What's the Matter with Texas?

“The best argument against democracy is a five minute conversation with the average voter.” - Winston Churchill

The calls and emails keep coming in and people expect me to be able to answer the question: “What’s the matter with Texas?” I can’t. I suppose I should have some understanding of this place that I love. I have been writing and reporting on politics here since Jimmy Carter held a rally in McAllen’s Archer Park during his last campaign swing in 1976. I remember the crowd giggling a bit at the future president’s Spanish, but he was warmly and enthusiastically welcomed by the overwhelmingly Mexican American crowd.

The peanut farmer did not appear like the wealthy patrons of the border whose businesses and money and political influence controlled the lives and economics of local populations on the Rio Grande. When I had arrived from the North as a “guero” outlander, I was oblivious to the political infrastructure that had evolved to serve oppression. As Carter stood the stage in the warm tropical sun, the audience included hundreds of voters who still had memories of having to pay a tax just to get the right to vote. The poll tax had become law in the 1890s and was used as a technique to keep African Americans from voting until it was repealed by the 24th Amendment to the constitution in 1964, which meant it worked just as efficiently against other ethnic groups.

My second day on the job at the radio station in McAllen, my new employer wanted me to go out and do an audio profile on the mayor, a wealthy planter whose produce made him millions. The purpose had nothing to do with the news, of course, and was rather to curry favor with a man who exercised influence over other local companies and their interests in spending advertising money on our airwaves. They might also see themselves as potentially becoming the subject of a flattering profile on the radio and be more inclined to advertise and support the economics of the AM station.

The mayor was tall, angular, and awful. I restrained myself the best I could with my writing but there was very little to like about the man. We got into his Lincoln Continental Town Car and then drove up and down the canal levees and turn rows of his crops and watched as his minimum wage field hands swung hoes and picked vegetables in the one-hundred-degree heat. Occasionally, he stopped, rolled down his power window, and motioned for one of the laborers to come over to the car. When they approached, he lowered the window, but not enough that he might have to feel the great heat and humidity, and then remonstrated the worker in animated Spanish. I was not fluent but knew from the tone of his voice he was not issuing compliments. His employee always went away chastened.

The story I filed made no one happy, including myself. I should have been more direct about the mayor’s patrician attitude and his condescension to people whose back-breaking labor were making him wealthier by the hour. Instead, I played it down the middle like a nice, objective reporter, which did nothing to placate my new employer. I thought I had been sufficiently circumspect by not handing the mayor his testicles on the air for being such an irredeemable human being, but the bossman was angry. He wanted a radio hagiography so he could get slapped on the back at the next Chamber of Commerce cocktail hour. My journalism was dangerous to me, too, since I’d come down the continent with a new bride, no other family, and had been promised only $160 a week in pay. Termination in the first week would have likely put me out in the fields, too.

I learned a great deal about Texas and its treatment of ethnic minorities during our years on the border. In the Rio Grande Valley, tens of thousands of poor were living in colonias, un-zoned tracts of land that were sold in small chunks and on time by immoral developers chasing easy dollars. There were rarely sewers, electricity, or even water, and the vast Las Milpas colonia, an unincorporated settlement between Pharr and McAllen, suggested there was an American Third World. In fact, a national news magazine had pointed out that the Valley’s economic statistics in the mid-70s were worse than many developing nations and the publication trumpeted a front-page story that proclaimed the region had the highest incidence of intestinal parasites, most outdoor privies, lowest per capita income and education level, the worst rate of childbirth mortality, and lowest percentage of college degrees.

This, I discovered, was by design.

The patron system made it all possible and was a cultural artifact that kept a cheap labor supply available for working the farms in the sub-tropical region where the Rio Grande reaches the sea. Employers did not ask too many questions about your origins if you were willing to spend long hours bent over pulling up vegetable crops and staying quiet when the crop dusters passed over spraying chemicals that might alter the course of your life. The economic infrastructure was built around citrus, oranges, ruby red grapefruit, and row crops hauled to produce houses for shipment to northern markets. Disrupting that construct by offering a living wage was certain to also change the political dynamics and make immigrants and low-income employees believe they ought to have real influence. They never did, and even though Latinos represented more than 90 percent of the population, invariably, the political strata remained almost universally white for far too many decades.

When we moved north up the river to Laredo, I understood that form of oppression and corruption was a way of life. The political power brokers in Webb County, brown and white, skimmed millions from federal grants to benefit themselves and their businesses and not their community. Laredo, which still had 230 miles of unpaved streets inside the city limits during the 1970s, also managed to maintain a street department with more than 1000 employees. These were mostly “no-show” jobs that were offered as a reward to citizens who had previously presented their stacks of poll tax receipts and agreed all those votes would be provided for a designated candidate. Millions in federal tax money, which was meant for buses and street improvement, disappeared into various political and private accounts, the most notable belonging to the mayor, a man known as Pepe Martin. Ultimately, he was indicted for only mail fraud and spent a scant six months of weekends in jail for the enduring financial rape of his hometown. Laredo, I concluded as I sat on the steps of our single-wide mobile home and stared at Interstate traffic going north, was not much different than it had been in the days of the Old West.

When we came to Texas from Michigan in ’75, we had rolled through the darkness not far from Los Horcones, George Parr’s ranch, where he had been found dead by suicide a few months earlier. I was oblivious to the powerbroker Parr family, which came from back East and had reigned over six South Texas counties for decades, controlling jobs, taxes, and public offices. Rather than appear in a federal court in Corpus Christi for various charges of corruption, Parr drove to his brush country spread, parked his car, and placed a pistol against his temple. His power emanated from racial animus and intimidation of Mexican Americans through poll taxes and job patronage. There are unmarked graves in the brush country of Duval and Jim Well Counties of people who crossed Parr, and some have tombstones and are right in town. One of those is a reporter named Bill Mason.

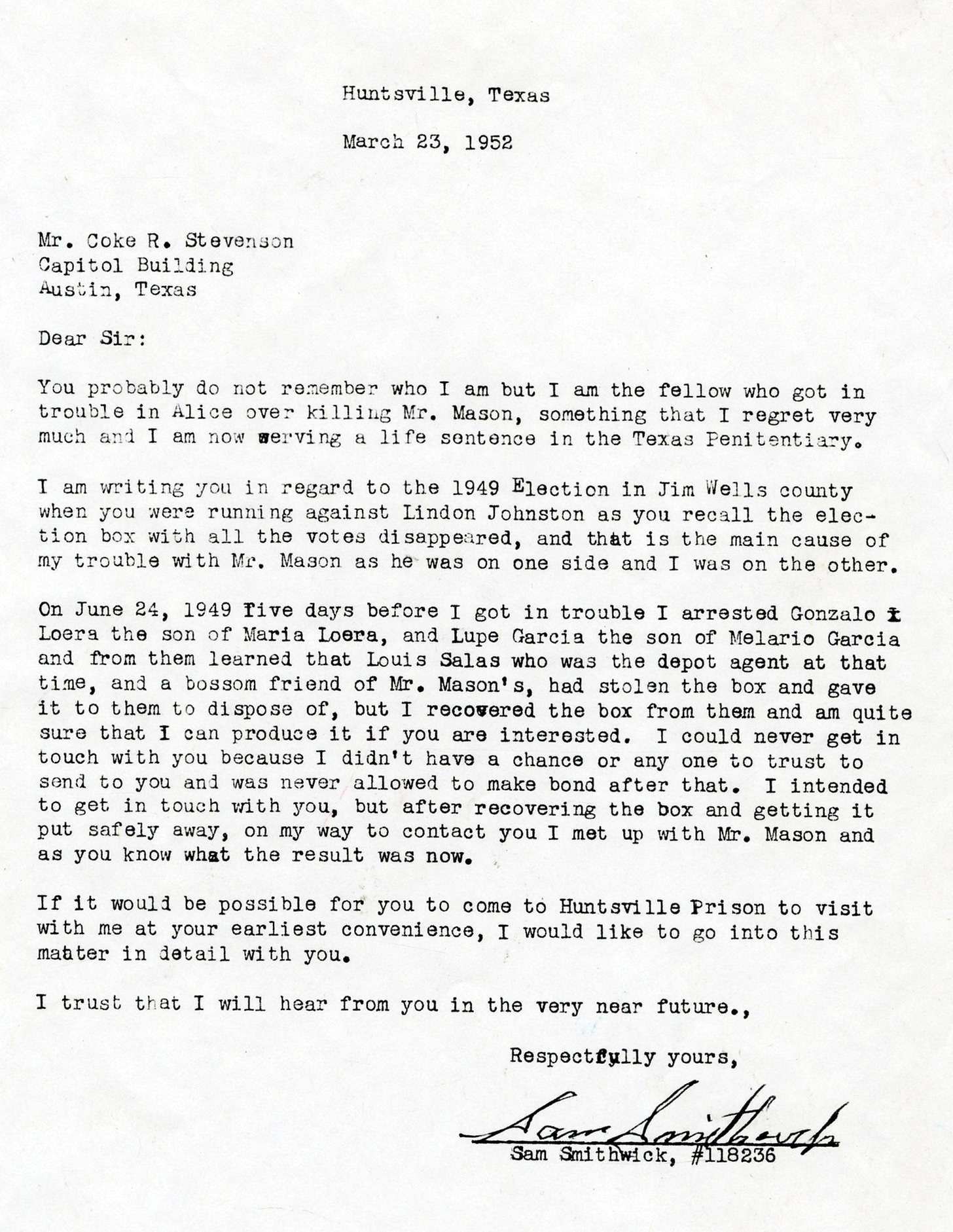

Without Parr, there almost certainly would have never been a President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Parr had his pistoleros stuff Box 13 and sign names to voter rolls to give LBJ a win in the Democratic Primary in 1948. Many of the signatures were from dead citizens of Duval County. When the new reporter Mason came to town, he did not have to search far to find signs of improprieties in Parr’s adjudication of Duval and Jim Wells County laws. Judge Parr had been slinging around kickbacks where he needed them and was providing his deputies with dance hall beer joints that were covers for whore houses.

The powerbroker certainly didn’t want the heat from Mason’s writings in the local paper and on his radio talk show, which is why he dispatched his illiterate deputy Sam Smithwick to take care of Mason. Within 48 hours, Mason was dead with a bullet through his heart, and Smithwick was soon off to Huntsville for life. Parr’s problems were solved until Smithwick wrote a letter to former Governor Coke Stevenson, who had been defeated by LBJ. The convicted killer of reporter Mason offered to blow the whistle on the Box 13 scandal but before Stevenson could get to the prison to interview him, the ex-cop was dead by hanging in his cell; ruled a suicide without investigation.

Although we are generations removed from the patriarchal politics of those days, there seems a whiff of history that informs the Latino vote in Texas. I admit it might be a bit too facile of an explanation for the persistent lack of enthusiasm by Latino voters in Texas, and other ethnicities, but distrust of the system is often a family legacy. Hispanics recently became the majority demographic in Texas but still do not wield proportionate political influence. An increasing number of Latino and Latina candidates has helped increase turnout, but the vote totals have not appeared to be sufficient to be considered decisive. Regardless of claims Republicans were going to make sweeping gains in Texas among Latinos, and especially along the border, Texas Democrats showed a four percent increase among Hispanic voters since 2020 and surrendered only one congressional seat in South Texas. Sixty-four percent of Mexican American voters cast their ballots for Democrats in Texas congressional races. They also identified the economy as their main concern, which was an issue Greg Abbott hammered and Beto O’Rourke spoke of infrequently.

I do not think it is difficult to understand Texas voters, though. In many respects, they don’t give a damn and completely lack trust in the process. I am not talking about MAGA distrust, the kind where there is doubt about votes being properly counted. The true cynicism comes from voting for change to happen, and then it never does. The promises rarely change each campaign season, only the names and faces are new. The guarantee, though, that property taxes will go down, teachers will get paid properly, roads will be paved, the environment will be protected, and the economy will grow jobs, is never kept. Not much of that ever happens, frankly, and year after year after year, fewer people show up to cast ballots even as the state’s population grows. If you want a prime example, look at the constitutional lawsuits over public education in Texas. The first one was filed in 1968, Rodriguez v. Board of Education, and the state is still getting sued for its failure to provide a constitutionally mandated equal education.

Turnout for this midterm election was, predictably, low. Only about 45 percent of the registered 17,672,000 voters bothered to show their face at the polls. County by county, the numbers were all down, even as analysts expected an increased turnout among ethnic voters and, especially, women, who were beleaguered by the legislature’s anti-abortion laws. The notion that people don’t vote because they are lazy is generally unfounded. The more palatable explanation is that they have come to believe their vote doesn’t matter, and that they are not obligated to make their voices heard when the government throws obstacles in their way to register and cast a ballot. Why bother when the president you were certain was peaceful leads the country to war under false pretenses or the governor who says he’s pro-life passes laws that take away women’s rights and put their lives in danger for getting pregnant? There is no state where this endemic institutional apathy is destroying democracy more virulently than it is in Texas.

What’s the logic? How did Greg Abbott win? Or did Beto O’Rourke lose? In his last campaign, the El Pasoan won every urban county over Ted Cruz, and, strategically, saw his future success in moving numbers in rural counties. O’Rourke took off for the country with his gubernatorial campaign and got big percentages of crowds in small communities. He talked about Abbott’s failure to expand Medicaid and how that caused two dozen rural hospitals to close and how the governor vetoed a billion-dollar measure that would have expanded broadband service to small town Texas. If a decent number of those voters would have moved in the Democrat’s direction, he might have had a chance, but they saw him as anti-gun after his comments following the Walmart massacre in El Paso, and Abbott had convinced rural voters O’Rourke was weak on the border. The candidate didn’t want open borders, but he never offered a solution to what is clearly an immigration problem. Instead, he criticized Abbott for being a xenophobe and using people for political props, which is true, but hardly mattered in the great out yonder.

Texas Democrats need viable candidates, leadership, infrastructure, and a vision that is articulated by strong messages. They have, frankly, none of the above. What they possess at this moment, is a pretty grim future under the lone star.