Zen and the Art of Remaining Upright

When I had first encountered Robert M. Pirsig’s book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values... I kept rereading through the years and grew to appreciate its subtle teachings. “The real cycle you’re working on,” he wrote, “is a cycle called ‘yourself.’

“I have ridden a 500-pound Vincent through traffic on the Ventura Freeway with burning oil on my legs and run the Kawa 750 Triple through Beverly Hills at night with a head full of acid. I have ridden with Sonny Barger and smoked weed in biker bars with Jack Nicholson, Grace Slick, Ron Zigler, and my infamous old friend Ken Kesey, a legendary Cafe Racer. Some people will tell you that slow is good-and it may be, on some days-but I am here to tell you that fast is better. I’ve always believed this, in spite of the trouble its caused me. Being shot out of a cannon will always be better than squeezed out of a tube. That is why God made fast motorcycles, Bubba.”

- Hunter S. Thompson, “Song of the Sausage Creature,” Cycle World; March, 1995

The sandlot where we played baseball as kids had a brick building that was located relatively deep in right-center field. Water pumps that supplied the circle of houses in our neighborhood were within those walls, and consequently, we named our little diamond “Pump House Park.” A ball hit to the roof of the pump house was considered a home run.

The home run barrier in left field was a shallow ditch that ran parallel to a gravel road, which was slightly elevated from the outfield. The ditch was more like a scooped-out trench to drain water after heavy rains, but it was mostly dry. There was nothing I liked more than chasing a fly ball back toward that culvert before leaping into the air to steal a homer as I fell onto the gravel of Reid Road, ball still secured in my glove.

Our pickup game was delayed one summer day when I was eleven years old by a motorcyclist riding back and forth across the outfield ditch. I do not recall the type of motorcycle he was riding but it was big and loud without saddlebags or a windshield. As he approached the ditch from the outfield he accelerated just slightly and then popped his clutch when the front wheel rolled across the brief upslope. The effect was to launch his motorcycle into the air three or four feet before landing on the other side of the road.

A few of us, including me, put down our baseball gloves to go out and watch. I was worried his tires were digging up the outfield and that the ball might no longer bounce true, but this was the first time I had been close to a motorcycle. The rider, who lived in a house on the other side of Reid Road across from our sandlot, spun his tires in the gravel and pulled into his driveway. His friends were sitting in lawn chairs watching him perform and they handed him a beer that he drank with one tilt of his head before spinning his rear wheel and turning the bike back toward us.

I wanted to ask him if he would quit so we could play baseball but as he approached the ditch again, I saw his fierce face and sunburnt skin and doubted the wisdom of my impulses. We watched as his bike dipped down into the depression but this time, he popped the clutch too late, and the back wheel caught the power acceleration on the upside of the ditch and threw the rear of the motorcycle into the air while the front tire stayed on the road. The rider was tossed over the handlebars and landed sideways on his neck as the motorcycle crashed down within inches of his head.

We stared, not knowing what to do, and his friends, who had been watching from his front yard, ran to provide help. I walked over as they had gathered, and a woman, who must have been his wife started screaming, “Someone go call an ambulance. He’s hurt. He’s hurt bad.” I saw his eyes were open and he recognized her and started talking without moving.

“Where are the kids, honey?”

“They’re in the house. Watching cartoons. Don’t worry about them. An ambulance will be here in a minute. You’ll be fine.”

“No. No, I won’t. Will you get the kids over here? I wanna tell ‘em I love ‘em.”

“They know you love them. Now stop it.”

“Baby, I’m going away. I’m telling you. I know it. I wanna see my kids.”

“Oh, dear god. Please.”

She stood up and screamed at another woman standing in the doorway of her house and told her to bring the little boy and girl to where their father lay. I eased away with two of my friends, aware even at that age we were imposing on a personal tragedy, but we saw the two little ones lean over and kiss their daddy on the forehead as if he were already gone. Presently, his wife stood up and screamed and the children ran home. The men who climbed out of the ambulance after it arrived did not appear to be hurrying to administer aid and after they checked on the rider, they pulled out a gurney, lowered it and lifted his body onboard before covering him with a white sheet.

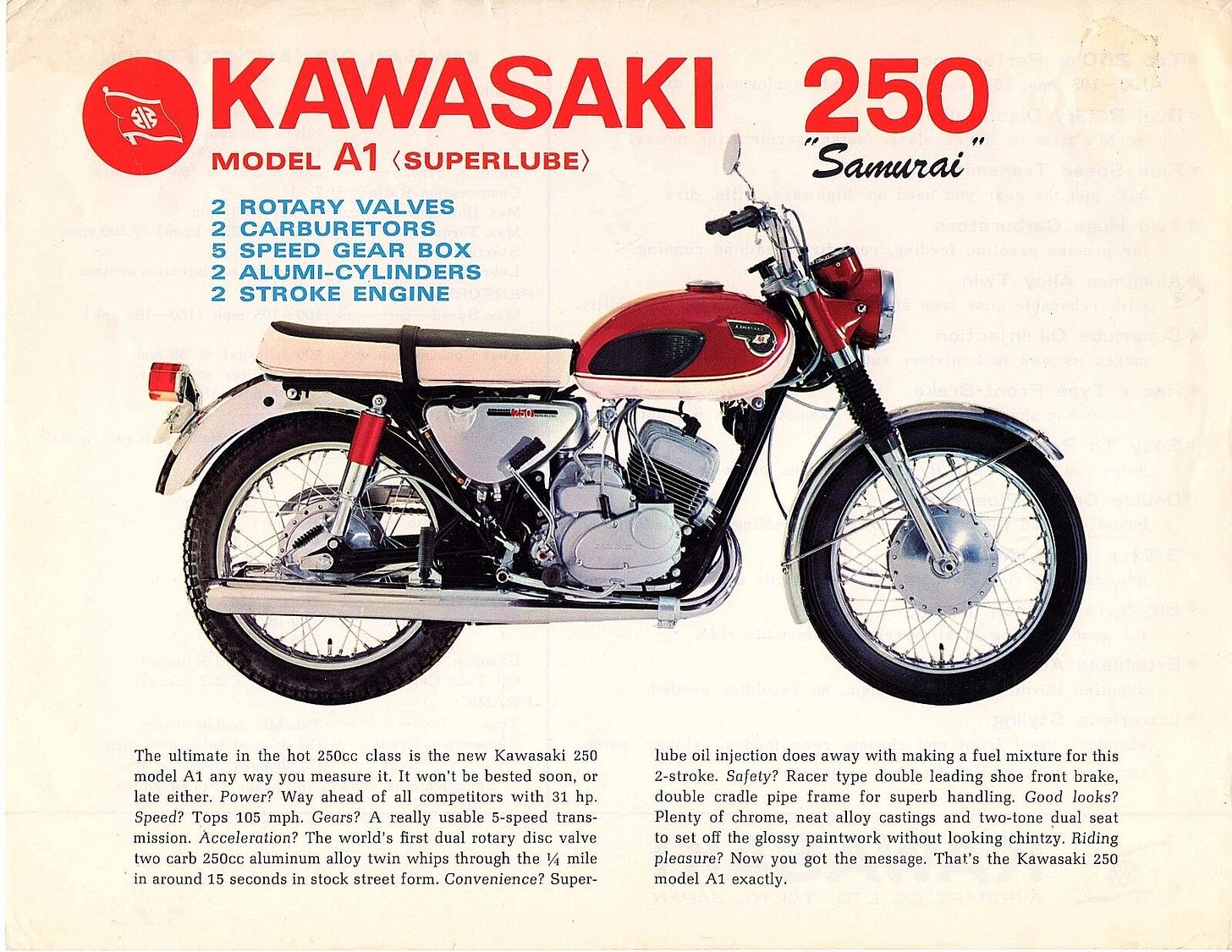

I had never seen a person die and the accident stayed with me every time I went to the outfield to shag fly balls. Maybe I should have been frightened, too, of motorcycles, but I was drawn to the machines, wanting to ride and feel the wind in my face. In high school, my brother and I pooled our caddy money one year and bought a used Kawasaki 250, a bike too fast for beginners. We rode, though, and learned to manage the clutch and throttle and foot brake and were unafraid until Tim crashed into a tree while riding dirt trails. The tank on that bike was slightly raised and he was thrown forward, smashing his crotch against the gas tank, and after hospitalization, he spent a week in bed waiting for the swelling to go down from all the crushed blood veins in his genitals. He appeared to lose his enthusiasm for motorcycling.

I rode on, though. I was hooked on the sense of freedom and independence I felt on a motorcycle, as if I could ride away to any future I dreamed and all I needed was money for gas. I loved the smell of the world and the feel of the wind rushing over me and the delusion I was almost flying. In college, I used my $1.75 an hour wages working in the dormitory cafeteria to finance a Honda 450, and just as I began to ride with even greater confidence, I learned one of my high school track teammates had been killed in a head-on collision with truck up in the north woods. I remained unafraid, but not oblivious.

When my buddy Butch got home from Vietnam, he bought a Triumph 650 Bonneville, and we took off together to see as much of America as possible during my summer vacation from college. The Sunoco oil company was sending credit cards, unsolicited, to college students, and when one showed up in my mailbox at the dormitory, I decided I would use it for gas on the big trip and figure out how to pay it off after I graduated.

Butch and I rode west, up across the Rockies and down into Utah and then up the Great Basin where the entire world appeared to present itself as a singular tapestry of desert and sky. We did not spend a minute east of the Mississippi and chased after western sunsets and roads that twisted through national forests and climbed the Sierras. We ran down the Pacific Coast Highway and slept on the beach and came back across the Mojave in the night, which felt like we were stuck in the darkness of the universe and moving too slowly toward distant stars. There is a thing inexpressible about being young and fit and rolling across the face of the earth on a motorcycle without a destination.

When the little red-haired girl and I lived among the orange groves down along the border shortly after being married, I bought a used yellow Honda 750 café racer, which I could not afford. In the mornings, when I arose in the dark to sign on the radio station, I rode the Honda down the streets lined with palm trees and thought there might be no better place to live than a locale where you might motorcycle in year round warmth and the smell of orange blossoms filled the air. Whatever there was about bikes that I could not readily explain translated into my soul as a kind of liberating joy.

My only bad experience with a motorcycle at that time had occurred when I received my induction notice to the U.S. Army. I had drawn a very low number in the draft lottery, which meant when I graduated and my student deferment ran out, I was to be inducted into service. I had filed for a conscientious objector status after having been active in the anti-war movement even in high school, but my draft board kept refusing to hear my plea. The Army sent a bus down I-75 through the middle of Michigan to pick up all inductees to take them for physicals in Detroit. I skipped my first two notices and received a registered letter at the dormitory that if I did not present myself on the third date, I was to be arrested.

I got the message but refused to get on the Army’s bus and rode my Honda 450 to downtown Detroit to find the induction center and undergo my physical to make sure I was healthy enough to go overseas and get shot. I was on the inside lane of Gratiot Avenue when I spotted the Selective Service building off to my right and turned impulsively across the other lane and was struck by an old Buick Dyna Flo. The curved hood caught my hip and tossed me into the air over a fence and onto an asphalt basketball court. EMTs, who were driving past and witnessed the accident, came to my assistance by cutting both legs of my blue jeans up to the hip to reveal any wounds. There were none.

The Honda was still functional, but my jeans were not, and I rode back north with them flapping in the wind while wondering if the Army would believe my story. When I got home, my mother informed me the FBI had called and she wondered why I had missed my exam. I showed her the motorcycle with the bent handlebars and dented tank, and she asked again why I had to ride. To keep from being arrested, I had to call the local FBI office, explain what had happened, and then get sworn affidavits from Detroit’s EMTs and police. I turned in the paperwork a few weeks before the beginning of the Paris Peace Talks, which ended the draft and the FBI’s further interest in my character.

When we moved to Omaha, I bought my first Harley and traded in the yellow café racer. The new bike was a beauty, black and orange with laced wheels and an 883 cubic inch engine, which felt monstrous to me. Harley had put out the bike as a commemorative edition to celebrate buying the company back from the AMF Corporation, which had manufactured motorcycles so poorly the family brand was being harmed. I managed to buy the first “Milwaukee” model Sportster delivered to the Omaha dealership, which, like every Harley shop in the country, was to get only two of the limited production. I think it was the first time I had ever felt pride of ownership. My interest was never in owning things, even when I was young, but in how they might help me enjoy living. Nothing ever did that quite as effectively as a motorcycle.

We had both been busy working and the little red-haired girl had asked me if she was ever going to get to go for a ride on the new Sportster. We packed a picnic lunch and took off for the Military Highway, the quickest route to the rolling countryside north of Omaha. As we entered a curve where a median divided the road, I caught a glimpse of what looked like an oil spill, and just as I leaned to turn, the bike’s wheels slid out from beneath us and up against the curb. We were doing maybe 50 miles per hour but we both went airborne. She slid across the oncoming two lanes and smashed her hip into a curb while I flew past where she lay, the bike appearing to hover above me. I landed uninjured in the grass next to a sidewalk while the Sportster, carrying more inertia, nearly twisted in two and came to rest, totaled, against a fence.

My insurance claim was filed immediately, and I called the Harley shop to tell him I wanted to buy his second Milwaukee. He said other buyers had expressed interest, but no one had made a deposit and if I came in the door with a check, the bike was mine. Thrown from my horse, I got back on and took a week to make a solo recovery ride down to Arizona on my new Milwaukee. I rode through the Ponderosas of the Mogollon Rim south of Winslow and felt the warm desert air rise from the Salt River Valley into the piney woods. I stopped at almost every switchback the road made that afforded a view of the distant desert floor and a few times found myself emotionally overwhelmed with the bliss of my insignificance.

The rides of my life have comprised a personal dreamscape. A few years ago, I raced north with my buddy Gary in a non-stop 100-degree-plus day from Austin to Nebraska to experience our first total eclipse. We found people gathered at a convenience store near Hebron as they waited for the noonday sun to be blocked out and create a few minutes of night. Families had set up lawn chairs and were picnicking next to the tall stands of summer corn and when the light went out and crickets began to chirp, three minutes of respectful silence fell across the land. The sun seemed a greater force after the moon had transited its face and left us feeling almost punch drunk by the speed with which the phenomenon had expired.

Not only is there much to be experienced with motorcycles, there is even more to learn. When I had first encountered Robert M. Pirsig’s book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values, I thought it a fanciful merger of a narrative journal and obscure philosophical intent, but I kept rereading through the years and grew to appreciate its subtle teachings. Pirsig, too, was an example of the value of persistence. His manuscript had been rejected by 121 publishing houses before acceptance. When finally in print, the book became an immediate bestseller and has sold more than five million copies worldwide since its release in 1974, and it has never been out of print.

The appeal of his teachings still resonates in an increasingly technological time. Even with the simplicity of a two-cylinder engine, Pirsig insisted there was value in understanding the mechanics and providing care for it with proper maintenance. These practices, he was suggesting, were just as critical to the human doing the work as they were the machine. Pirsig’s purpose was to convince people they could lead a good and meaningful life by becoming one with whatever was their activity, engage in the minute details to appreciate fully being alive and undertaking a task. This, to him, was almost an expression of religion manifest in a machine.

“The Buddha, the godhead, sits quite as comfortably in the circuits of a digital transmission as in the petals of a lotus.” - Pirsig

“The real cycle you’re working on,” he wrote, “is a cycle called ‘yourself.’ The study of the art of motorcycle maintenance is really a miniature study of the art of rationality itself. Working on a motorcycle, working well, caring, is to become part of a process, to achieve an inner peace of mind. The motorcycle is primarily a mental phenomenon.”

I was prompted to reread Pirsig’s book, yet again, a few years ago after a turkey rose in front of me as I was riding at 70 miles per hour down a West Texas road. I needed a bit of Zen to get through the crisis of rebuilding a motorcycle. I was, predictably, talking politics on the headset with Gary as we headed homeward after a four-day cruise around the Texas Trans Pecos. Amid a sentence, Gary screamed, “Turkey!” I never saw the poor creature, but my windshield exploded into thousands of plexiglass chips; both mirrors and turn signals were torn off; the dashboard instruments destroyed; and the fairing was busted. There was also a large load of turkey shit across the front of my jacket.

My response had been proper. I did not panic and slam on the brakes and instead coasted to a stop in the breakdown lane. After slowing my heartbeat and regaining some composure, Gary and I resumed a long, much slower ride home, which was over twelve hours to get the crippled motorcycle back to my garage. Because the insurance company required costly original BMW parts for the bike, their cumulative value quickly exceeded the cost of the BMW, and it was considered totaled. I began buying parts with the settlement check and waited daily for delivered packages. I had never rebuilt a motorcycle, but YouTube, determination, and Robert M. Pirsig got me through the task. The BMW K1200 LT is still on the road and rides like a dream.

I would like to provide an understanding of a love of motorcycling and what happens to connect the rider with the machine in an almost transcendent meld, but I cannot. I do not have the literary skills or the philosophical bent of Pirsig. I only know that I feel different speeding along a smooth road under a clear sky, running to destinations known and unknown.

And I will never stop.