the staff of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, which put the young Lincoln at Appomattox Court House when the articles of surrender were signed by Robert E. Lee. What he must have seen even at the edges of the war’s great battlefields was a loss and sadness wrought of politics and compounded by his family’s tragedies. Edward Lincoln, Robert’s younger brother, died at age 4 from consumption, a name given to tuberculosis prior to proper diagnosis; sibling Willie Lincoln died from typhoid fever at age 12 while living in the White House, and the youngest Lincoln child, Thomas, known affectionately as Tad, passed at age 18 from an undisclosed illness.

Robert Lincoln had moved to Chicago with his widowed mother and his youngest brother to practice law before he was cajoled into returning to Washington by President James Garfield. He was serving as Secretary of War and meeting with Garfield as the president departed the train station in the national capitol city on July 2, 1881. Lincoln was only 40 feet distant when the president was gunned down by Charles Guiteau, just sixteen years after Robert’s father had been slain. Garfield passed 80 days after being shot from surgical complications. Contemplating the loss of his three brothers who were already deceased, his presidential father, and Garfield, Lincoln was quoted by a New York Times reporter as asking, “My god, how many hours of sorrow have I passed in this town?”

He was to accumulate more hours of sorrow, losing his own son, Abraham Lincoln II, to a post-operative infection at just 16 years of age. Robert, at that time, was serving President Benjamin Harrison in England as Minister to the Court of St. James. After returning to the States, Lincoln went to work for the Pullman Palace Car Company, a manufacturer of passenger cars for trains, and eventually became CEO. He was traveling with his wife from New Jersey to Chicago and decided to stop in Buffalo at the Pan-American Exposition, a type of World’s Fair promoting trade between North American countries. A messenger was waiting for the Lincoln’s with a telegram when the train arrived that said McKinley had been shot twice in the abdomen a few hours earlier at a public appearance in Buffalo and was in serious condition. Lincoln went immediately to the president’s bedside and was assured the would-be assassin, Leon Czolgosz, had failed to take down McKinley. Unfortunately, the president died seven days later, also of infection.

Lincoln, though, lived a long life and was present for the dedication of the memorial to his father on the Washington Mall in 1922, and died four years later just shy of his 83rd birthday. Almost exactly a century after the murder of his father in Ford Theater, another president was killed by the country he was serving. The assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy is still rending the garments of American politics because the facts of what happened are seemingly unknowable after botched investigations and misinformation, a process now borne digitally to voters with the express purpose of distorting their perceptions of reality. We are a nation that often seems to kill its best and brightest, or at least have found no way in our body politic to deploy effective means of prevention. Who knows what kind of country we might have become had JFK, RFK and MLK lived to inspire and guide our government and its policies? There is sufficient cause to wonder how the republic itself has survived.

Which may not happen if we fall again for the lies of 2016.