Women’s History Month: Inspiring Change from the Inside, Forcing Change from the Streets

There's a structure of organizational norms created by a ruling class with little regard for human rights, fairness, or equity. Long ago, these women did both to move the needle toward fair and equitable treatment.

Listen closely and you’ll hear the shattering sound of another woman cracking through a glass ceiling, but I wouldn’t break open the champagne just yet, the gains are respectable although not enough. The percentage of women in senior management roles grew globally to a record 32% in 2022, but women remain underrepresented in leadership positions. So, the fight for equal rights in business, politics, and the workplace must continue to be fought on two fronts; speaking up to change policies and practices from inside an organization, while confronting and bringing attention to systemic discrimination with protests, boycotts, and marches from the streets. Long ago, these women did both to move the needle toward fair and equitable treatment.

We called it “the system,” in the 60’s and 70’s. You could define it as the structure of organizational norms created by a ruling class with little regard for human rights, fairness, or equity. The system, left unchallenged, continues to grow as a bulky, offensive, bigoted cruise liner, skewed to preferred passengers and to create monopolies. The history books don’t always shine a light on the women who worked to better the system from within, or from a picket line—outside. Their courage and unique stories have contributed to Women’s History, which is American history.

Fighting for Change, Inside the System

Jeannette Pickering Rankin, first Woman Elected to Congress but she couldn’t open a bank account on her own. That wasn’t “allowed” until the 1960s.

Republican Representative Rankin was first elected to represent Montana voters in the U.S. Congress in 1916. She served one term and was elected again in 1940.

In 1941, Rankin was the only member of Congress to vote against declaring war on Japan, a vote so unpopular, she had to hide in a phonebooth to escape a crowd of angry reporters until Capitol Police could escort her to her office. Her comment at the time was, "As a woman I can't go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else." She was ridiculed by the press and received angry telegrams and phone calls from the public.

Progressive newspaper editor William Allen White praised Rankin’s courage. He wrote: “Probably a hundred men in Congress would have liked to do what she did. Not one of them had the courage to do it. The Gazette entirely disagrees with the wisdom of her position. But Lord, it was a brave thing! And its bravery someway discounted its folly. When, in a hundred years from now, courage, sheer courage based upon moral indignation is celebrated in this country, the name of Jeannette Rankin, who stood firm in folly for her faith, will be written in monumental bronze, not for what she did, but for the way she did it.”

Maria Adelina Isabel Otero-Warren

In 1922, Maria Adelina Isabel Otero-Warren became the first Latina to run for Congress. She vied for a seat to represent New Mexico. Otero-Warren was part of what was considered the Hispanic elite, her father had migrated from Spain.

In 1883, two-year-old Otero-Warren lost her father in a fight with white men who questioned his property ownership. Her mother got remarried to an English businessman. She was an activist for social and educational developments, who focused on the importance of education, and improving local schools.

Otero-Warren was influenced by her mother. She became a suffragist and the first Mexican-American state leader of the Congressional Union in New Mexico, with support from both the Spanish- and English-speaking communities.

Otero-Warren was an advocate for Hispanics in improved education, health care, and welfare services. Her promotion of Spanish-language instruction in public schools was considered controversial at the time. That position coupled with news of her divorce led to defeat in the congressional race.

Anna Sutherland Bissell

The first woman CEO in the United States, a teacher and joint partner in the business, stepped into the CEO role when her husband, Melville Bissell died. He invented the Bissell carpet sweeper in 1876.

As CEO Anna Bissell moved the company into international markets and established new guidelines on trademarks and patents. By1899, she had created the largest organization of its kind in the world.

Muriel Faye Siebert

Muriel Faye Siebert was the first American businesswoman to own a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, and the first woman to head one of the NYSE's member firms. But it didn’t come easy.

Siebert worked at several brokerages before establishing her firm, Muriel Siebert & Co., Inc. in 1967. The firm performed research for institutions, buying and selling financial analysis. When Siebert asked investors to sponsor her application for a seat on the NYSE, nine out of ten refused. And the NYSE used a “new” catch 22-rule that required her to obtain a letter from a bank offering loans of $300,000 at the near-record $445,000 seat price. The banks refused until the NYSE would agree to admit her. Siebert was finally elected to membership on December 28, 1967.

In 1977, she was named Superintendent of Banks for the State of New York, with oversight of all of the state’s banks, regulating $500 billion. Not one bank failed during her tenure, despite nationwide bank failures.

Mayor Kathy Whitmire

In the 1990s, Houston’s first woman mayor and my former boss was elected to the board of the New York Stock Exchange after leaving office. Mayor Kathy Whitmire remains one of the most successful former mayors of Houston. She served as Director of the Rice Institute for Policy Analysis and held the Tsanoff Lectureship in Public Affairs. At Harvard University she was a lecturer on Public Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government and a Fellow at Harvard's Institute of Politics. She later joined the Academy of Leadership at the University of Maryland. As a fiscal conservative and social liberal, Whitmire advanced a pro-business agenda and stood strong against opposition for the inclusion of women and minorities in city business contracts during her five terms as mayor.

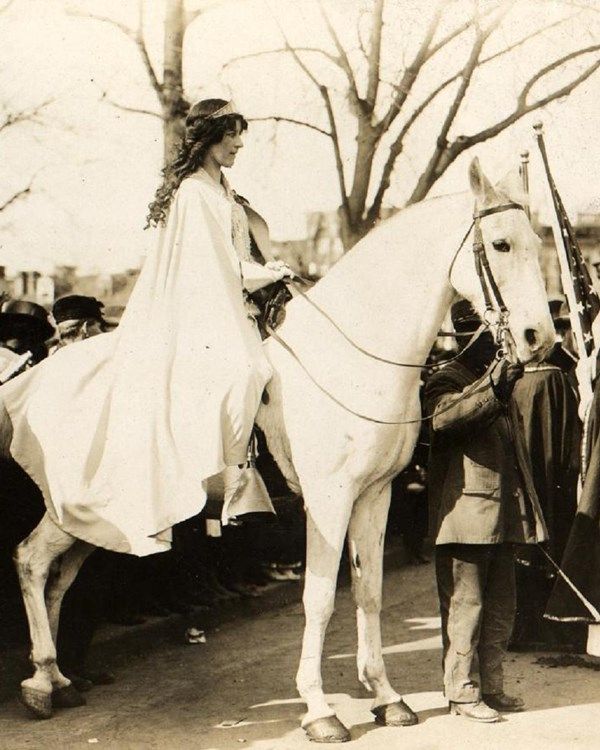

Taking it to the Street - Inez Milholland Boissevain

In 1913, Inez Milholland Boissevain upstaged the Inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson by leading the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C. riding horseback in a flowing white cloak wearing a crown. Boissevain was a labor lawyer and war correspondent, who lived an avant-garde lifestyle. She seemed to be well ahead of her times.

Rose Schneiderman

And while this group of women might be considered politically incorrect by animal rights activists today, they made headlines in 1909 as The Mink Brigade. The wealthy women from prominent families sympathized with New York garment workers in their protest for fair wages and safe working conditions. Most of the workers were immigrant women who were attacked and arrested by police during their strike, known as the Uprising of 20,000. Police didn’t attack the wealthy women, of course. Leader of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), Rose Schneiderman wrote, the Mink Brigade "lent prestige and, more important, an aura of respectability to our demonstrations. This was most important for it helped to weaken the attempts of the unsympathetic to force the women back to work through prison sentences and physical violence."

The Mink Brigade made an impact, but it wasn’t enough. In 1911, 146 workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory died in a fire at the factory. The workers were trapped because managers had locked the doors to stairwells to bar workers from unauthorized breaks. Some of the victims were as young as 14 years old.

Sue Ko Lee

Twenty years later, a similar garment workers battle was joined by Chinese American women in San Francisco.

When white-owned companies refused to hire Sue Ko Lee she found work with National Dollar Stores which was founded by Chinese-Americans. Sadly, the pay was low and working conditions below standards—what we would call, sweatshop conditions.

In 1938, Lee and her co-workers voted to join the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, (ILGWU) and using ballots written in English and Chinese, they formed the Chinese Ladies’ Garment Workers Union Local 341. It was the first time Chinese women fought poor working conditions in the garment industry---they maintained a four month work stoppage.

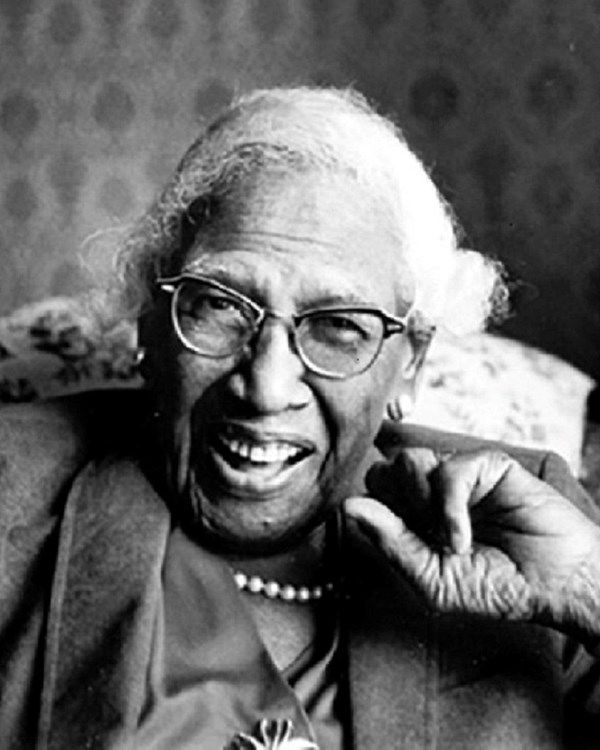

Rosina Tucker

It’s unlikely that school history books tell the story of Rosina Tucker, but if not, they should. Her work benefited the mostly African American train porters during a time when train travel was king in the U.S.

Tucker was born in Washington, D.C. to formerly enslaved parents in 1881. Her father taught himself to read and write and worked as a shoemaker.

Members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters needed fair pay and better working conditions, but because they worked long hours and felt their jobs would be threatened, they didn’t attend organizing meetings. Tucker and other porter’s wives held secret meetings for them.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was founded in 1925 as the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor, (AFL). They attracted a membership of 18,000 from the U.S. Canada and Mexico. On behalf of the union, Tucker visited hundreds of porters at their homes, distributing literature, recruiting members, and collecting dues. When the Pullman Company learned of her union activities, they retaliated by firing her husband. She confronted his supervisor. She said,” I looked him right in the eye and banged on his desk and told him I was not employed by the Pullman company and that my husband had nothing to do with any activity I was engaged in ...I want you to take care of this situation or I will be back.” She added, “He must have been afraid ... because a black woman didn't speak to a white man in this manner. My husband was put back on his run.”

Tucker continued her work on behalf of unions and became an important figure in the civil rights and women’s rights movements. In her later years she helped organize laundry workers, and airport red caps, and testified before House and Senate committees on daycare, education, labor, and D.C. voting rights.

The need to guard and protect the rights of women, people of color, the disabled and any marginalized group, is like a broken record of narrow-mindedness in America’s history. Women leaders today have had the benefit of a path carved long before them by thousands of brave women. It is unfortunate and ridiculous that so many of their stories have been left “on the cutting room floor” of American history books.